The Struggle to Revive the Lost Native Language of Thanksgiving

Sometimes it is not easy to fulfill a prophecy.

Just a few decades ago, there were no living speakers of Wampanoag, the native tongue of the Cape Cod–based Mashpee Wampanoag tribe. (Their ancestors famously shared a meal with the Pilgrims, 400 years ago.) Then, in 1993, Jessie Little Doe Baird, who was then in her 20s, had a series of dreams about her ancestors, she told Yankee magazine. They were speaking to her, but she couldn’t understand them. A prophecy known to the tribe said that their lost language would come back when they were ready for it, revived by the children of those who had broken the language cycle. Baird saw the dreams as a sign.

Glimmers of Wampanoag are still visible in words that made their way into English. From its pohpokun, there is pumpkin. Moccasin comes from mahkus, skunk from sukok, and Massachusetts from masachoosut (“the place of the foothill”). But the wider language had been lost.

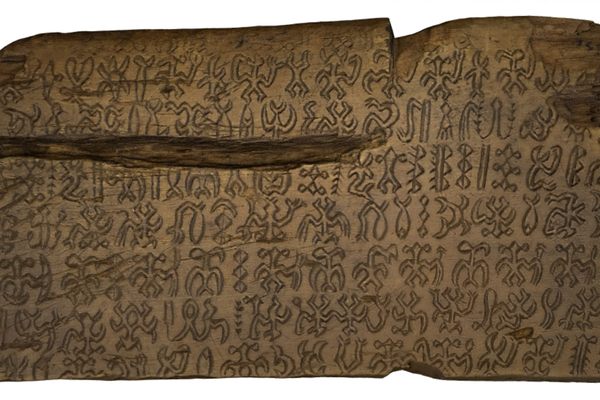

The journey to reviving Wampanoag was long and difficult—Baird had no formal training in linguistics, and there were no living speakers of the language. But historical documents such as A Key Into the Language of America (1643), a translated Bible and psalter (1663 and 1709), and the 1720 Indian Primer helped her begin to fill in the blanks. Baird’s ancestors had embraced literacy, and left reams of letters and documents. In 1903, philologist James Hammond Trumbull had put together a rudimentary dictionary to the language, which, she wrote, “leaves much to be desired [but] has been vital to the overall work of this grammar.”

At times, the challenge seemed insurmountable, but she was spurred on by her work with Kenneth Hale, her thesis advisor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, an expert in indigenous languages, and a direct descendant of colonizer and Rhode Island founder Roger Williams. She also collaborated with members of her tribe and other Native Americans to hammer out the intricacies of pronunciation, in part by looking to related Algonquian languages, which are still spoken today.

She published her thesis, An Introduction to Wampanoag Grammar, in 2000. In a foreword, she writes, to the members of her tribe:

The language was in the blood and bones of your People since the creation of your People. You have been nurtured from the land to which your People’s bodies returned. The language is now in your blood, bones, and your spirit. The language is itself a powerful spirit. It waits in a quiet way for you to return.

In the years since, Baird has put together a 10,000-word dictionary, received a MacArthur Fellowship, and helped launch the Makayuhsak Weekuw, or Children’s House, an immersion school that teaches 19 Wampanoag children the language. It’s hoped that many of them will be fully bilingual and, in decades to come, teach their own children. Baird’s own 13-year-old daughter, Mae Alice, is the first person in many generations to speak Wampanoag from birth. For the first time in well over a century, Wampanoag people are speaking their own language, in the classroom, at home, around the dinner table—and on the fourth Thursday of November.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook