The Inevitable, Intergalactic Awkwardness of Time Capsules

A close examination of the Voyager Golden Records reveals the one flaw behind all attempts to bottle history: humans.

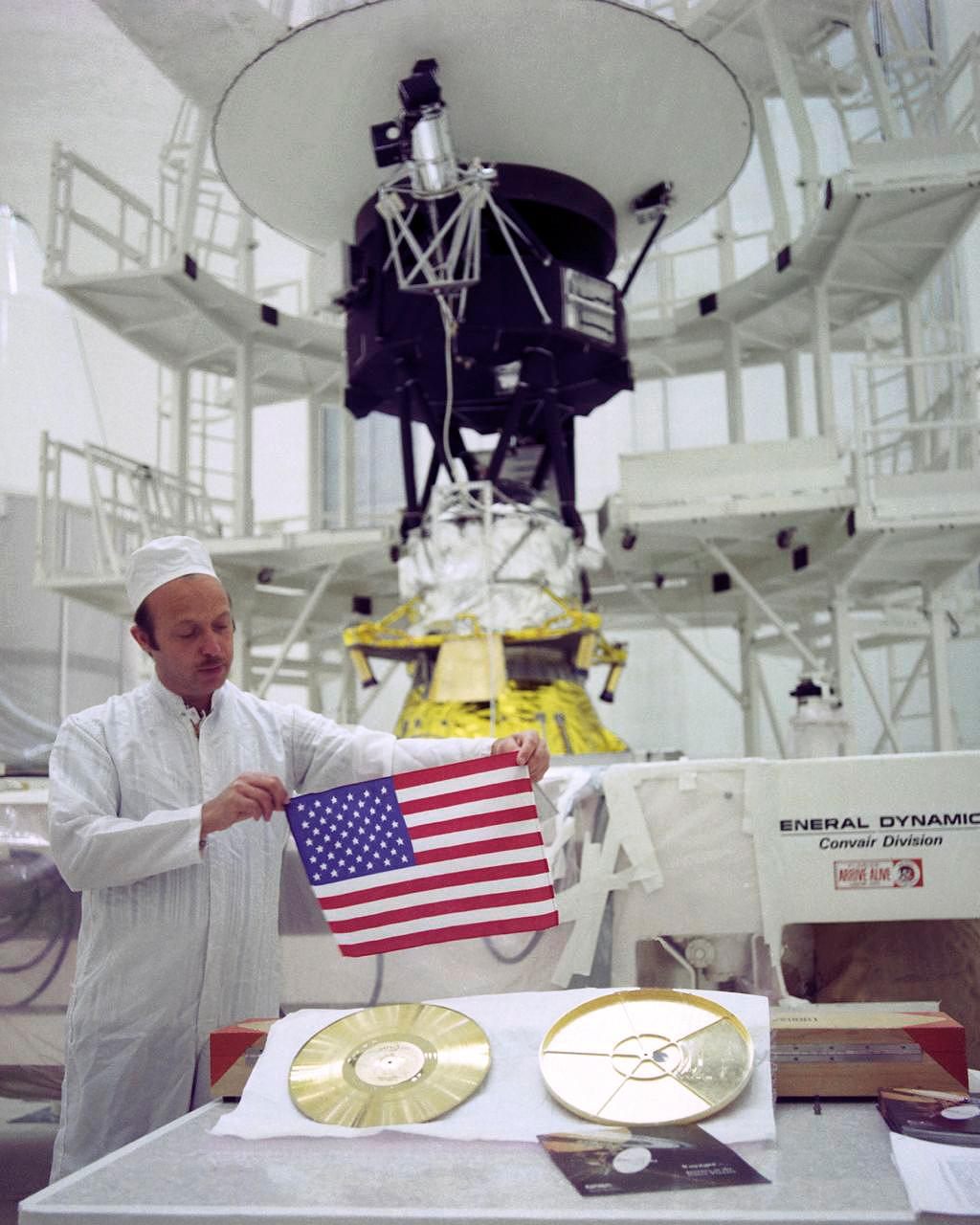

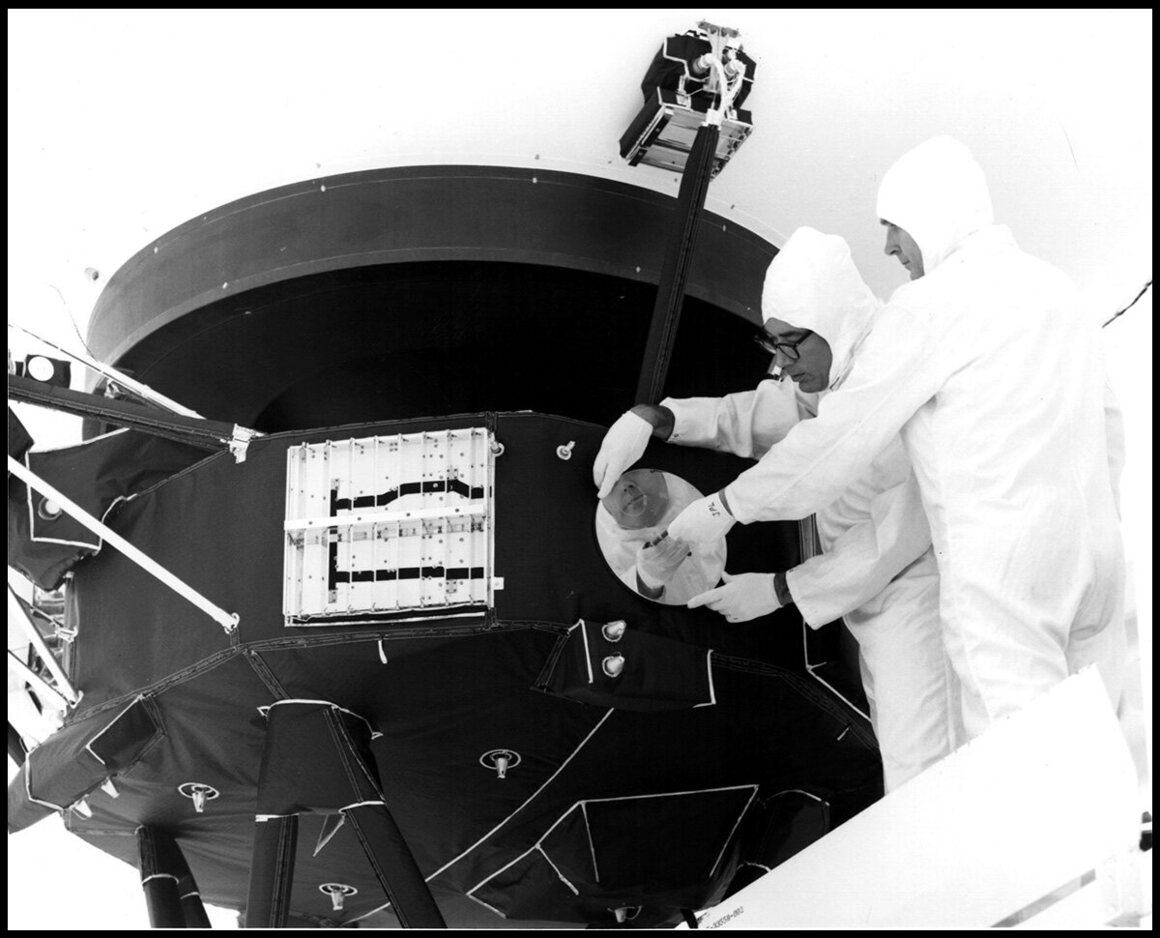

The Golden Record is affixed to the Voyager 1 spacecraft, 29 July 1979. (Photo: NASA/Public Domain)

The year is… let’s say it’s 42026. You’re cruising along your regular orbit, minding your own business, when suddenly, your craft’s detection system registers a mysterious interloper. An image of it blinks onscreen: It’s unshielded, it’s oddly shaped, and it’s not showing up in any of the databases.

From a distance, it looks like one for the junk heap—cheap metal, outdated design, and judging from its 17,000 meter-per-second approach, slower than anything else in the galaxy. But as it comes closer, something catches your attention. Attached to the underside of the craft, standing out against its black exterior, is a shiny disc.

Minutes later, you’ve towed the thing to the nearest port, and are watching as mechanics wrench the disc off, read the instructions, and begin to decode what’s inside. Someone in the know clues you in: you’ve found one of the famed Voyager Golden Records, the last known vestiges of the legendary Humans of the late Planet Earth.

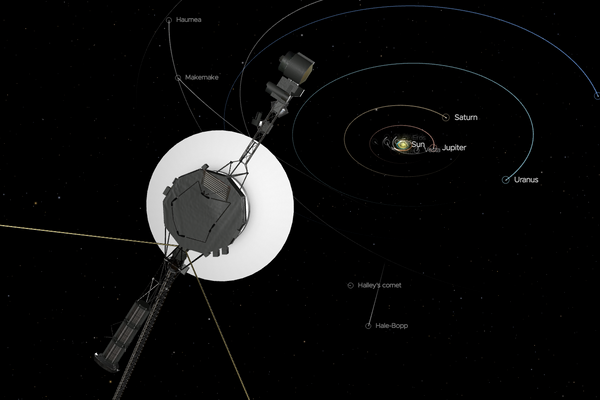

Launched in 1977 aboard Voyager Probes 1 and 2, the two identical Golden Records are essentially “Now! That’s What I Call Earth,” meant to sum up the whole warp and weft of humankind in 118 images, fifteen minutes of recorded sound, and a few dozen songs. The probes’ scientific instruments are slowly grinding down—by 2035, they will have all winked out—but the crafts themselves will keep going indefinitely, their shining cultural payloads in tow, prepared to show humanity’s good side to any aliens who might come across them. Jimmy Carter, the sitting U.S. president when they were sent off, described the records as “a present from a small distant world.”

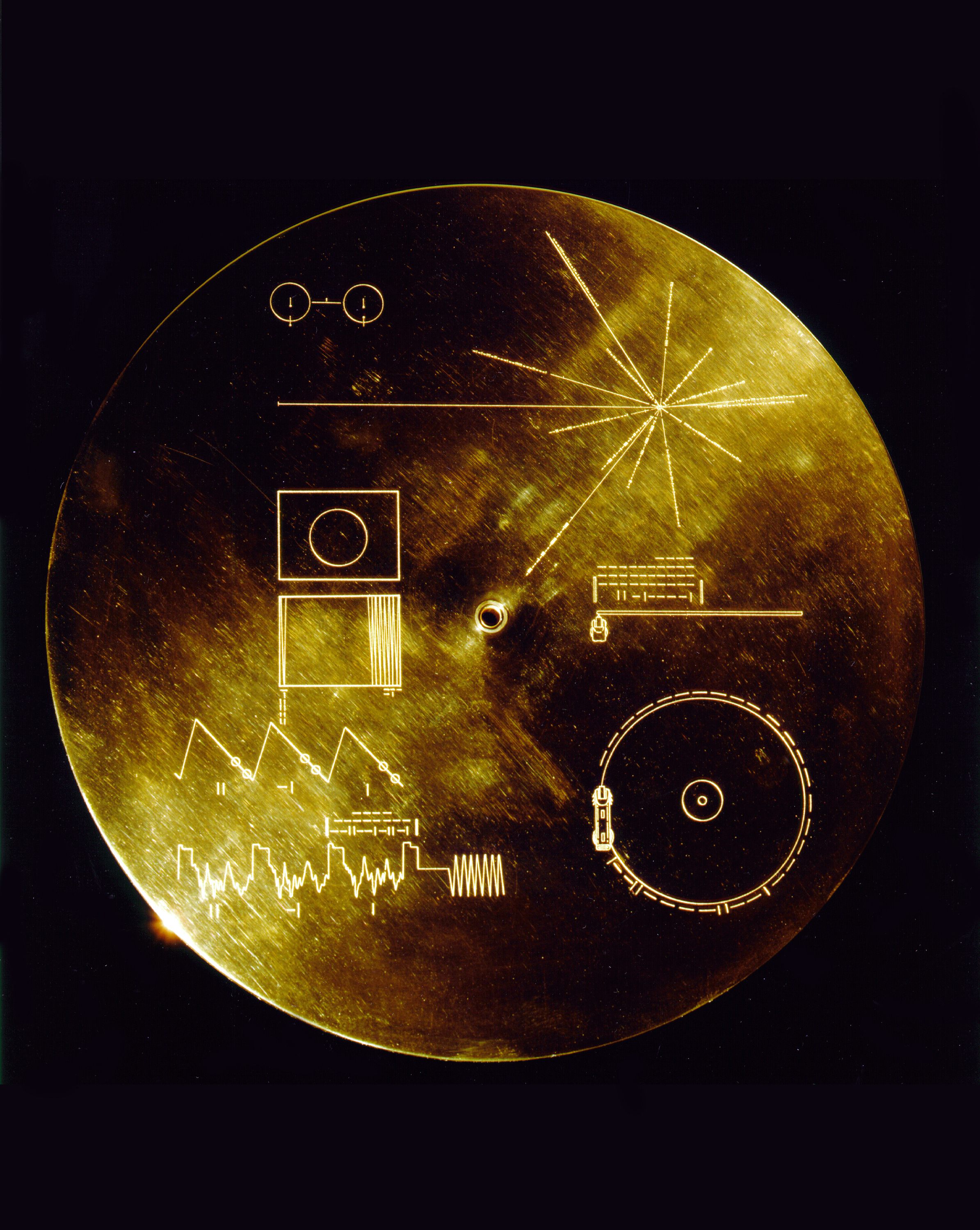

The cover of the Golden Record. The etchings are on both the inside and the outside, to account for erosion, and they have a specific meaning. (Photo: NASA/Public Domain)

Excited, you settle in to see what they’ve sent. Sound fills the room: moaning whales; stones slamming into one another; about a minute of strange crackling; an excellent trumpet solo. Pictures flicker across the walls: two human figures with all their anatomical details alarmingly censored by silhouette; a long list of names of 1977 US Senators; a balding man taking a bite out of a sandwich that already has a bite taken out of it on the other side.

“Zoinks,” you think to yourself, shaking your heads. “It’s no wonder these guys died out.”

Brag to the Future

Throughout human history, people have struggled with two competing impulses: the desire to make a mark for future generations, and a deep confusion about what, exactly, that mark should be.

The Golden Records, though probably the most extreme manifestation of this impulse, are far from the first. “There have been time-capsule type experiences ever since humans have measured time,” writes librarian William Jarvis in Time Capsules: A Cultural History.

It’s easy to make fun of time capsules, but, as Jarvis details, it’s much harder to fill them with the kind of material that will actually stand the test of time. Often, the things we tuck away for posterity are embarrassing or boring. Sometimes, they’re much worse—racist, bigoted, wrongheaded. Most take that old adage about the winners writing history to its logical conclusion. And they are always, by their very nature, exceedingly presumptuous.

The Voyager 2 launch on August 20, 1977, from Cape Canaveral, Florida. (Photo: NASA)

In the seventh century B.C.E., Esarhaddon, leader of what was then Assyria, took a deep breath and ordered his mind. As king, he had defeated enemy uprisings and extended his empire’s territory. He had built monuments and statues, and restored old, crumbling temples to their former glory. Now, it was time to complete another kind of royal task.

As his scribe stood nearby, stylus poised above a clay cylinder, Esarhaddon spoke proudly of his wide-ranging accomplishments. Dutifully, the scribe wrote them down. The cylinder, once dried, would be hidden in the walls of the city’s next building, to be found and studied by future kings—just as Esarhaddon, while remaking Babylon, had found and learned from his predecessors’ inscriptions. These carved monoliths—half historical artifact, half intergenerational chest-puff—are among the first time capsules.

When faced with incomprehensible vastness, humans generally respond by asserting ourselves. Religion inspires buildings and empires. Love leads to paintings, poems and songs. Even Mount Everest gets graffitied. Time capsules allow for a special kind of expression—they let us brag to the future.

“One of the functions of time capsules is glorified advertisement or boasting,” says Jarvis. To ensure their brag sheets’ longevity, the Assyrian kings ended messages by asking future finders to hype up their accomplishments, like an old-school reblog request. Many courted populist cred: In what Jarvis describes as an early PR move, Mesopotamian time capsules found hidden in walls specifically mention the high wages of the wall-builders. Esharhaddon’s successor, Ashurbanipal, wrote in one of his missives that his subjects were so excited about the whole thing, they threw their amulets en masse into the capsule’s burial site. (How he managed to include this information without time-traveling himself remains a mystery.)

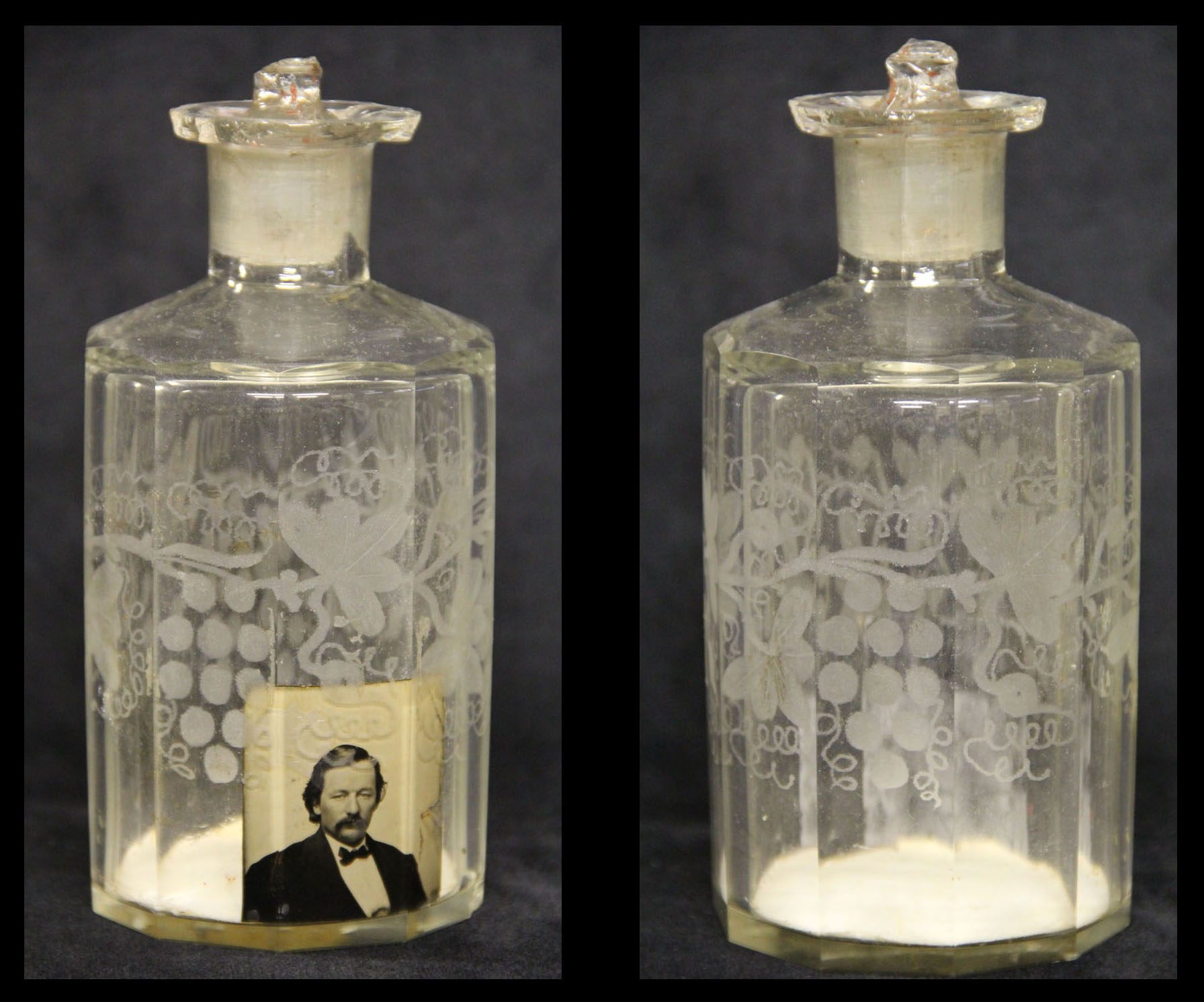

The wine decanter featuring a portrait of John McNulta, from his time capsule. (Photo: McLean County Museum of History)

The Golden Records (and their 1972 predecessors, the Pioneer plaques) were the first to explicitly market themselves toward aliens—although their creators were well aware that, with the low odds of the Voyager probes ever getting intercepted, Earthlings were their primary audience. But even as the intended audiences shift, the capsules’ psychological underpinnings stay pretty much the same. In 1879, an Illinois veteran named Lieutenant Colonel John McNulta put together a bottle of important items and bid that it remain sealed for a full century. McNulta had served in the Civil War, and experienced 14 years of its aftermath—Reconstruction, the Great Chicago Fire, the invention of the telegraph. When the McLean County Museum uncorked the bottle in 1979, as instructed, they were treated to the items McNulta had considered worth saving: a picture of himself, the menu for a fancy banquet he’d been to, and an unsmoked cigar, which McNulta ordered be enjoyed by either one of his descendants or a particularly good soldier.

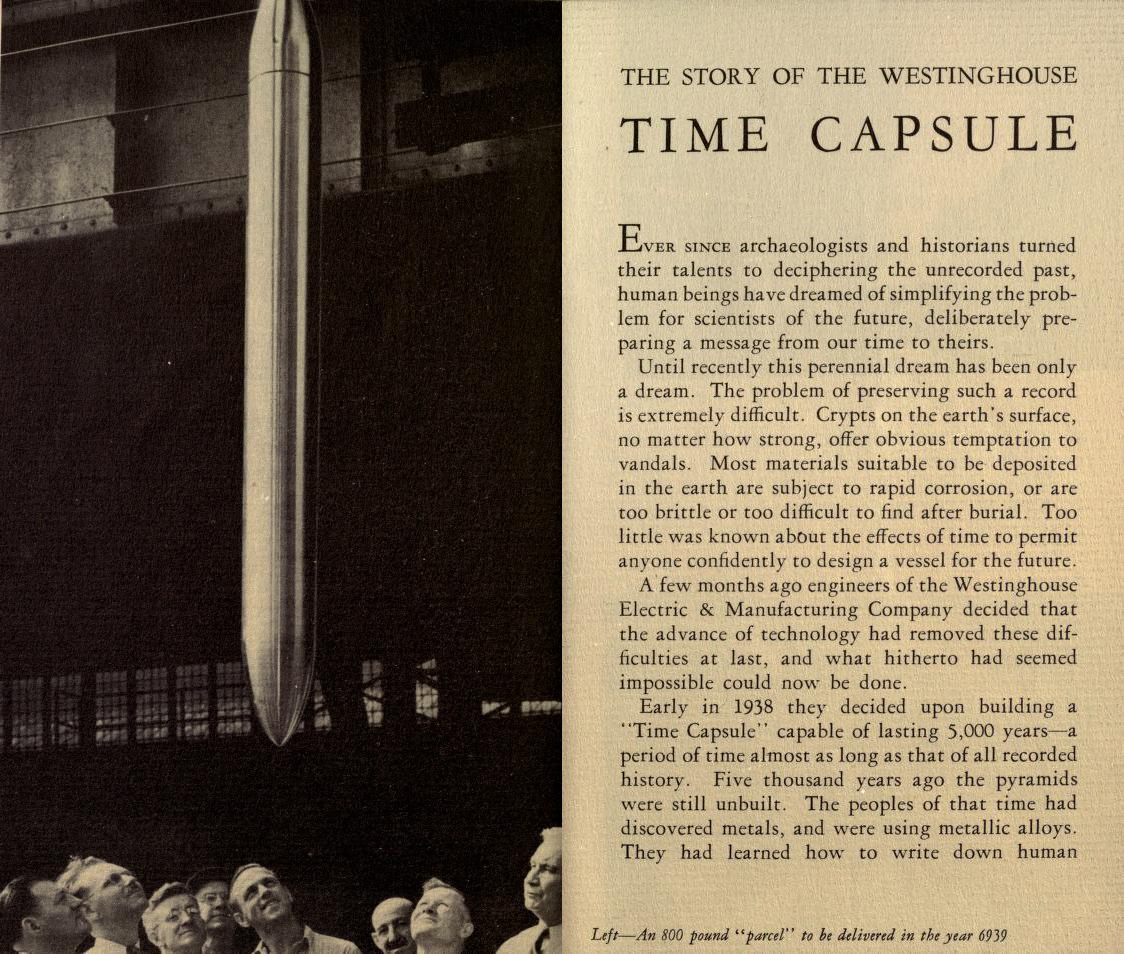

The term “time capsule” was coined in 1938, as a marketing trick. That year, the Westinghouse Electronics and Manufacturing Company, then the country’s second-biggest appliance retailer, hired a publicist named G. Edward Pendray to jumpstart their sales. Pendray was a big fan of rocketry, and he designed what was essentially an eight-foot thermos, shaped like a torpedo. Westinghouse invented a new super-durable alloy, called Cupaloy, for the capsule.

A postcard for the Westinghouse building at the 1939 World’s Fair. (Photo: Joe Haupt/CC BY-SA 2.0)

They filled the capsule with a Kewpie doll, a copy of LIFE, a bunch of seeds, and many samples of plastic. It would stay sealed, they said, for 5,000 years—enough time to put 1938 at “the halfway point of civilization.” They sold a commemorative book, explaining how “the learned among [future civilizations] may study with pleasure and profit things now in existence which are unique to our time.” (Reading the book gives you a sense of exactly what, according to Westinghouse, made the time unique: “We have… created dyes, materials, stuffs that Nature herself forgot to make,” it reads. “We have made metals our slaves.”)

“When they lowered the Time Capsule of Cupaloy into the ground, all the men instinctively whipped their hats off, because it was a solemn occasion,” says Jarvis. “The had a Chinese restaurant gong that they borrowed, and as they put the capsule down into the Immortal Well—which itself was some sort of plastic—they sounded it.” It was, perhaps, the first time mankind removed their hats for a piece of branded content.

Not everyone included in the capsule felt like bragging. Tucked into the cylinder among the material artifacts were missives from “Noted Men Of Our Time”: Robert Millikan, Thomas Mann, and Albert Einstein. Millikan describes the struggles of democracy against despotism, and Mann predicts that future readers of his message will be as dispirited as the people of his time. Due to war and uncertainty, adds Einstein, “any one who thinks about the future must live in fear and terror.” He ends on a wryly prescient note: “I trust that posterity will read these statements with a feeling of proud and justified superiority.”

Bureaucracy Goes to Space

When Carl Sagan was four years old, his parents took him to see the Time Capsule of Cupaloy. Thirty-eight years later, in the introduction to the Golden Records’ own commemorative book, Murmurs of Earth, he recalled the experience. “There was something very graceful and human in the gesture, hands across the centuries, an embrace of our descendants and our posterity,” he wrote. “For those who have done something they consider worthwhile, communication to the future is an almost irresistible temptation.”

Sagan bit this particular apple a few different times. In 1972, the famed astrophysicist and science communicator helped design the Pioneer plaques, which, like the Golden Records, were blasted into space on probes set to traverse the universe indefinitely. The diagrams depict a hydrogen atom, a pulsar map of the galaxy, and two nude human figures—a man with his hand up, and a slightly shorter woman in the background. Four years later, he took charge of a similar explanatory plate for the satellite LAGEOS-1, which will orbit Earth for 8.4 million years, tracking tectonic drift.

Dr Carl Sagan in Death Valley, California, with a model of the Viking lander, c. 1975. (Photo: NASA/Public Domain)

By the time astronomer F.D. Drake asked Sagan to help design a cultural hitchhiker for the Voyager probes, he was ready to go big. He wanted international music. He wanted multilingual greetings. He wanted a representative slice of the human race’s collective experience—images, songs and sounds that would explain not only what we were, but who we were, too.

This would have been a tall order regardless of time and funding, but the Golden Record team’s resources were nearly as limited as their goals were vast. Less than half a dozen people worked on it, and, after deciding on the project’s form and scope, they only had about six weeks to actually put the thing together. By their own account, the curation process was less like building a timeless cabinet of wonders and more like undertaking a kind of bureaucracy-boxed scavenger hunt.

In the best cases, these limitations lent a kind of rambunctious, Scooby-Doo feel to the proceedings. Sagan wandered the streets of New York in search of two rocks to clang together, hoping to sonically approximate the creation of the first stone tools. To get a special recorder delivered from Colorado as quickly as possible, the team booked it a plane ticket under the name “Mr. Equipment.”

An explanation of the Golden Record’s cover diagrams. (Photo: NASA/Public Domain)

In Murmurs of Earth, Anne Druyan, the record’s creative director, describes a breathless search for “Jaat Kahan Ho,” a raga performed by the Indian classical vocalist Kesarbai Kerkar and, at the time, long out of print. After ethnomusicologist Robert Brown insisted this was the only acceptable choice for First Raga In Space, Druyan called up every Indian restaurant in Manhattan for leads, and finally found three copies at an appliance store on Lexington Avenue. “Why I want to buy all three occasions a great deal of animated speculation on the part of the owners,” writes Druyan. “I fly out of the shop and race uptown to listen to it.”

At other times, though, the dream of representing the entirety of the planet ran hard into the particular strictures of the late-1970s United States. Take the otherwise inexplicable Senator list. Seeking recordings of greetings in various languages, Sagan approached the United Nations—but the UN couldn’t act without a motion from a national delegation, and the US Delegation wouldn’t move without the State Department, and the State Department wouldn’t budge without an okay from NASA. By involving this telephone-chain of organizations, Sagan accidentally solicited spacebound messages from the UN Secretary General and President Jimmy Carter, and a large list of the names of senators and representatives who didn’t want to be left out. NASA insisted he include either none of these gifts, or all of them. “So in case the reader wonders how it is, say, that Senator John Stennis of Mississippi has his name aboard the Voyager record,” Sagan writes, “I suppose it goes back to the nature of bureaucracies.”

Examining theWestinghouse’s Time Capsule II, at the 1964 New York World’s Fair. Both are buried in Flushing Meadows Park. (Photo: Austin Hall/CC BY-SA 2.0)

Murmurs of Earth is chock full of these stories—mandated additions, accidental exclusions, and strange in-between compromises. The records contain whale sounds, crickets, and Carl Sagan’s son, but no Swahili, because that particular volunteer missed his recording appointment. One of the earlier pictures on the record, of a child being born, includes the upside-down baby and a masked doctor, but no mother. (“In all photographs we looked at, the mother was so hidden by sheets that it wasn’t clear that it was a woman, or even a person, that was giving birth,” explains Jon Lomberg, who headed up the photo division.)

Other omissions were more purposeful. Early on, Lomberg writes, “we reached a consensus that we shouldn’t present war, disease, crime, and poverty”—for fear of riling up the aliens, or tainting what could, eventually, be the universe’s last remnant of humanity. NASA, gunshy after the Pioneer plaques led the public to accuse them of intergalactic smut proliferation, refused to let any more naked people into space, so the team sent two silhouettes instead, one with a line-drawn fetus inside. They imposed more rules, too—here is Anne Druyan on the recording of “Kiss:”

“This wonderful sound proved to be the most difficult to record. We were under strict orders from NASA to keep it heterosexual, and within such a constraint we tried every permutation we could think of without success. [Interscope Records head] Jimmy Iovine happened to show up that day, and he was most anxious to produce a believable kiss by sucking his arm. But this was to be that impossible thing, a kiss that would last forever, and we wanted it to be real. After many unusuable kisses that were too faint or too smacky, Tim [Ferris] kissed me softly on the cheek; it felt and sounded fine.”

One of the last photographs on the record is of an Antarctic Sno-Cat dangling helplessly over a yawning ice chasm, its attendant humans flummoxed by the situation. Lomberg describes this as a relatable joke—“freeing stuck vehicles may be an experience we share with alien explorers,” he writes—but in some ways, it’s a good metaphor for the whole project. After all, the Golden Records’ creators had their own particular regrets. Sagan famously wanted to include “Here Comes the Sun,” but although all four Beatles agreed, their publisher didn’t, and he couldn’t get the copyright clearance. Lomberg was a little skeeved out by the insect representative, a yellow wasp whose parasitic larvae eat their host alive. F.D. Drake, bemoaning the fact that the record’s sounds and images weren’t at all coordinated, imagines a future alien audience that is equally pressed for time, and thus empathetic. “Perhaps this will be nothing new to Them,” he writes. “Perhaps there will be a motion we wouldn’t recognize, to Them a nod, as They realize that a billion years before there had been a civilization little different from Theirs.”

Trash Capsules

An updated capsule for 2389, and which included special Kindles. (Photo: Courtesy Knute Berger/ Washington State Archives)

Knute Berger—professional time capsuler, World’s Fair historian, and founding member of the International Time Capsule Society—has spent a lot of time thinking about how best to bottle history. He can tell you the pros and cons of most archival materials (terra cotta is your best bet). He’s searched the Capitol, unsuccessfully, for George Washington’s lost cornerstone capsule—which, he says, “could be in a rock pile somewhere.” Bit by bit, he has amassed his own internal time capsule collection, stacked to the roof with stories, examples, and best practices.

Over years of research, one theme really stands out: “I’ve learned a lot about how many of them get lost,” says Berger. The vast majority of time capsules, he explains, are made by amateurs, many of whom are less concerned with the actual future than with commemorating the present, or giving themselves a long-term gift. “They’ll never do another time capsule,” he says. “It’s a one-time thing.”

Time capsule mistakes are manifold. Rookies choose the wrong packaging, and leave their descendants to dig up boxes of green slime, or bags of soggy garbage. They neglect to airlock their concrete bunker, and end up, like this Tulsa town, with a completely rusted-out Plymouth Belvedere. Mostly, like nut-crazed squirrels in the fall, they fail to mark, write down, or otherwise remember their burial sites. “People think memory is stronger than it is,” says Berger. “I spend a lot of time looking for my glasses and my car keys—but somehow we think if we have a ceremony and we put something in the ground, then everybody’s going to remember.”

The frontispiece to the booklet The Story of the Westinghouse Time Capsule, praising “what hitherto had seemed impossible could now be done”. (Photo: Internet Archive/Public Domain)

Even large organizations, with their collective brainpower, can’t seem to get it right. In 1953, Washington State buried a sofa-sized metal tube full of midcentury goods—“but the legislature wouldn’t float the money for a marker, and so they forgot where it was,” Berger says. The U.S. Bicentennial capsule, made up of 22 million American signatures, was stolen by outlaws during its 1976 cross-country wagon train tour, and has never been found. MIT buried a time capsule under the lid of a cyclotron in 1939; fifty years later, they realized they couldn’t move the machine’s 18-ton lid, so they left it there. (Meanwhile, last year, Cambridge construction workers accidentally unearthed another MIT capsule that was meant to lay dormant until 2957.) Listening to Berger rattle off lost capsules, you get the feeling that the ground you’re standing on is filled with layer upon layer of hopeful artifacts, accidentally left to rot.

The Golden Records, Berger says, were anything but an amateur attempt. As someone who is always trying to avoid relying on outdated tech, he admires their analog nature, which ensures that—materially, at least—they won’t fade into obsolescence. The strategies they use for dealing with potential communication issues—the diagrammatic record-playing instructions, and what he calls the “Rosetta Stone quality” of the 50 recorded greetings—remind him of other grand, sweeping capsules, like the Crypt of Civilization, which contains a hand-cranked machine meant to provide future discoverers with rudimentary English lessons.

Indeed, the Crypt of Civilization may be the Golden Records’ closet terrestrial equivalent. Housed in an old swimming pool at Atlanta’s Oglethorpe University, it has a similarly broad scope. It was first proposed by professor and clergyman Thornwell Jacobs in 1936 to preserve the “life, manners and customs of the present civilization” for posterity, and is set to be opened in 8113 A.D. In the meantime, you can browse its inventory—which, if you’re looking for them, boasts its own set of weird contents: six Artie Shaw recordings; an electric Toastolator; a “sample of gold mesh;” two white dolls and one Black one; a proportionally strange amount of women’s underthings. Civilization, indeed.

To Berger, true time capsule judgment should be reserved for the intended audience—“I mean, how do you put together a record that doesn’t seem like something you’d find at a garage sale?” he asks. But he still thinks we can do better. In 1989, his home state’s Centennial Commission tapped Berger to organize a large project, the Washington State Time Capsule, which he hopes will overcome some of these failings.

The sealing ceremony of Centennial time Capsule Project in 1990. Knute Berger is on the right, and the girl is one of the ‘Keepers of the Capsule’ who updated the capsule in 2014. (Photo: Courtesy Knute Berger/ Washington State Archives)

Because individual time capsules so quickly outdate, he’s set up a warren of 16 of them, set to be filled one at a time every 25 years. Because they tend to be so strange when stripped of their context, he’s focusing more on individual experiences than any attempts at sweeping best-ofs. And, thanks to all the loss problems he’s seen, he’s training the next generation as “capsule-keepers,” sworn to responsibility by the state in adolescence, when memories really stick. He and his team filled the second capsule in 2014. It covers the years since 1989—“essentially a lot of Amazon and grunge,” he says.

“My argument was, we’re creating the layers of an archaeological site,” he says. “What you’ll see over time is how our thinking evolved, and how the concept of the time capsule evolved.” Layer upon layer of weirdness—what else is history, after all? “Some of it’s intentional, some of it’s random, and some of it’s completely unpredictable,” he says. “But you hope something in there sticks.”

Artifacts and Artefictions

Alien scholars may not get their tendrils on Voyager for another 10,000 years or so, but thanks to the intense documentation of its creation, human ones are already all over it. Dr. Alice Gorman, a space archaeologist at Australia’s Flinders University, studies the Golden Records as artifacts, subject to anthropological scrutiny. “There’s a long tradition of putting things on spacecraft that have some kind of personal or cultural meaning,” she says. “I’m interested in the choices people make about what to send along.”

The Pioneer plaque, designed by Carl Sagan. (Photo: NASA/Public Domain

Gorman began by looking deeper into the two Aboriginal songs on the records. In Murmurs of Earth, they are listed as “Morning Star” and “Devil Bird”—but as Gorman eventually found out, the songs are mislabeled. “Devil Bird” is actually “Moikoi”—a song, Gorman writes, about “malicious spirits who try to entice newly deceased souls away from their clan country.” Though this won’t matter to the aliens, who aren’t privy to the liner notes, it does confuse human scholars trying to better understand the record’s contents.

Murmurs of Earth also lists the people who recorded the songs rather than those who performed them—“so next up was saying, who are the musicians, who are the people?” Gorman says. She traced the songs’ provenance back to three men: Djawa, a community leader and artist; Mudpo, a didjeridu player, and Waliparu, an older man. “There’s a whole other layer of identifying and situating them in the story,” she says. This applies to most of the non-Western music—who is playing that melancholy Japanese shakuhachi? Which young Peruvian girl is hurtling through space singing an Incan “Wedding Song”?

The same goes for nearly all of the photographs, which identify Jane Goodall, French climber Gaston Rebuffat, and American gymnast Cathy Rigby, but none of the Filipino parents, Balian dancers, or laughing Chinese family members. A picture from the Olympics comes with a caption naming Russian champion Valery Borzov, and calling the second, third and fourth place finishers “two black men and an Oriental.” Another shows an anonymous black woman peering into a microscope. Gorman has been trying to track her down. “We’ve had all these debates in recent times about the role of women in science and how women of color are marginalized,” she says. “And here in 1977 there’s a black female scientist, and we don’t even know who she is!”

John Casani, Voyager project manager, with the golden record (left) and its cover (right), August 4, 1977. The Voyager 2 is behind him; the American flag was sewn into the thermal blankets of the spacecraft. (Photo: NASA/Public Domain)

The Golden Record’s curators got many of their images and songs from other sources—photo archives, music libraries, and sound collections, many of which failed to provide exhaustive information. But this persistent lack of certain details is telling, regardless of exactly where it comes from. “[Sagan was] so thoughtful, and they were making efforts to be inclusive across the board,” Gorman says, “but they were people of their time as well. The meanings of these pictures, and the relationships between the different themes, are telling stories they never could have imagined.”

These days, Gorman points out, you’d never make the Golden Record the way Sagan and his compatriots did. Most more recent attempts at interstellar communication are unabashedly crowdsourced. The New Horizons Message Initiative, also helmed by Golden Record team member Jon Lomberg, recently announced a plan to send a “global self-portrait” to New Horizons, made up of submissions from people across the world. “It was very presumptuous of Carl Sagan and the rest of us to speak for Earth [in 1977],” Lomberg told National Geographic in 2014, “but at the time it was either do it that way or don’t do it at all.”

Of course, it’s presumptuous to add to a crowdsourced self-portrait, too. It’s presumptuous to assume aliens or future kings are listening, or to bury something and expect you, or anyone else, will remember to dig it up. When you’re dealing with the future, presumption is the whole point. And the things we presume may tell our future selves more about us than the baubles, snippets, and images we carefully choose to present.

Update, 5/26: The article has been updated to reflect the fact that Dr. Alice Gorman teaches at Flinders University, not the University of Adelaide. We regret the error.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook