What Ancient DNA Can Tell Us About the Settlement of Vanuatu

A mismatch between genetics and language has baffled researchers for decades.

Around 3,000 years ago, humans came to shore on the archipelago of Vanuatu for the first time. An ancient seafaring people spilled out of their boats and onto the land, planted their feet in the white sand, and decided that these 83 islands, scattered across 800 miles of the Pacific Ocean, would be home. But who they were, and where they came from, has puzzled researchers. The islanders’ genetic ancestry suggests an origin point of what is now Papua New Guinea—but their Austronesian languages tell a different story, instead finding their roots in southeast Asia.

Now, however, two studies recently published in Current Biology and Nature Ecology & Evolution suggest possible backstories for these early settlers, using DNA sequences from the remains of around a dozen ancient inhabitants of Vanuatu and nearby islands.

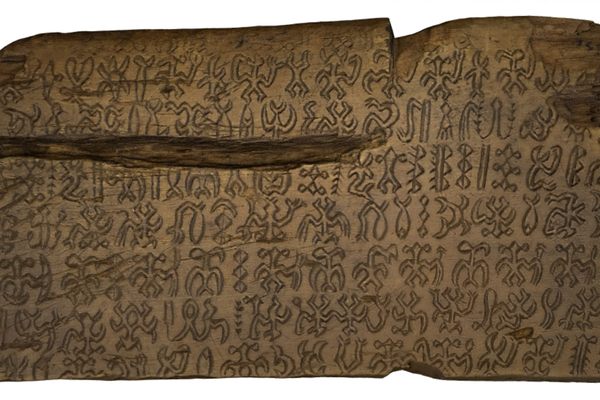

What seems near-certain, the studies agree, is that Vanuatu’s earliest settlers came from what is now Taiwan, a journey of over 4,000 miles. They were members of the Lapita culture who first left Taiwan around 5,000 years ago on specialized outrigger canoes that carried farming technology and Austronesian languages everywhere from Madagascar to Easter Island. Around 500 years after their arrival to Vanuatu, a group of mostly male voyagers joined them, coming from Papua New Guinea.

Where the studies differ is in assessing what happened next. Research published in Current Biology asserts that the Papuans eventually almost entirely replaced the original Vanuatuans, or pushed them out to far-off pockets of the archipelago. The team, led by Harvard Medical School geneticist David Reich, also found hints that there might have been multiple waves of migration from the larger islands around Indonesia and New Guinea—Papuan ancestry found in islands west of Vanuatu seem to have come from another source. “This is only the tip of the iceberg,” Reich told Nature.

Researchers behind the Nature Ecology & Evolution study, however, think it’s far more likely that the people gradually mixed with one another. “There wasn’t this huge boom, and the Papuans came in and killed off everyone,” anthropologist Heidi Colleran, from the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, told Nature. Many of Vanuatu’s 130 languages appear to be Austronesian in origin—though some researchers say that particular aspects, including what’s known as a bilabial trill (a kind of “bwwww” noise in the middle of some words), are distinctively Papuan—speaking to a kind of linguistic intermingling. But other linguists have pooh-poohed the suggestion and say it’s by no means a certainty that those features do originate in Papua New Guinea.

What scientists can agree on, however, is that right now, their studies are suffering from a paucity of data. Mark Stoneking, a geneticist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, told Nature that once more genomes for the region had been sequenced, it would be easier to fill in some of the blanks. As he said, “People tend to over-interpret things a little bit because it’s so exciting to have ancient DNA from this part of world.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook