The Secret Jokes Hidden in Alice in Wonderland

W. Butcher & Sons, Alice in Wonderland, London, 1905-1908, Magic lantern slides. (Photo: Gift of Arthur A. Houghton, Jr./Photography by Graham S. Haber, 2015./Courtesy of the Morgan Library)

W. Butcher & Sons, Alice in Wonderland, London, 1905-1908, Magic lantern slides. (Photo: Gift of Arthur A. Houghton, Jr./Photography by Graham S. Haber, 2015./Courtesy of the Morgan Library)

Just about everyone knows Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (or Alice in Wonderland, the nickname most of us use). But before it was a Disney movie, several dozen other movie and TV adaptations, a Disneyland ride, a video game, a manga, 170 translations, or even a published novel that in 150 years has never gone out of print, it was a story told to entertain some little girls on an afternoon boat trip on the Thames.

In fact, the original story, Alice’s Adventures Under Ground, might be best understood as having a target audience of three: Alice’s namesake, Alice Liddell, and her sisters. It was committed to writing at Alice’s request, and it’s filled it with the Victorian equivalent of Easter eggs meant to make her and her sisters smile.

Thanks to 150 years of scholarship, though, we can share in the private jokes.

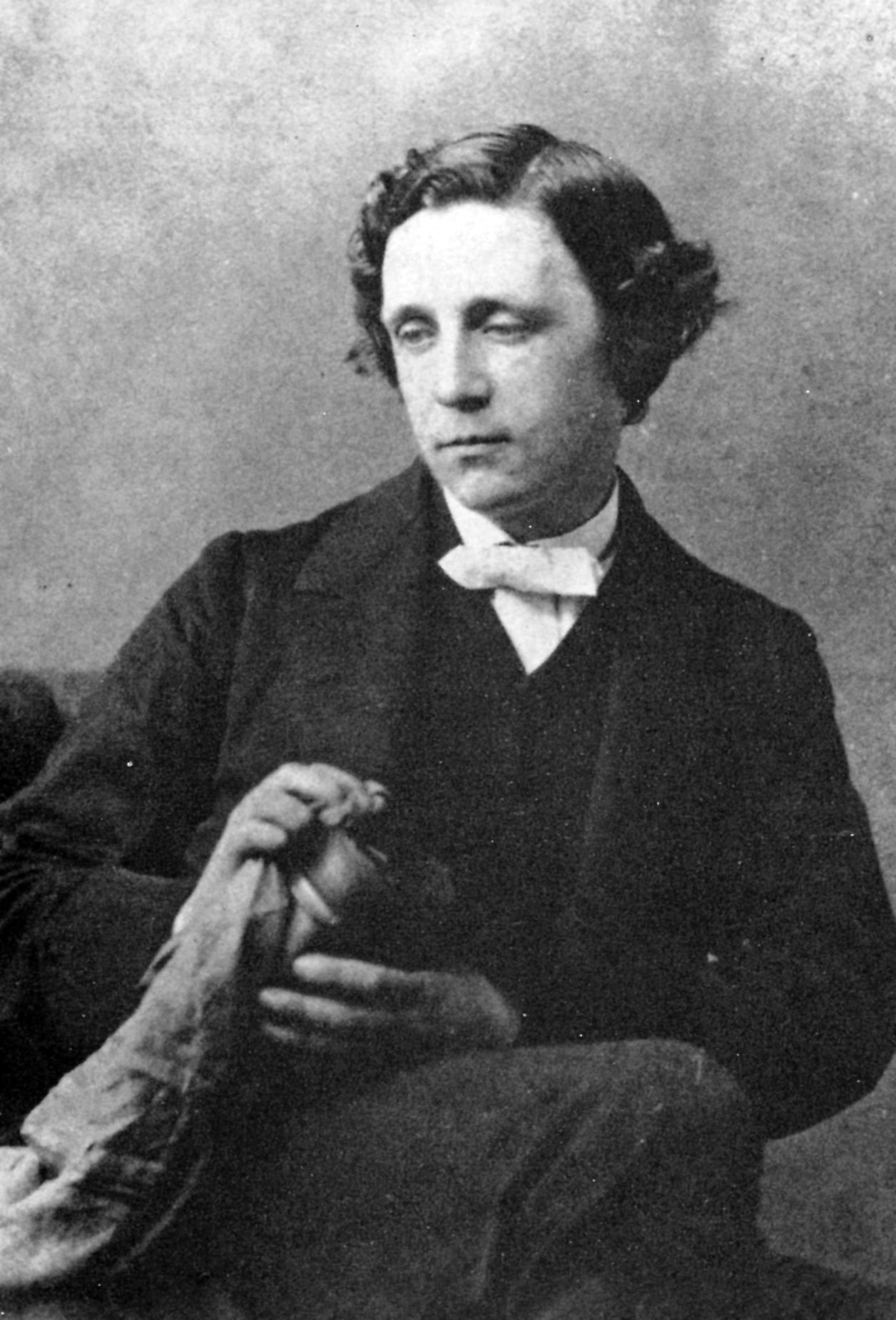

Portrait of Lewis Carroll by Oscar G. Rejlander. (Photo: Public domain/WikiCommons)

On a July day in 1862, Alice Liddell, ten years old, and her sisters Lorina and Edith were rowing with their grown-up friend Charles Dodgson, a mathematician who had recently started publishing his writing under the pen name Lewis Carroll. Carroll and one of his friends were bringing the Liddells to the town of Godstow for a picnic, and while he rowed he told them a story. Carroll was particularly fond of Alice—he had a lot of little girl friends, a fact that many later readers have found unsettling—and he named the heroine of the story after her.

Dodgson called his original manuscript Alice’s Adventures Under Ground, since it starts with the heroine falling down a rabbit hole. (Getting children into fantasy worlds through geological formations was not an uncommon approach in Victorian-era fairy tales, according Carolyn Vega, assistant curator of literary manuscripts at the Morgan Library, which just closed an exhibition about Alice. Charles Kingsley’s novel The Water-Babies, for instance, has its protagonist enter fairyland by falling into a river.) It’s easy to forget that the adventure was meant to take place inside the earth, since Wonderland is full of trees and animals, but Lewis always described it as an underground adventure. A. L. Taylor, in his book The White Knight, suggests that the Mad Hatter’s watch only tells the day of the month (and is “two days wrong”) because Wonderland is close to the center of the planet, where it makes more sense to run on lunar time than solar. The moon’s cycle would be consistent even underground where the position of the sun is meaningless, Taylor argued, and the difference between the lunar and calendar months is two days. As Martin Gardner writes in The Annotated Alice, “it is hard to believe that Carroll had all this in mind.”

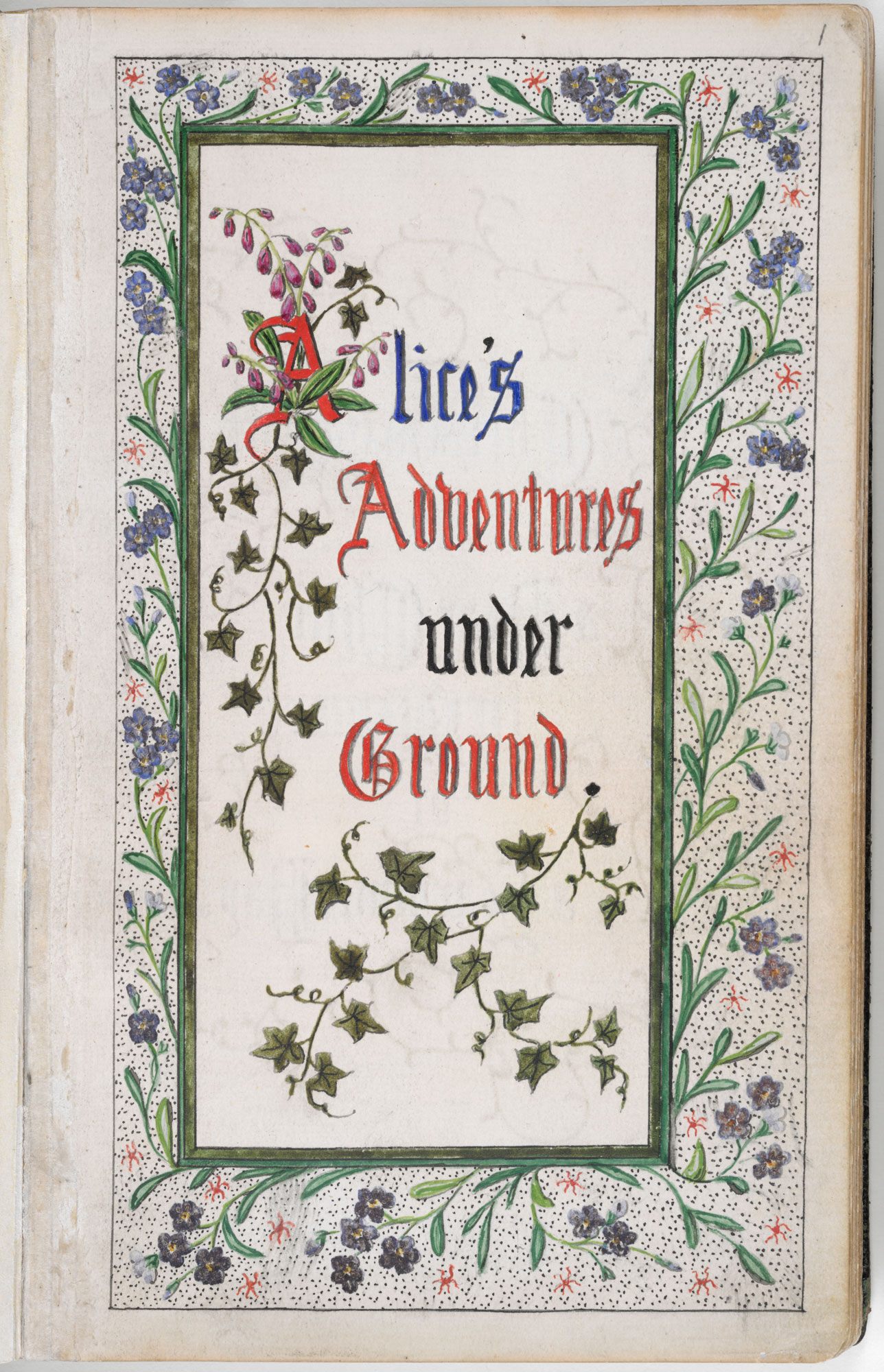

The title page of Lewis Carroll’s manuscript for Alice’s Adventures Under Ground. (Photo: Public domain/British Library)

For publication, Carroll came up with a few different titles, such as Alice’s Golden Hour, Alice’s Hour in Elfland, and Alice Among the Goblins, before settling on Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Though Carroll coined many words we still use today—chortle, snark, galumph—“wonderland” wasn’t one of his; it first appeared 75 years earlier, in Peter Pindar’s A Complimentary Epistle to James Bruce, Esq.: the Abyssinian Traveler. But Vega says it wasn’t in popular use, and we can probably credit Carroll for the way that “wonderland” has become a universal term for a place full of marvels.

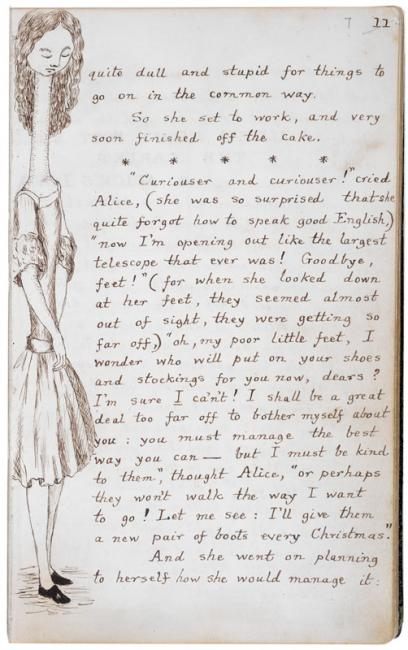

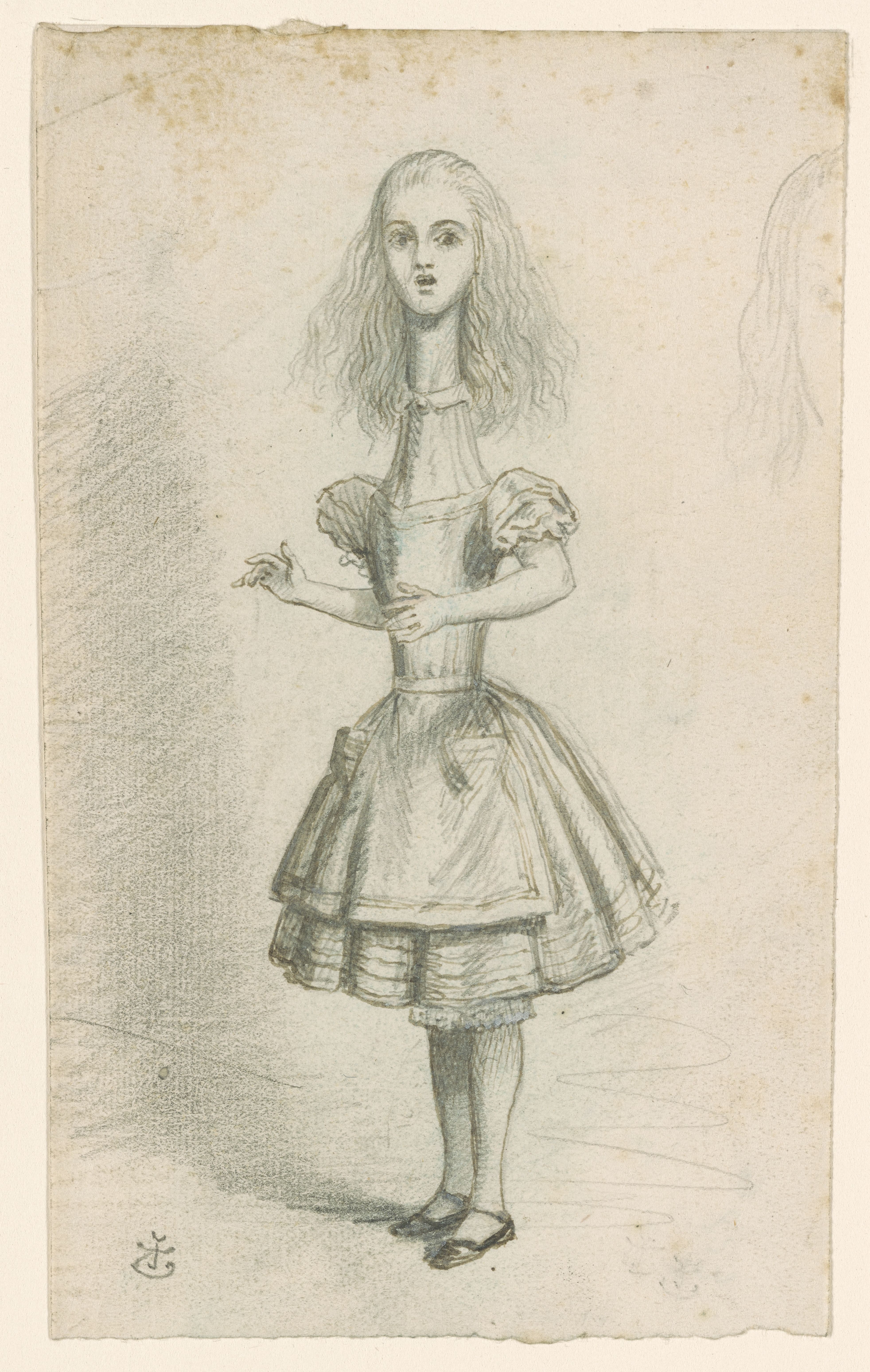

In many ways, Alice’s Adventures Under Ground was a very different book from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland– but not because of its text. Wonderland’s words went through some changes on the way to publication (for instance, Carroll added the Mad Hatter’s tea party and the “caucus-race,” where Alice and several animals run in dizzying circles), but for the most part the story was preserved. The MS, though, didn’t have Tenniel’s iconic illustrations. Instead, it was decorated with Carroll’s sketches of a darker-haired Alice. Neither Carroll’s nor Tenniel’s drawings were based on the real Alice Liddell—Tenniel, in fact, said that his were based on nobody in particular, since he never worked from a model—but Carroll did attempt a portrait of the real Alice on the very last page of the manuscript. He wasn’t happy with it, and pasted a photograph of Alice over the sketch; his original drawing was not discovered until the 1970s.

Carroll’s original illustration of Alice grown tall after eating a cake marked “Eat Me.” Compare to Tenniel’s interpretation, below. (Photo: Public domain/British Library)

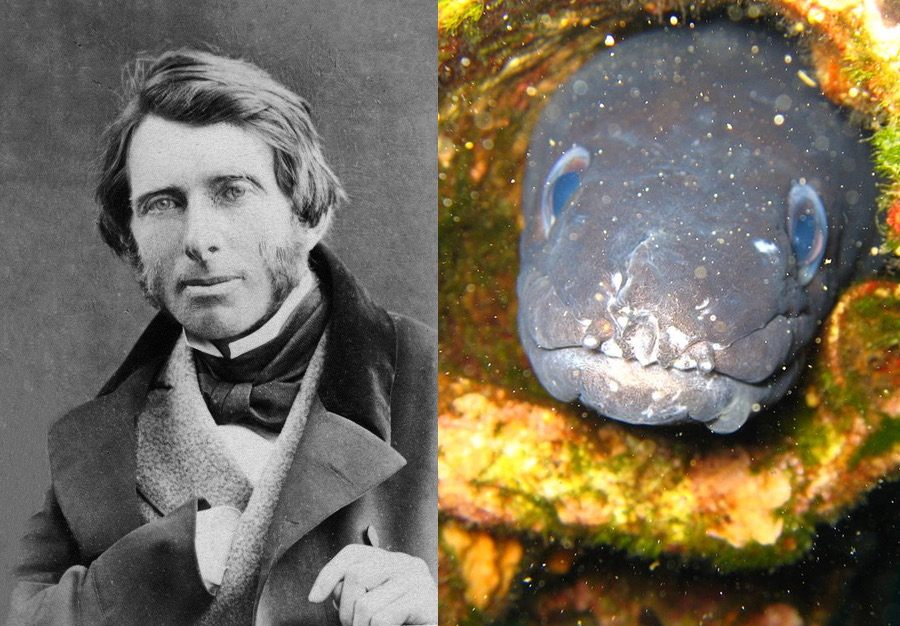

More than anything, though, Alice’s Adventures Under Ground differed from the final work in its intended audience. Originally invented as a diversion for the Liddell sisters, the story contains a number of references that may seem purely weird to modern readers, but would have been delightful, sly jokes to the girls themselves. Anyone might giggle, for instance, at the Mock Turtle’s description of his “Drawling-master” when he was a schoolboy, an “old conger-eel” who taught “Drawling, Stretching, and Fainting in Coils.” But the Liddell children in particular would recognize their drawing-master, art critic John Ruskin–tall, thin, and not un-eelish–who taught them drawing, sketching, and painting in oils.

Left: John Ruskin. Right: A conger. (Photos: Public domain/WikiCommons; Public domain/WikiCommons)

The girls would also have recognized the Dodo, whom Alice encounters shortly after falling down the rabbit-hole, after she becomes tiny and is caught up in a flood of her own tears. That’s because the Dodo was Lewis Carroll himself. The choice of bird is a reference to his stutter; he would sometimes pronounce his own last name as “Dodo-Dodgson.” The Dodo’s companions the Duck, the Lory, and the Eaglet also represent passengers on the boat trip where Carroll first told the story of Alice’s adventures. They are Carroll’s friend Robinson Duckworth, and Alice’s sisters Lorina (Lory) and Edith (Eaglet). (Lorina, Edith, and Alice also reappear in the Dormouse’s tale as the three sisters who live in a treacle-well.) The long-winded Mouse may represent Mary Prickett, the Liddells’ governess.

As for who inspired the Mad Hatter, there’s some dispute. For a while, the character – or, at least, Tenniel’s illustration of him – was presumed to be based on Theophilus Carter, an Oxford cabinet-maker who had also invented an “alarm clock bed” which would dump a sleeper unceremoniously on the floor. This assumption was largely based on letters to the Times of London in the 1930s, 60 years after Wonderland was published, and the image of the Mad Hatter as an inventor of equally mad alarm clocks was apparently too good to check. Sadly, there’s no evidence of a connection between Carter and Carroll, or Carter and Alice Liddell – and no evidence, either, that he ever really made that alarm clock bed. Perhaps more likely, the figure of the Hatter could be based on shopkeeper Thomas Randall, later mayor of Oxford, whose home the Liddells visited regularly and whose dog, Rover, Alice would sometimes be allowed to walk.

John Tenniel (1832—1914), “Curiouser and curiouser!” Final drawing (graphite on paper), 1864-1865. (Photo: Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Benjamin Gale/Photography by Steven H. Crossot, 2014/Courtesy of the Morgan Library)

Many of the poems in Alice in Wonderland, which modern readers might see as pure whimsy, were in fact nonsensical parodies of verses that Victorian schoolchildren had to learn by heart. When Alice, in the book, recites “How Doth The Little Crocodile,” she’s trying to remember Isaac Watts’ “Against Idleness and Mischief,” an altogether more moralistic work that begins “How doth the little busy bee / Improve each shining hour.” Watts also wrote “The Sluggard,” a poem warning about the dangers of sloth, which is parodied in Wonderland as “‘Tis The Voice Of The Lobster.” “You Are Old, Father William” is also based on a didactic poem, “The Old Man’s Comforts And How He Gained Them” by Robert Southey.

Unlike Father William, Southey’s old man doesn’t stand on his head or balance eels on his nose; instead, he admonishes his young questioner to take care of his health, think of the future, and remember God. The Liddell sisters “would have gotten a lot more out of some of these jokes,” Vega told me, because they were so familiar with the dry, preachy originals.

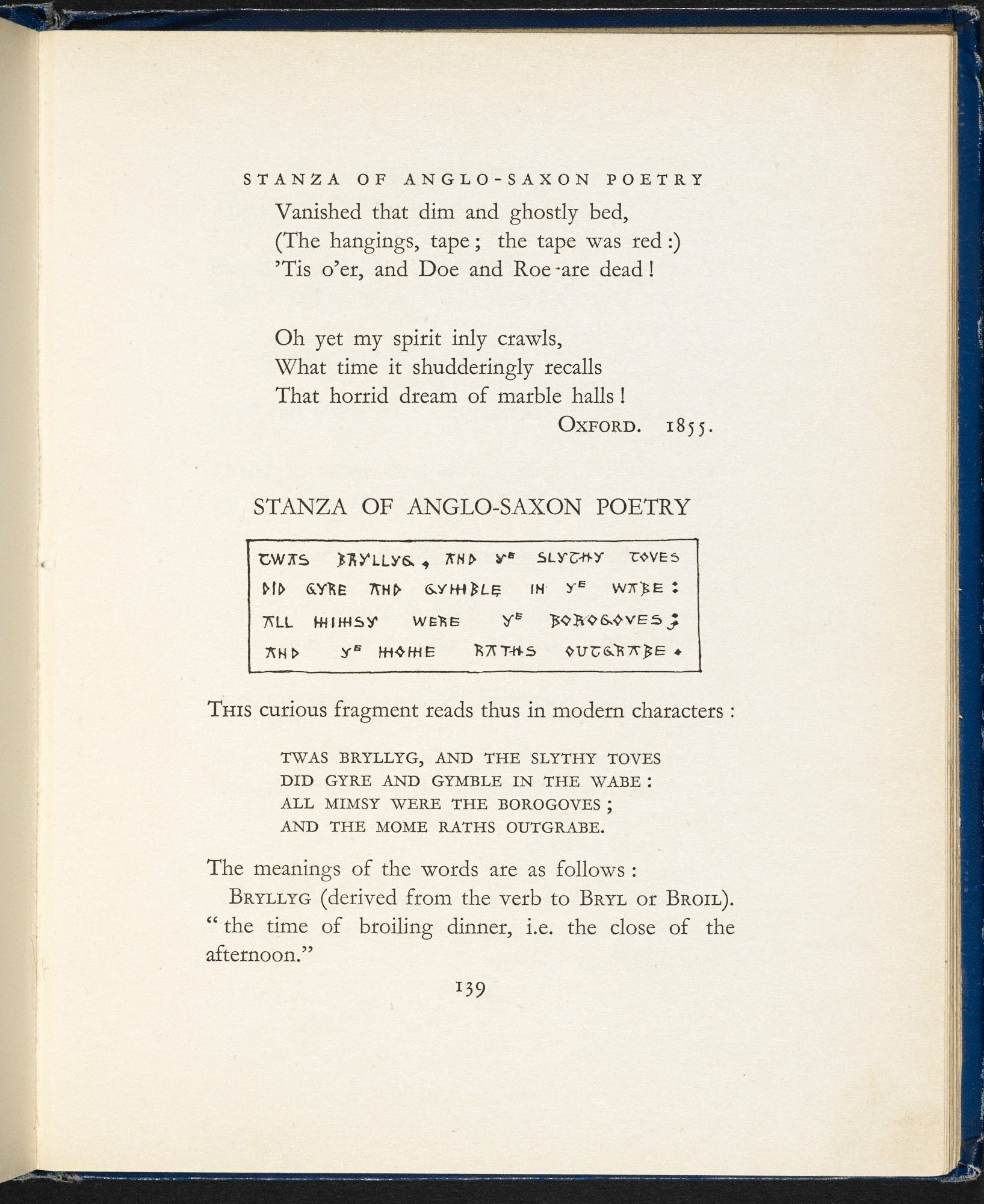

Incidentally, Carroll continued this tradition of parody in Through The Looking-Glass, along with purely original inventions like “The Walrus and the Carpenter” – though the subjects of his mockery were a bit more highbrow. “Haddocks’ Eyes” has shades of “Resolution and Independence,” by William Wordsworth, and is sung to the tune of a poem by Thomas Moore. Another poem parodies Sir Walter Scott’s “Bonnie Dundee.” And while the Liddell sisters wouldn’t have recognized the origins of “Jabberwocky,” Carroll’s family would. He composed the first stanza when he was only in his teens, and published it in a magazine he wrote and illustrated for his siblings. The poem, carefully rendered in faux-Runic script, was accompanied by a language key similar to the definitions Humpty Dumpty offers in the book.

Original first stanza of “Jabberwocky,” written when Carroll was a teenager. (Photo: Public domain/British Library)

Wonderland also had one final secret gift for Alice: if you note textual clues about the month and day, you’ll find that the adventure takes place on May 4. That’s the real Alice Liddell’s birthday.

Of course, you don’t need to be Alice Liddell, or even a Victorian schoolchild, to appreciate Alice’s adventures. It’s no accident that Carroll’s nonsense verses are widely recognized while the didactic poems they’re based on are nearly forgotten, and characters like the Mad Hatter are indelible even if you’ve never met Thomas Randall or Theophilus Carter. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is a bona fide deathless classic. But before it was a classic, it was a whimsical tale full of inside jokes for a specific, beloved little girl.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook