Want To Become An Astronaut? Applications Open In a Week

Astronauts Neil Armstrong and David Scott. (Photo: SDASM Archives/flickr)

If you ask kids “what do you want to do when you grow up?” many of them will answer “an astronaut!” The dreamy wonder of exploring outer space, floating in zero gravity, and eating freeze-dried ice cream is tempting–even more so now, thanks to NASA’s highly-publicized ambitious goal of sending astronauts to Mars by the 2030s.

Now, for a very select group of people, that dream can be real. For the first time in three years, beginning on December 14, NASA will be accepting applications for entrance into its Astronaut Candidate Program. While the standards will be high and the competition fierce, candidacy will be open to all, setting the stage for perhaps the biggest astronaut class NASA has ever seen.

But what exactly does it take to have the “right stuff” in today’s era of space exploration? How does one become a 21st century astronaut?

The “vomit comet”: astronauts in simulated weightless flight in C-131 aircraft flying “zero-g” trajectory at Wright Air Development Center, 1959. (Photo: NASA on The Commons/flickr)

The basic qualifications to be an 21st century astronaut are actually quite democratic. You need a bachelor’s degree from an accredited institution (which covers about 2,500 American universities) in engineering, biological science, physical science, or mathematics. You must be between five feet, two inches and six feet, three inches tall, which includes about 95% of American men and 75% of American women.

Experience is required, but that qualification also leaves the door open for many; NASA defines “experience” as either a thousand hours of pilot-in-command time, or (more relevant for most) three years of professional experience–which ranges from getting a Ph.D. to being a K–12 teacher (of which there are over three million in the country).

Candidates also need to be able to pass NASA’s astronaut physical, which is similar to a military flight physical. This includes having correctable 20/20 vision (LASIK or PRK surgery are allowed, provided at least one year has passed since the procedure) and blood pressure that does not exceed 140/90 (which is the mark for high blood pressure). Finally, you must be a United States citizen.

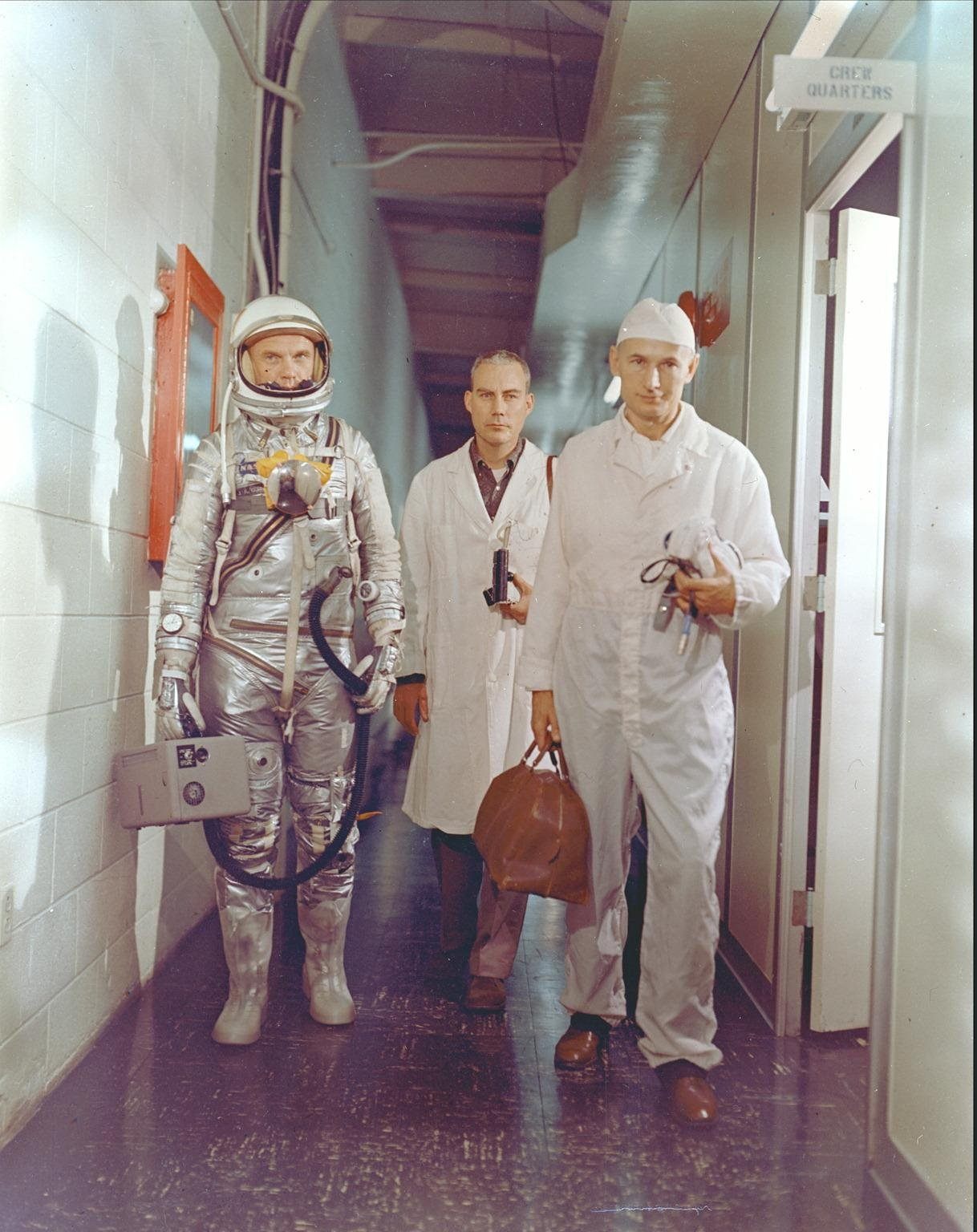

Astronaut John H. Glenn Jr., NASA flight surgeon William Douglas and equipment specialist Joseph W. Schmidt leave crew quarters prior to the Mercury-Atlas 6 mission, 1962. (Photo: NASA on The Commons/flickr)

These basic qualifications are not particularly stringent, which is why 2013’s candidate search (the last time NASA put a call out for astronauts) brought in over 6,000 applications, three times the previous average.

Johnson Space Center public affairs officer Nicole Cloutier-Lemasters told Atlas Obscura that she believes that there may even be more applicants this time around. Her prediction is based on the agency’s aggressive social media campaign, a flood of recent space-related movies, and NASA’s Mars goal.

“Just speaking anecdotally, I’ve gotten a lot more queries this time around from both media and public about the candidate program,” says Cloutier-Lemasters. “In general, I think there is an enormous excitement about traveling to a new destination… Mars.”

Astronauts Kathryn D. Sullivan, left, and Sally K. Ride display a”bag of worms”, a sleep restraint consisting of clamps, a bungee cord and velcro strips, 1984. (Photo: NASA on The Commons/flickr)

That’s what makes this astronaut candidate selection different than the ones that took place during the Space Shuttle program. The missions will go beyond the moon to explore asteroids, deep space, and Mars. As it was for the first space-age explorers, this is uncharted territory for humans. Despite images and rovers, there are still many unknowns about what astronauts will face on Mars when they get there.

In a recent press release, NASA administrator Charles Bolden said: “This next group of American space explorers will inspire the Mars generation to reach for new heights, and help us realize the goal of putting boot prints on the Red Planet.”

What we do know about Mars is that the atmosphere is 100 times thinner than Earth’s, it has intense continent-sized dust storms that can last for weeks, it’s about 200 times further from Earth than the Moon, and the average temperature is 80 degrees below zero. In addition, thanks to NASA’s recent announcement, we also know there’s water on the Red Planet.

Astronaut Mae Jemison onboard the Space Shuttle Endeavourm 1992. (Photo: NASA on The Commons/flickr)

All of this makes Mars a scientifically thrilling, unpredictable, and extremely dangerous place. The new astronauts may be must be prepared for extreme conditions, long travel times, and pressure-packed situations. Luckily, many on NASA’s selection committee, like Rex Walheim, know what it takes.

During his 20 years as a NASA astronaut, Walheim has gone to space three times and performed five spacewalks at the International Space Station. As a veteran astronaut, he’s had a hand in picking the last two classes of space explorers, including interviewing candidates in 2009. He says that beyond the basic qualifications, the selection committee looks to see how candidates can deal with a fast-paced environment, pressure-packed situations, and making quick decisions.

While they obviously look at on-the-job performance, they also like to know what candidates do in their spare time. “Maybe it’s some extra-curricular hobby they do that demonstrate that they can handle adversity or difficult situations… like perhaps being a mountain guide or world-class athlete,” says Walheim.

In this underwater group portrait, eleven SCUBA-equipped divers pose with the three astronauts, 1992. (Photo: NASA on The Commons/flickr)

One of the biggest differences between being an astronaut 50 years ago and today is that the missions are now substantially longer. While Space Shuttle missions were about two weeks, missions to the ISS and, eventually, Mars could take up to a year. Therefore, it is crucial not only to find candidates who can work in the isolation of space for a long periods of time, but to select for people who are good teammates. “Problems that may be an annoyance on a two-week mission, could be a real big problem on a six month or year mission,” says Walheim.

In addition, the further a space vehicle gets from Earth, the harder it gets to communicate with mission control. With previous Mars rovers, it took on average 20 minutes for a signal to get back to Earth (compared to the Moon’s average of about two seconds).

But like astronauts of yesteryear–Buzz Aldrin, John Glenn, and Sally Ride–this next class has the potential to make history. After all, these people may be the ones that will take that one small step onto Mars. Walheim notes that this puts a lot of importance on what the selection committee is doing: “I mean, we could be picking the next Neil Armstrong here.”

Backdropped against clouds 130 nautical miles below, astronaut Mark C. Lee floats freely, 1994. (Photo: NASA on The Commons/flickr)

Overall, the astronaut selection process takes about 18 months, with the 2015 class scheduled to be announced in June 2017. It is a long and arduous process, punctuated by medical exams, interviews, and lots of waiting.

However, Walheim says it’s well worth it for experiences like his last spacewalk:

It is a beautiful day and here comes the coast of California. We are flying right over San Francisco and the shape of the Bay is unmistakable. And you can see up and down the coast for hundreds and hundreds of miles… Just for a second, I watched as the coast came underneath me at 17,500 miles an hour, but 200 miles up it was a graceful transition.... it was truly spectacular.”

Soon, a new class of 21st century astronauts will be given the chance to see such sights. Perhaps they will even make history and become the first humans ever to put their boot prints on Mars.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook