The Vanishing World of Neon Motel Signs

A photographer has spent decades capturing these symbols of Americana and the open road.

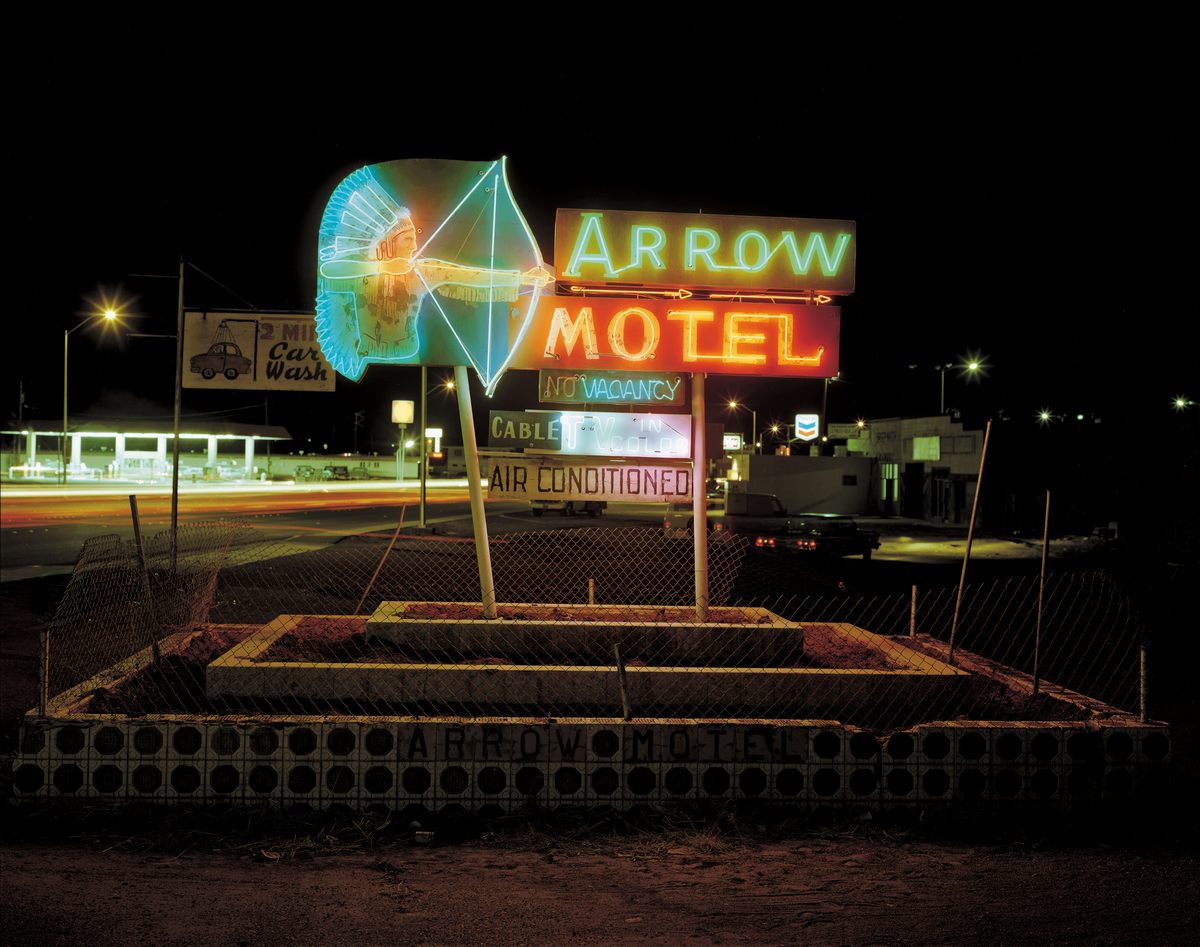

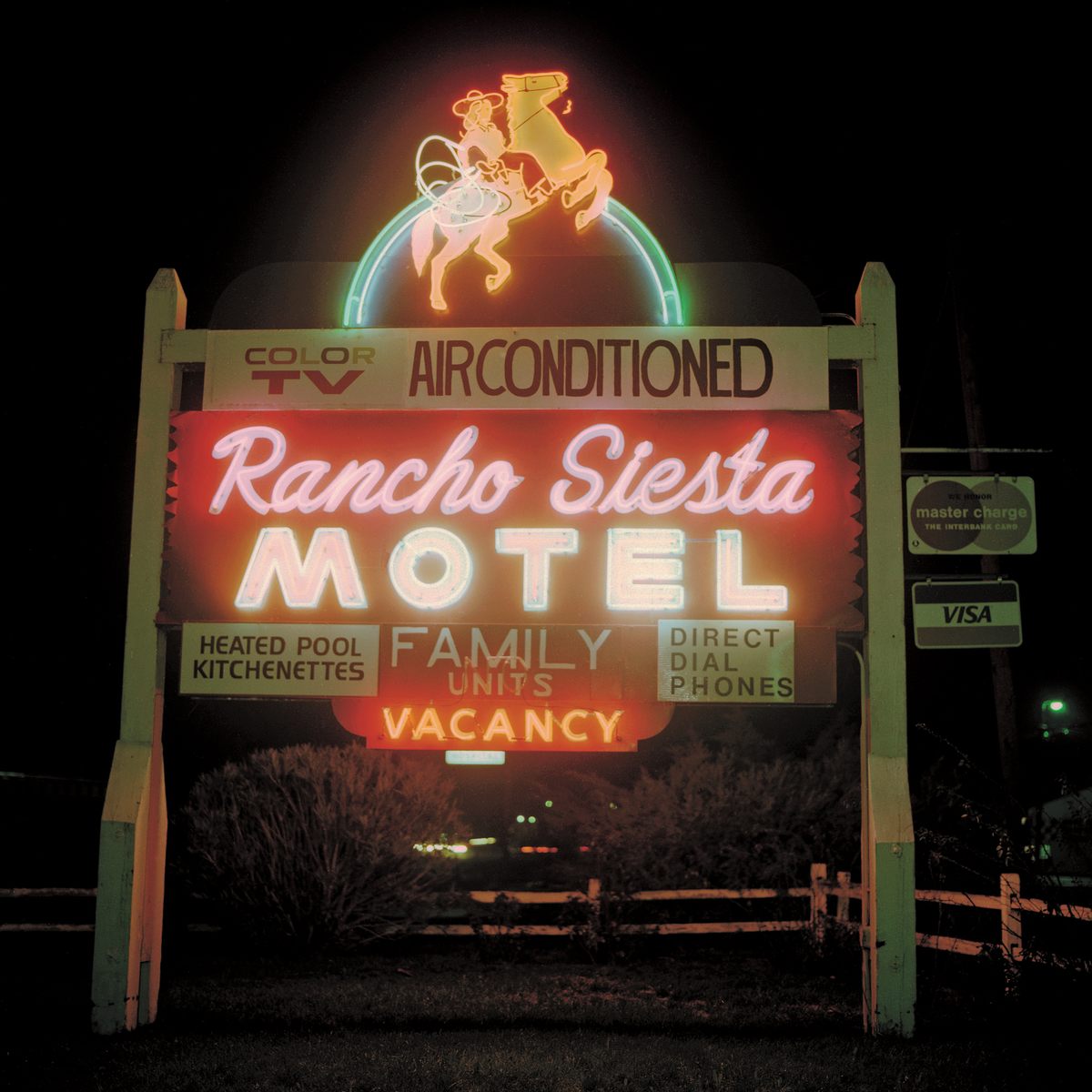

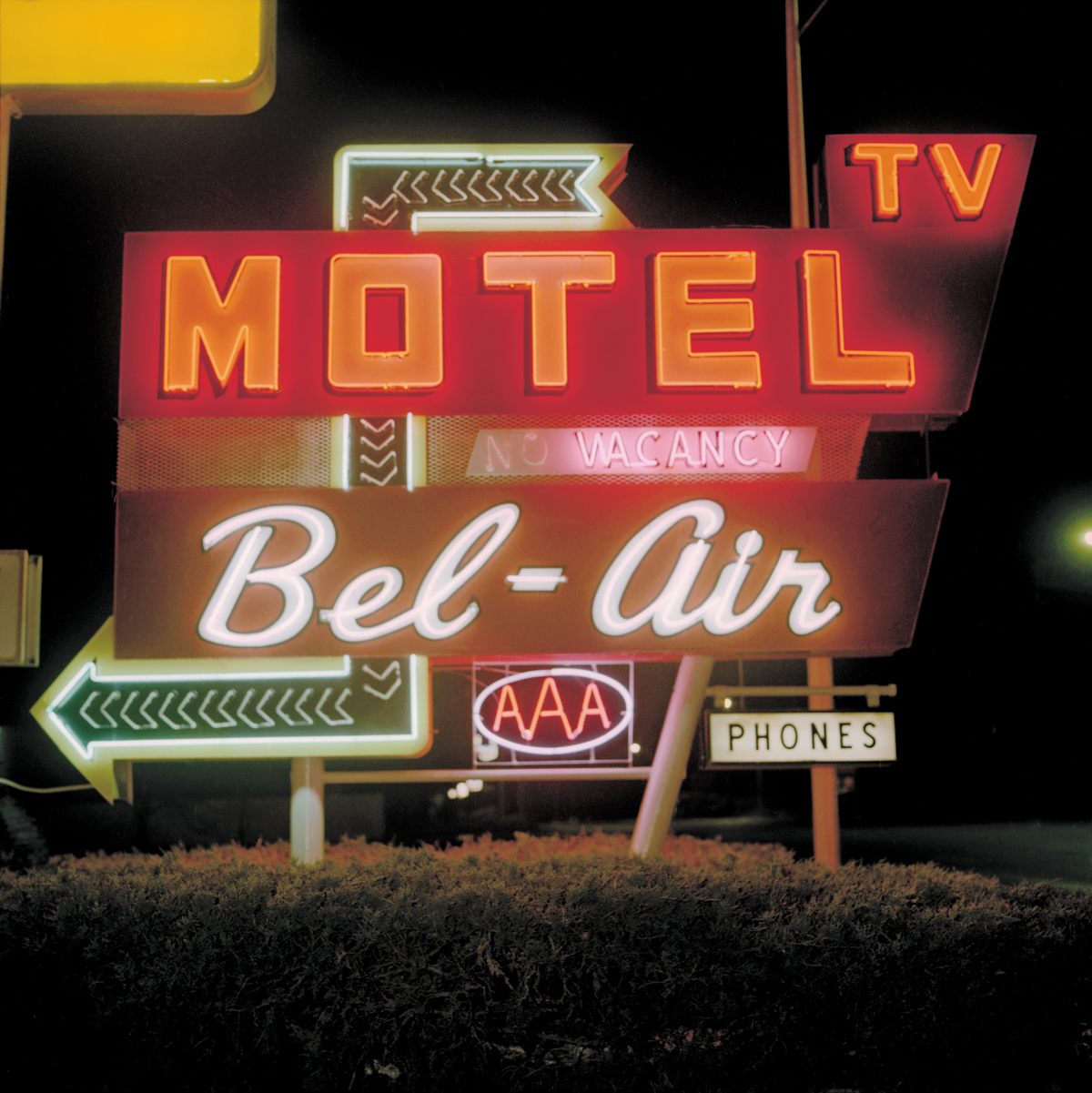

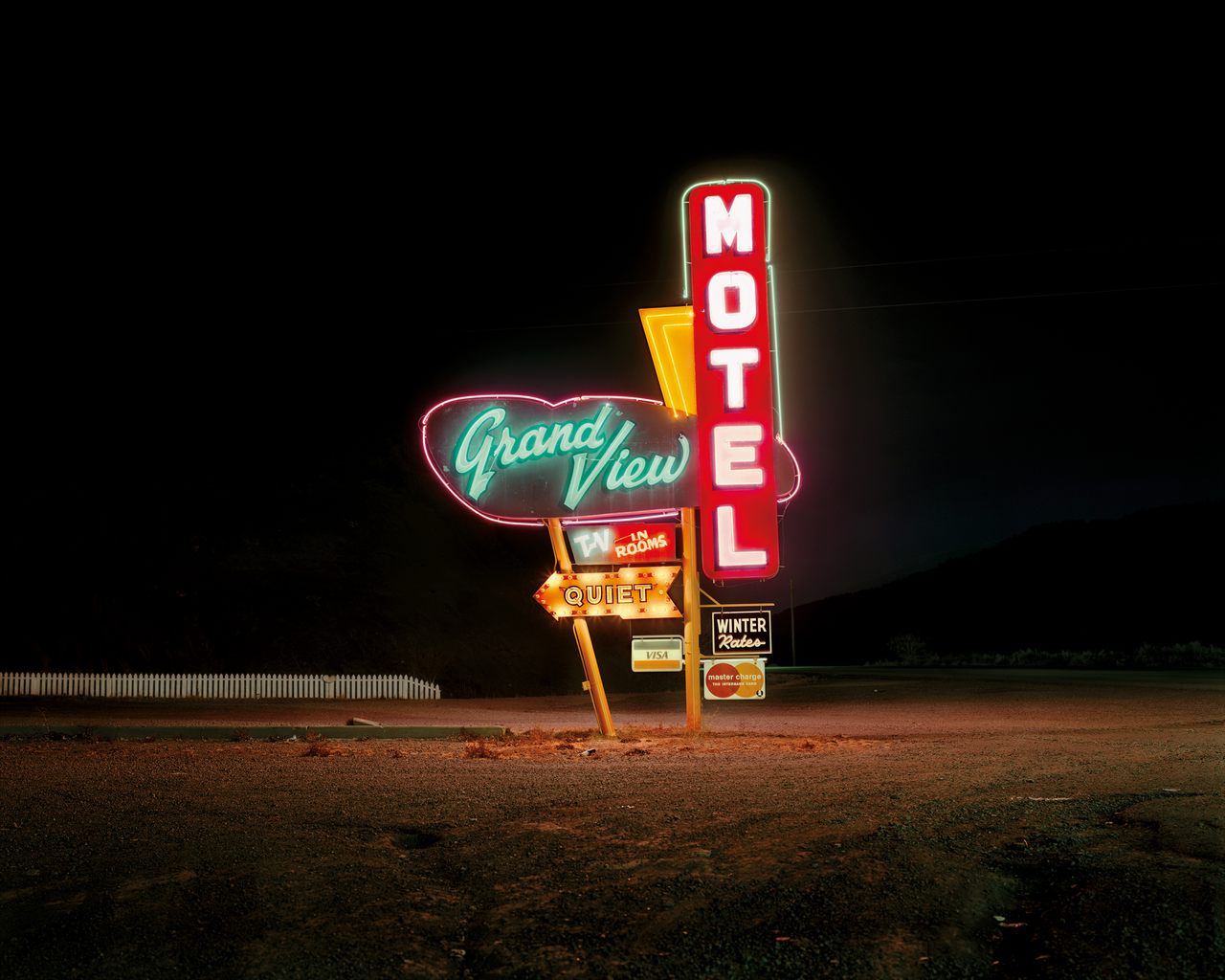

A distant glow appears on the edge of a desolate two-lane highway. As you pull up, the buzzing grows loud, drowning out the engine and the desert crickets outside. Voicelessly, it promises color TV, a kitchenette, and a phone in every room. Symbols of American expansionism and the Space Age, these iconic neon signs once topped countless motor lodges on Route 66 and other stretches of two-lane blacktop.

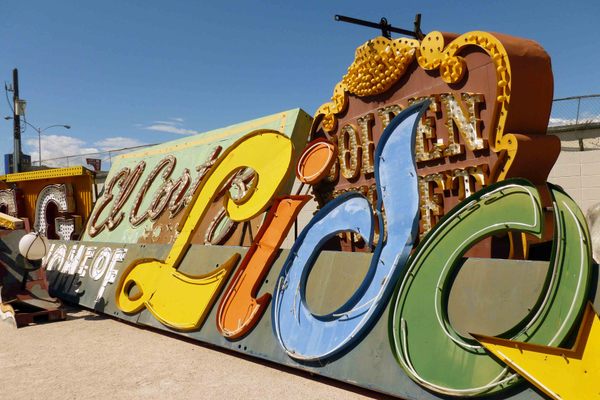

The rise of automobile culture at the end of World War II gave Americans an easy and affordable way to see the country. Subsequently, mom-and-pop motels began appearing to meet the demand created by these new travelers. The motels strove to differentiate themselves with kitschy themes and eye-catching neon signs, which eventually emerged as distinctive images of Americana.

Steve Fitch, who refers to himself as a visual folklorist, has documented the changing landscape of the American West since the mid-1970s. His new photo book, Vanishing Vernacular: Western Landmarks, is a striking visual commentary on how these once ubiquitous signs—alongside thousand-year-old petroglyphs, small-town murals, and drive-in theaters—are becoming part of the collective memory of the West.

Aside from his work as a photographer, Fitch also creates neon sculptures as an amateur neon bender. Atlas Obscura has a selection of images from his new book, and spoke to him about his interest in neon bending and his views on the changing landscape of the West.

What is it that appeals to you most about neon?

The way that you can draw with light.

What inspired you to work with neon, and how did you learn the craft?

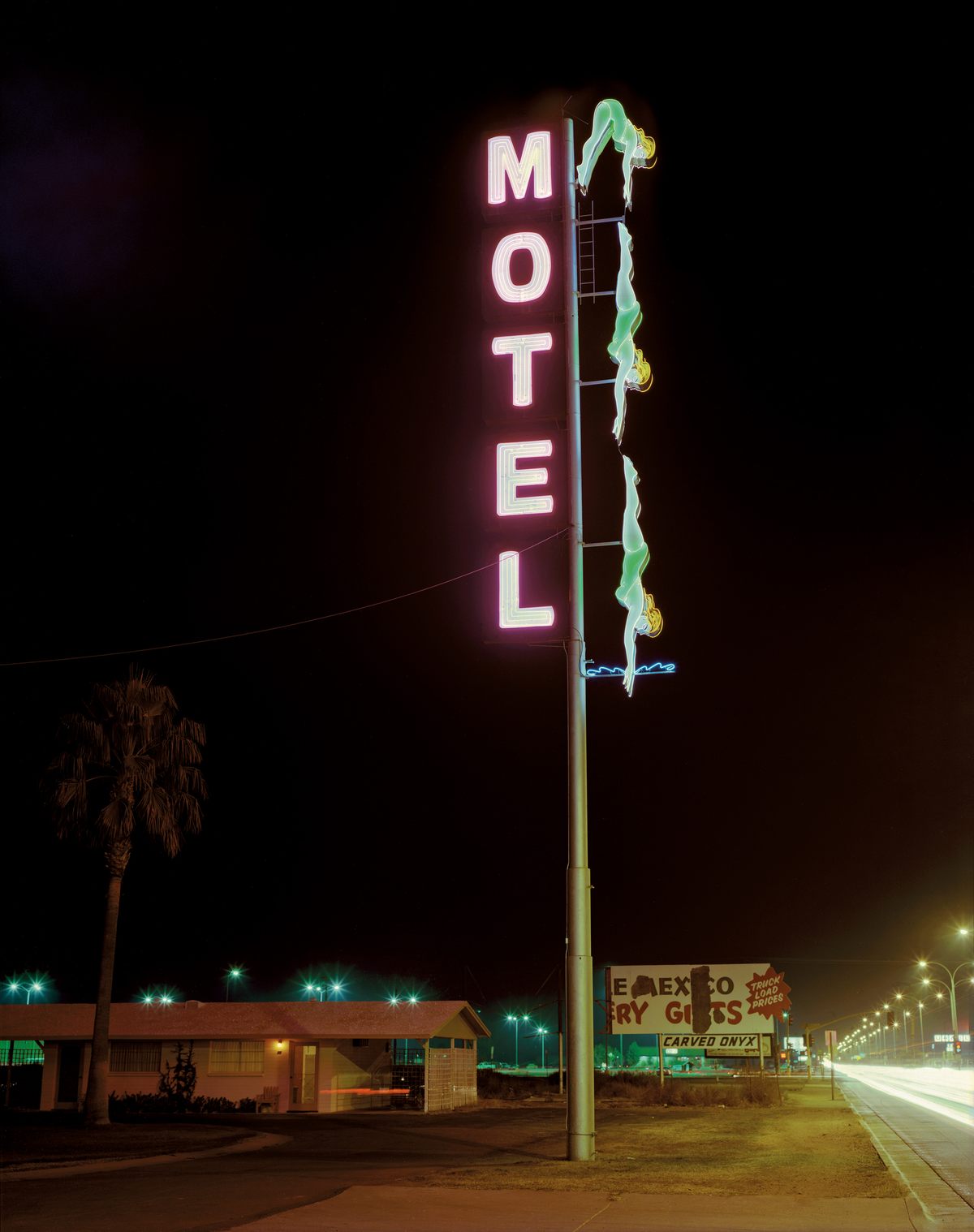

I became inspired to learn to bend neon because of the photography that I was doing in the early 1970s, photographing vintage neon signs along our highways. In 1972 I made my first night photograph of a motel in Deadwood, South Dakota, that had a neon clock in the window. I began to make more and more photographs at dusk and at night, and I became very attuned into the many striking neon signs and murals that adorned our landscape. There were many beautiful neon murals on drive-in theaters, as well as figurative neon signs at motels and restaurants, many of them animated.

Many of these photographs are in my first book, Diesels and Dinosaurs. I was so taken by the beauty of the material that I started to think about making my own neon art pieces, and decided that I needed to learn how to bend (i.e., “fabricate”) neon. At the time I was living in Berkeley, California, and would go to various sign companies in the Bay Area asking if they would teach me the craft. None of them were interested because at the time neon was dying out. When I moved to New Mexico in 1978 I encountered the same response. Then in 1981 I learned of a small neon school in Antigo, Wisconsin, that offered six-week, full-time courses in the skills needed to work with neon. The class I took was small, with only six students, and it got me started on the road to becoming a skilled neon bender. In 1982 I set up my own shop and began making my own neon artwork. It is a difficult craft and takes hours and hours of practice to become good.

How do you find places with neon signs to shoot?

Discovering neon signs or murals to photograph was simply a matter of spending a lot of time driving on our two-lane highways. I developed a sixth sense as to what roads might be good ones to explore. Cross-country highways like Route 66 were prime hunting grounds for interesting neon motel signs, and the state of Texas and the city of Los Angeles had many drive-in movie theaters with beautiful murals using neon. I was looking for neon signs or murals that were beautifully designed, well made, and that had a special flare or character to them. Often this meant that they related to their environment, such as neon cowboys in the West or animated neon Indians in the Southwest.

What are the special challenges of shooting neon signs?

It actually can be quite difficult to make a good photograph of a neon sign. I learned that working at dusk was usually the optimum time of day because you can show detail in the surrounding environment without the neon itself flaring out and becoming too bright. Because I am using a tripod and making long exposures, another difficulty can be all the commotion of the place, such as the streaks left by the lights of passing cars. I grew to appreciate the beauty of light at dusk, which is this charged time between day and night.

Do you have a favorite sign or photograph in this new collection?

That is a tough question because I like so many of the photographs. Perhaps I could pick the photograph of a motel off of Highway 287 [above], which to me is very melancholy, even sad and lonely. Or the photograph of the Greyhound Motel [below], which I find to be funny: a row of cacti measured against a neon line, almost like a police lineup of suspects.

What appeals to you about places like old truck stops, diners, and motor lodges?

When I was a kid in the 1950s, my family would make road trips from northern California to visit relatives on the family farm in South Dakota. We would stop at rock shops and dinosaur parks and eat in funky roadside diners and stay in neon-lit motels. What happened along the way, especially to a kid, was thrilling. Today, so much of our travel is on planes or interstates, where the excitement of exploration has been diminished or eliminated. What appeals to me about many of my subjects is the sheer folk inventiveness of so many of the signs and drive-ins. Many of the signs, for example, are not particularly sophisticated, but they are not ordinary, either. And, as I write in my book, they represent a pre-franchise and pre-interstate highway period, when there were many treasures to be discovered along our two-lane highways. The message they send, I think, is that the journey is as important as the arrival.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook