5 Objects That Illuminate the Medieval Exchange Between Africa and Europe

A new exhibit explores the impact trade had on both cultures through artwork and artifacts.

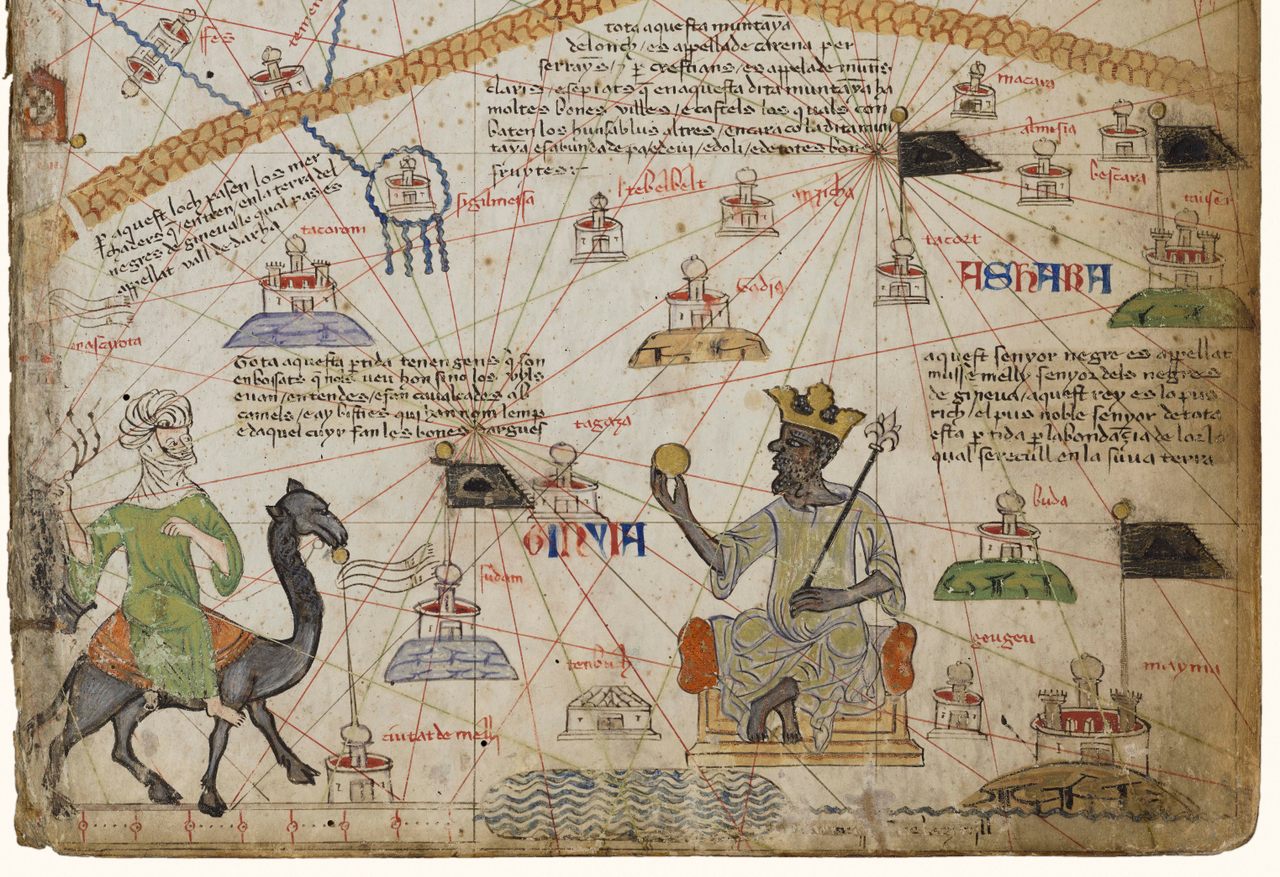

During the medieval period, between the 8th to 16th centuries, West Africa was flush with vast resources and gold. Its kingdoms were some of the most prosperous the world has ever known. When the king Mansa Musa of 14th-century Mali made a stop in Cairo, Egypt, it’s said that he handed out so much gold to the poor that he single-handedly caused mass inflation.

The riches of Africa were no secret to Europe. Much of the gold and ivory medieval Europeans used to cast religious relics, statues, and jewelry came directly from West Africa.

A new exhibit coming to The Block Museum of Art at Northwestern University explores this important historical relationship. Caravans of Gold, Fragments in Time: Art, Culture, and Exchange Across Medieval Saharan Africa features artifacts from West and North Africa, Europe, and the Middle East. These items highlight the economic hubs that were the African kingdoms, but also shows how those kingdoms influenced Europe and vice versa.

“One of the things we find most exciting about this project is when you’re in the presence of objects from the past, what a powerful experience that is,” says Kathleen Bickford Berzock, associate director of curatorial affairs at the Block. “These objects really put us as close as we can possibly come to knowing and touching a time that’s very, very distant from us and how that activates our ability to imagine and understand a time.”

Below are a few selections from the upcoming exhibit.

Biconical Bead, circa 10th-11th century

These beads were created as jewelry by artisans from the Fatimid dynasty. Their power stretched from North Africa all the way to the Hejaz, in what is now Saudi Arabia. With their capital in Cairo, the dynasty was a close trading partner with the Byzantine Empire, a relationship that influenced the design of Fatimid jewelry.

The Crucifixion, circa 1350–59

This religious scene was part of a portable triptych. The artist utilized gold-leaf stenciling techniques to mimic the texture of chainmail worn by soldiers. It’s an example of how gold from West Africa was being used widely across the Mediterranean and Europe, says Berzock.

Page From the “Blue” Qur’an, circa 9th-10th century

The Kufic script on this indigo-dyed parchment was written in gold, a technique called chrysography. It’s possible that this style was directly inspired by the illuminated manuscripts of the Byzantine Empire. It also resembles decorations on the mihrab (a niche in the wall of a mosque that indicates the direction of prayer) at the Great Mosque of Cordoba, Spain.

Virgin and Child, circa 1275–1300

This Virgin and Child statue, carved from ivory, hails from the Gothic period in France. According to the museum, the carving could only have been made from the tusk of an elephant roaming the Savannah. This coincides with a resurgence in ivory sculpting in Italy and France, says Berzock. The details here were also finished with gold.

Tada Figure in Style of Ife, circa 13th-14th century

Created in the Ife kingdom of southwestern Nigeria, this figure was important to spirituality in Tada, a small village located within the kingdom. It is likely that the raw copper from which it was crafted originated in France.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook