During the Renaissance, Drinking Wine Was a Fight Against Physics

Successful sips were signs of nobility.

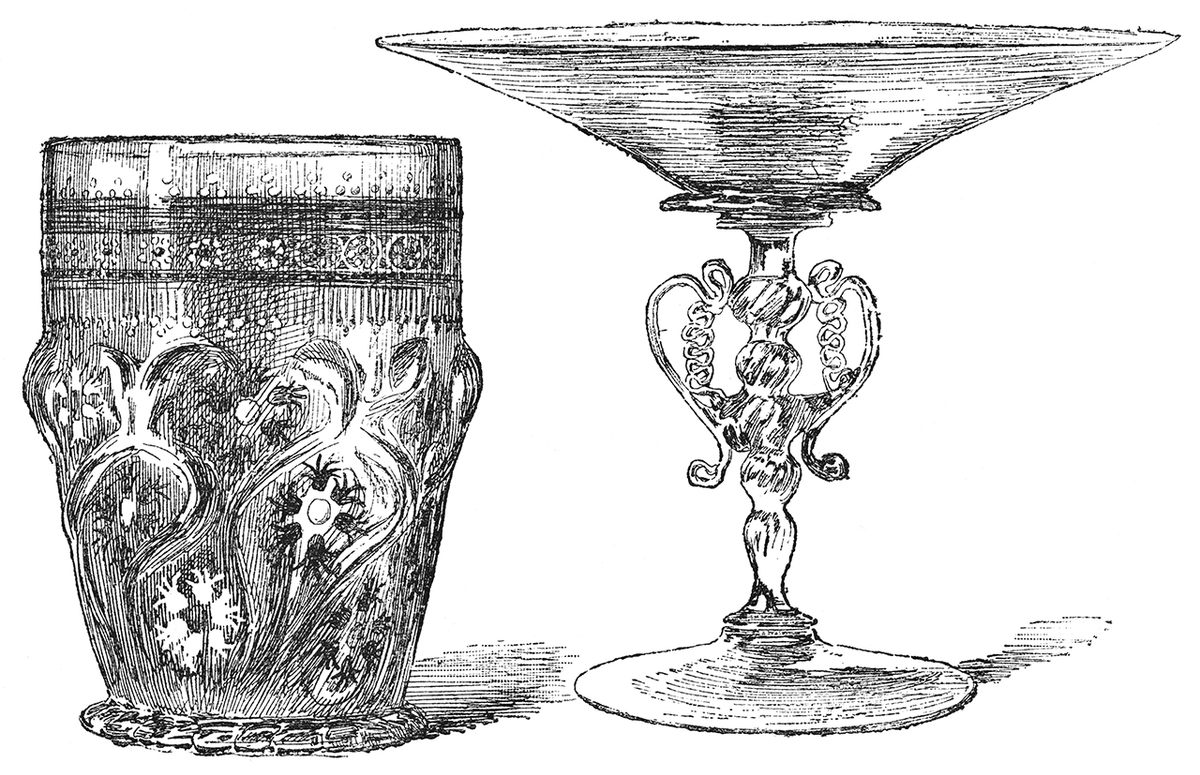

This isn’t a candy dish, or a cake stand. It’s a wine glass, circa 1600, from Venice, Italy.

If you attended a banquet at the house of an Italian lord, you’d be handed one of these, filled to the brim with red wine. You’d be expected to lift it by wrapping three fingers around the base, and raise it to your lips without spilling a drop. The whole process should look effortless.

Sound tough? The difficulty was the point. Courtiers were expected to embody the ideal of “sprezzatura,” a hard-to-translate word that combines the senses of elegance, sophistication, and nonchalance. In other words, you were supposed to be good at everything, without ever seeming to put any effort into it. What could be a better demonstration of sprezzatura than casually raising one of these sloshing, top-heavy goblets and taking a sip?

Even at the time, these bizarre glasses mystified visitors to Italy, such as the Englishman Richard Lassels, who wrote that “the Italians that love to drink leisurely, they have glasses that are almost as large and flat as silver plates, and almost as uneasy to drink out of.” But to those in the know, even subtle distinctions in how you held your glass could reveal your place in the social hierarchy. At least, that’s what the 17th-century artist Gerard de Lairesse implied in his best-selling manual for painters—he writes that a princess should be depicted “drawing warily and agreeably the little finger” from the glass, while her lady-in-waiting “fearful of spilling, holds the glass handily, yet less agreeably than the other.” The difference between royalty and mere gentility is the lift of a pinky.

These glasses were part of a cultural shift in dining that continues to shape how we eat. Until the 1500s, communal eating was the norm throughout Europe. Everyone, from princes to peasants, shared plates and glasses with their dining companions, and tucked in with their fingers. Etiquette manuals from the time advised readers to wipe their lips before sipping from the communal cup, and to avoid digging their hands too deep into the shared platter, lest they gross out their fellow diners.

But starting in the 1500s, Italian nobles began to lay out individual table settings for their guests. For the first time, each diner would be apportioned their own spoon, fork, knife, glass, and plate. This led to an abrupt shift in table manners. Suddenly, dining etiquette was less about common courtesy and more about demonstrating your sophistication. That’s where sprezzatura comes in.

In Renaissance Italy, dining was serious business. Nobles from different city-states cemented alliances by treating one another to lavish banquets, which required armies of specialized professionals to plan and prepare. During these feasts, courses were interspersed with live musical performances, and tables ornamented with massive, glittering sugar sculptures. The whole experience was a carefully orchestrated spectacle: the rich platters laid out on the credenza, the choreographed movement of plates in and out, the graceful lofting of each top-heavy glass.

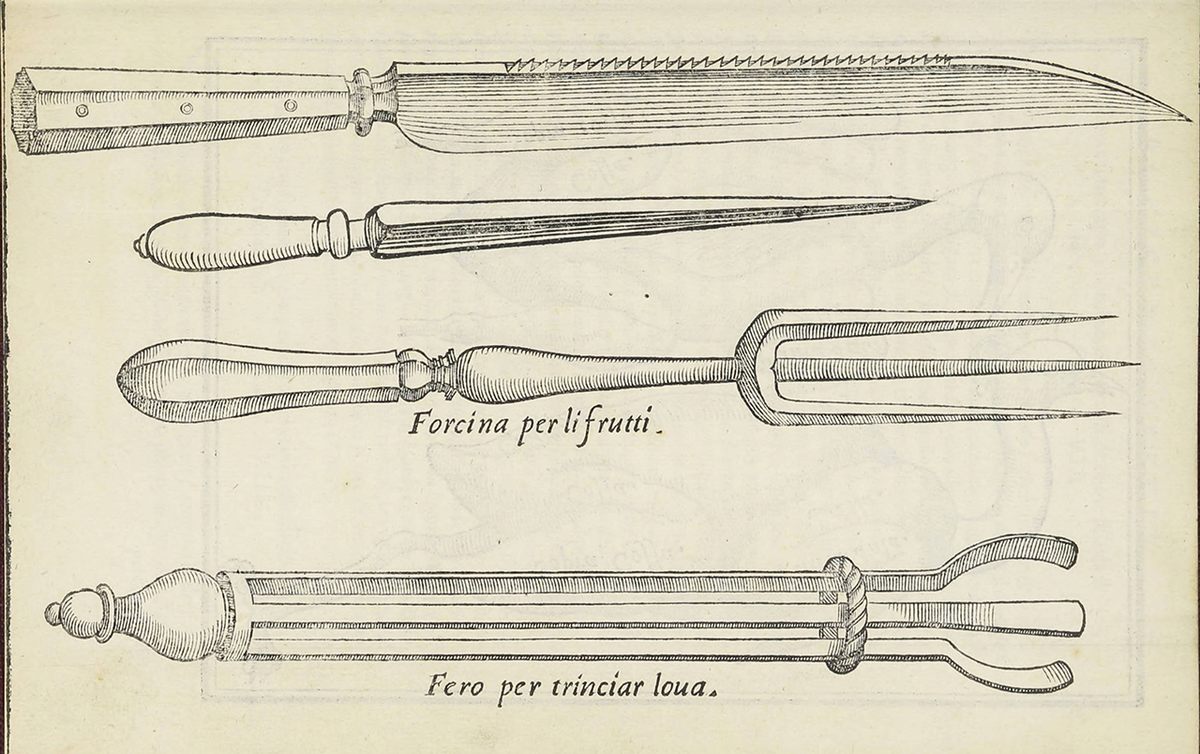

The servers were largely nobility themselves, young aristocrats serving as “officers of the mouth.” One of most important was the trinciante, or master carver. He would lift the meat into the air on a fork and carve it up so dexterously that perfectly portioned slices landed on each eater’s plate. Trincianti carved everything, from whole roast boars to tiny game birds and individual eggs, and seasoned each bite with a mound of salt balanced on the tip of their blade.

Then there was the cupbearer, whose role was to pour the wine, mix it with water, and serve it up in the shallow glasses. He also held up a candle to the glass as the drinker took their first sip, lighting up the wine like a gleaming ruby. Indeed, the goblets were considered to be just a half-step away from precious stones themselves. They were hand-blown Venetian cristallo, the first truly transparent glass ever made. Cristallo was incredibly expensive, and sometimes sold for 100 times the price of normal glass. Part of the reason elites valued it so highly was the common superstition that it would shatter instantly on contact with poison.

Many aspects of the banquet ceremony—the ritualized tasting of the dishes, the laying out of dishes on the credenza, the illumination of the wine in the goblet—were designed to reduce the risk of poisoning. Aristocrats had good reason not to trust their dining companions, as attested by the lethal levels of arsenic discovered in the bones of such Renaissance luminaries as Giovanni Pico della Mirandola and Angelo Poliziano. Perfect manners, after all, are a performance, and who knows what that performance might conceal? Certainly, courtiers were not as transparent as their glasses.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook