The Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum Hosts a Rare Open House This Saturday

Flak Bait sits piece-by-piece in the gigantic Mary Baker Engen Restoration Hangar in Chantilly, Virginia (all photographs by the author)

Flak Bait sits piece-by-piece in the gigantic Mary Baker Engen Restoration Hangar in Chantilly, Virginia (all photographs by the author)

It is generally agreed upon that air and space meet at approximately 62 miles above sea level. This is where a barrier exists, the Karman Line, that when passed, the atmosphere thins out and outer space begins. Here on Earth, that divide is celebrated at the corner of Independence Avenue and 6th Street Northwest in downtown Washington, DC, and off Sully Road in Chantilly, Virginia.

These two complexes of the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum are two of the most visited museums in the world, where visitors of all ages can ogle the breath-taking machines, instruments, and tools that have taken us all the way to the moon and back. But beyond the curated displays, there is work going on to allow these pieces of history to survive for generations to come. The Smithsonian Institution is not just a place to store history, but to bring back history.

This Saturday, January 24, at the Uday-Hazy Center, the public will be allowed behind-the-scenes access to view these artifacts and talk to the conservationists who are working on them.

This week at a press preview, the Udvar-Hazy Center presented a public look on the behind-the-scenes work that goes into restoring, conserving, and reviving America’s aeronautical and space exploration past. The historians, scientists, archivists, and conservationists have to deal with all sorts of issues, from fading paint to rotting organic material to mice who made their home in a B-26 Marauder’s rudder. As Malcolm Collum, Air and Space’s chief conservationist, puts it: “As conservationists, we take the hippocratic oath like doctors. Anything that is brought to us, no matter the historical or cultural value, we try to save, restore, and conserve.”

The items we got to see up close include several of the country’s most prized aerospace icons.

Flak Bait close-up

Flak Bait close-up

Flak Bait survived more operational missions than any other American aircraft during World War II, completing 207 over Europe. While the forward fuselage was on view in the museum on the Mall since 1976, the new project is to restore and display the entire aircraft. One of the more unique aspects of this is figuring out a way to save the old fabric of the aircraft by possibly adhering it to new, sturdier fabric — a method conservationists at Air & Space have never tried before on an aircraft.

The Apollo Telescope Mount that was supposed to fly on Skylab, America’s first space station.

The Apollo Telescope Mount that was supposed to fly on Skylab, America’s first space station.

Before the International Space Station, there was Skylab — NASA’s first space station, launched in 1973. With the first Skylab’s complications, among them regulating heat, the second Skylab never got off the ground. Attached was intended to be the Apollo Telescope Mount, a solar observatory and the first space-born telescope that would look at the sun across the electro-magnetic spectrum. Today, conservators are preparing this unique artifact to be shown to the public.

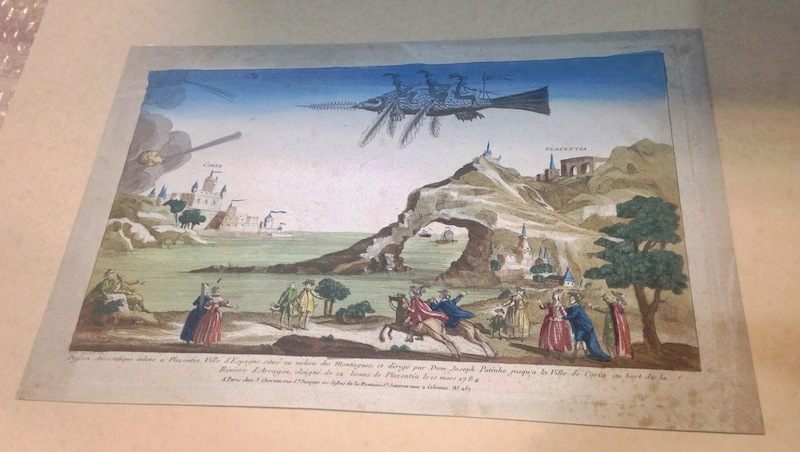

A late 19th century print depicting an odd fish-like aircraft.

A late 19th century print depicting an odd fish-like aircraft.

Among of the oldest artifacts in the Air and Space collection, and recently obtained, are prints, mother-of-a-pearl fans, and a band box that date back to between the 18th century and 19th century that depict various magical and fantastical flying machines, including one that a curator called “the flying fish.” Depicting three people sitting backwards (and possibly rowing?) on an airborne fish, the print is vibrant, whimsical, and rather bizarre.

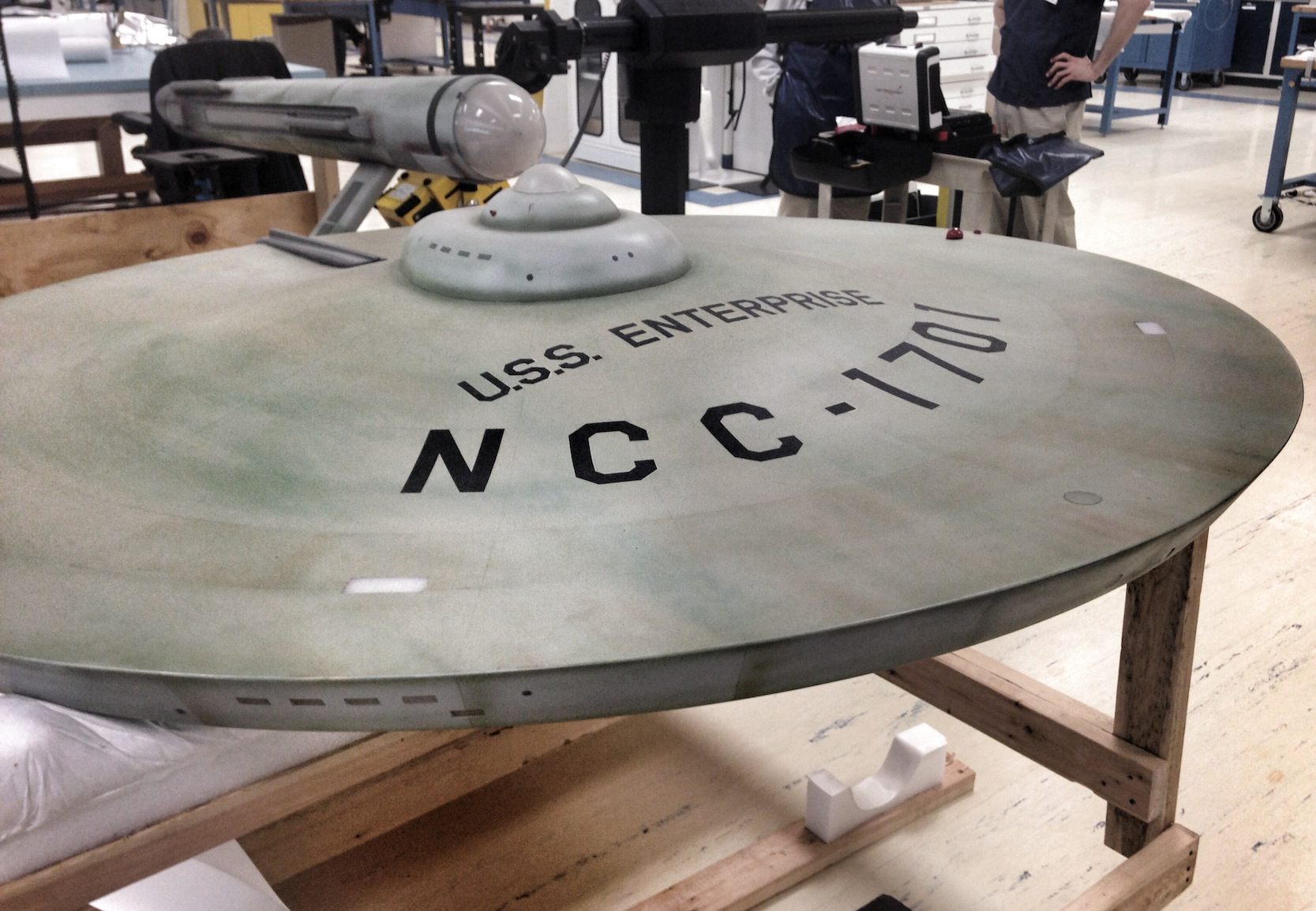

The USS Enterprise

The USS Enterprise

One of the most recognizable and beloved spacecraft of all time never went to space. Spending most its life on a Hollywood sound stage, the Starship Enterprise was hanging in the Air and Space gift shop for nearly 40 years, until it was brought down for restoration. What researchers discovered was that the Enterprise was falling apart, for it was a Hollywood prop and never meant to survive beyond the several years the show needed it for shooting in the 1960s.

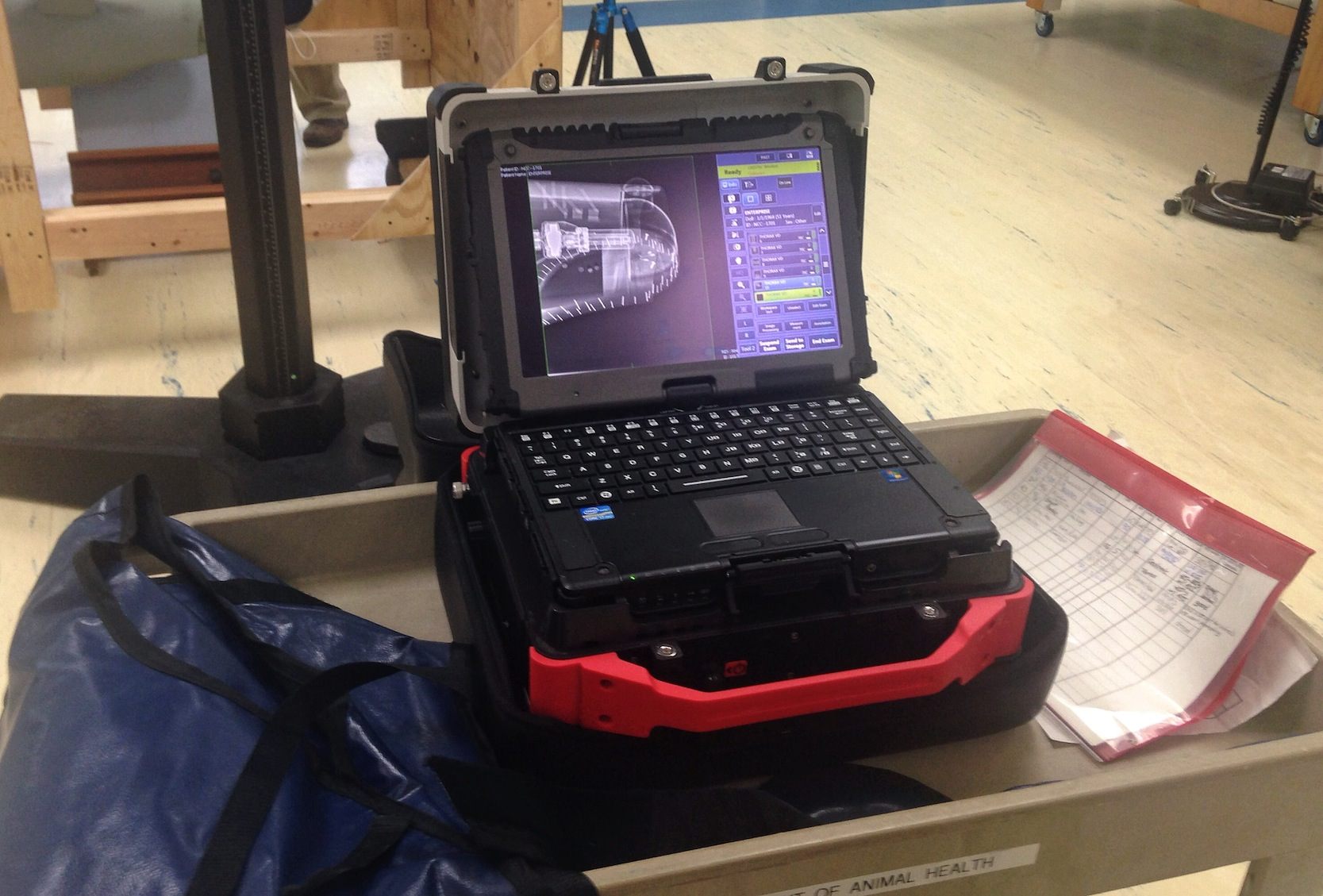

In order to figure out what needed repair inside the model, conservators brought in an X-ray machine normally reserved for the furry residents of the National Zoo. They discovered cracks, screws, and even a light inside the model that will need attention.

X-ray from the National Zoo

X-ray from the National Zoo

Work on all of these items is extremely detail orientated with long project times (in the case of Flak Bait, it will take more than five and half years for restoration). So, don’t expect these one-of-a-kind artifacts in the museum immediately.

The Smithsonian Air and Space Museum’s Udvar-Hazy Center Open House is free to the public this Saturday from 10 am to 3 pm.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook