The Sober Truth About Field Sobriety Tests

Does this woman look drunk? There are only a few tests that are proven to tell. (Photo: Oregon Department of Transportation/Flickr)

If you haven’t experienced it in person, you’ve definitely seen it on TV: a police officer pulls over a suspected drunk driver and makes them touch their nose and walk in a straight line to see how drunk they are.

Such field sobriety tests, or FSTs, have been around since police have been pulling over erratic drivers, but it wasn’t until 1975 that the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) decided to find out which, if any, were actually effective.

To this day, only three tests are officially sanctioned—and all come from the same decades-long study that started in the 1970s.

Prior to 1975, FSTs were developed independently within individual police forces without any empirical study or validation, other than the anecdotal experience of the officers who used them. In an effort to bring some order to the law, the NHTSA enlisted the Southern California Research Institute (SCRI) to begin testing some of the most commonly used FSTs. The hope was that by standardizing the tests, they would be easier to admit into court. Their prevalence in TV and film became a byproduct of that.

Six initial tests, culled from police agencies across America, were studied, but in the end, only three tests were found to be even somewhat consistently effective at ferreting out drunks. The SCRI conducted three studies between 1975 and 1983 that took place both in a lab setting and out in the field. After their studies concluded, the top three tests that won out over the others were the Follow-the-Finger test (actually called the Horizontal Gaze Nystagmus test), the Walk-and-Turn test, and the One-leg Stand test. Each was designed to look for different signals of impairment.

The Horizontal Gaze Nystagmus (HGN) test is more familiar than it sounds. This is the one where an officer asks a suspect to follow their finger or a flashlight with their eyes. Nystagmus is a kind of involuntary eye twitch, and it gets much worse when you’re drunk. By making you track an object, police are looking for how smooth your reaction is and whether your eyes are jerkier than they should be. The test is done in a side-to-side motion because it is more effective than an up-and-down motion.

Kind of like dance steps, which are also hard to follow while drunk. (Photo: State of New Jersey)

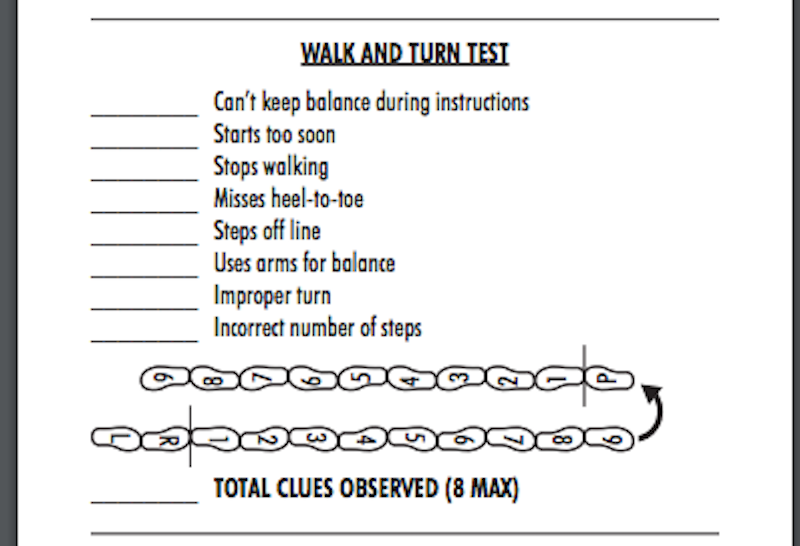

The Walk-and-Turn test is just like it sounds. Officers ask a suspect to walk the line, taking nine steps, heel-to-toe (it is unclear why nine is the magic number). They look for lack of balance or inability to follow instructions. If you use your arms to balance, that can also be a sign that you’re over the limit.

Finally, the One-Leg Stand test is another balance test that is challenging after even one beer. Here, a suspect lifts one foot out in front of them, and holds it there until the officer says to stop. Among the official no-nos that will give you away in this test are using your arms to balance, swaying, or hopping.

Surprisingly, even these winning tests didn’t turn out to be all that effective in determining drunkenness. During the initial studies, the HGN test (the most successful) was only proven to be 77 percent effective, while the Walk-and-Turn was only shown to detect drunkenness 68 percent of the time, and the One-leg Stand test 65 percent. Despite these rather unimpressive numbers, these three tests became the new standard among police agencies, and were used as evidence of drunk-driving in court.

During the 1990s a series of further validation studies was conducted in Colorado, Florida, and California that solidified the big three tests—now known collectively as the Standardized Field Sobriety Tests (SFSTs)—as the national standard. In these studies, police officers administered the tests, as opposed to the egghead researchers from the previous study. WHen used in combination, the three tests correctly picked out drunk suspects well over 90 percent of the time. To this day, the SFSTs are the only scientifically studied and proven field sobriety tests.

Of course, this does not mean that officers are required to use them exclusively. Many other non-standard tests are still used, in real life and in movies and TV. There is the Alphabet Test, in which a driver is asked to recite the alphabet backwards, or just a portion of it between two letters. Another popular test, if pop culture is to be believed, is the Finger-To-Nose test where an officer asks someone to extend their arms and touch their finger to their nose. While the former seems too difficult to be accurate, the latter seems too simple. Since they have never actually been tested, it’s impossible to prove how effective they are. But they sure do look good on camera.

FSTs are a contentious bit of policing even to this day, with entire websites detailing their failings and ways to discredit them. As breathalyzer technology continues to improve, they may soon be a thing of the past. But it seems unlikely that they will disappear from our popular consciousness any time soon.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook