The Politics of Pie Cutting at West Point’s Mess Hall

Or, why United States Military Academy cadets fear pastry.

Until the mid-1990s, squared-away plebes (what they call “freshmen who have their s**t together” at the United States Military Academy—better known as West Point—located some 60 miles up the Hudson River from Manhattan) carried a circular piece of paper in two small Zip-Lock plastic bags under their hats whenever the mess hall was serving pie. They always knew when pie would be on the menu because they always knew when everything was on the menu; part of their job as the punching bags of the United States’s finest military academy was to know what was for lunch.

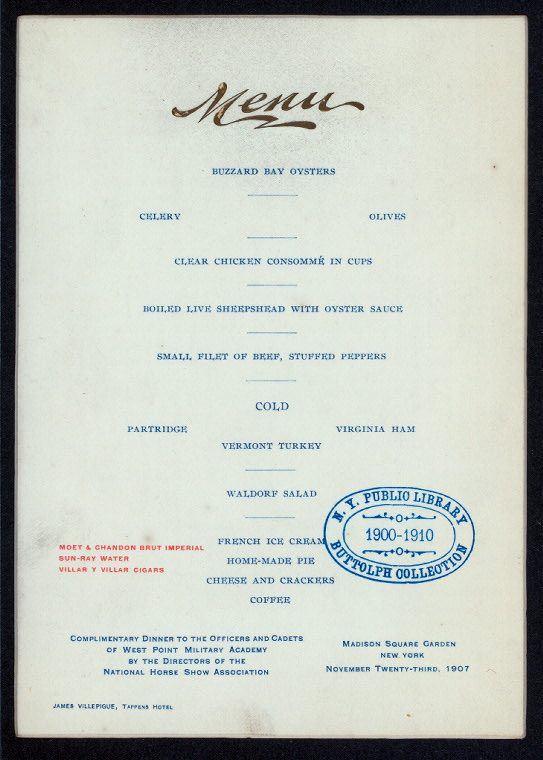

The monthly menu at Washington Mess Hall, West Point’s dining facility, was part of “plebe knowledge,” the truckload of information plebes had to rattle off from memory at the request of any upper-class cadet. This was known as the “fourth-class system,” and in their first year of the four-year program, plebes were its fourth-class citizens. Along with menus, plebes also had to memorize West Point history, news headlines, and interesting trivia questions. Failure to produce any of the required knowledge on the spot exposed these greenest of West Pointers to the wrath of their older classmates, and to any number of physical or verbal humiliations. So plebes pored over paper printouts of each month’s meals, posted the menus to their doors as ever-present reminders, and quizzed each other on what they would eat next Tuesday lunch, or for dinner the following Thursday.

And each month, plebes would take particular note of what nights there would be pie. Those evenings, they’d stash their double Zip-Lock-covered piece of paper in their hat, cross their fingers hard, and hope they wouldn’t have cause to retrieve it.

The food at West Point has, traditionally, not been very good. A Senate inquiry in 1860 concluded that the fare served to the corps of United States Army officers-in-training “was neither nutritious nor wholesome, neither sufficient nor nicely dressed.” “Sometimes the meat is almost rotten,” cadets told the Senate investigators. “Bugs will be found in the sugar, and cockroaches in the soup.”

For these early generations of cadets, at least there was pie. Whether served in the cadet mess hall or by professors’ sympathetic spouses, pie provided much-needed calories, a reminder of home, and a balm to soothe the life of hard training and even harder hazing they endured. In addition to their academic courses, cadets took (and still take) physically demanding classes such as boxing, gymnastics, and swimming, and are expected to complete long marches, obstacle courses, and regular fitness tests. (Despite these physical demands, cadets throughout the 19th century reported that bread was the only other reliably edible food.)

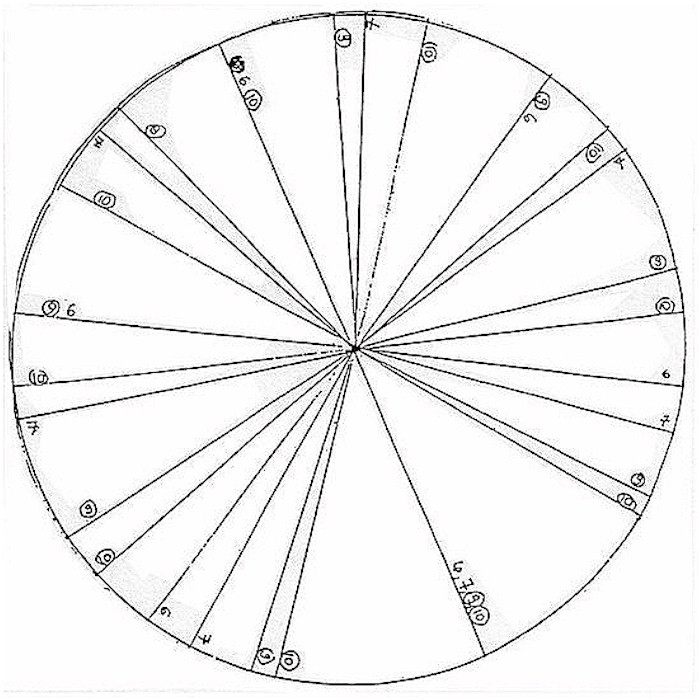

More recently, though, pie at West Point lost its innocence. For cadets who passed through the Academy in the later decades of the 20th century, a favorite form of hazing centered on pie. At dinner in the mess hall, plebes were made to cut the dessert into a mathematically impossible number of exactly equal slices: seven, nine, or 11. Upperclassmen looked on, taunting. The Zip-Locks under plebes’ hats? They held pie-cutting templates—literal pie charts—that helped plebes cut perfect slices and, most importantly, avoid their elders’ wrath.

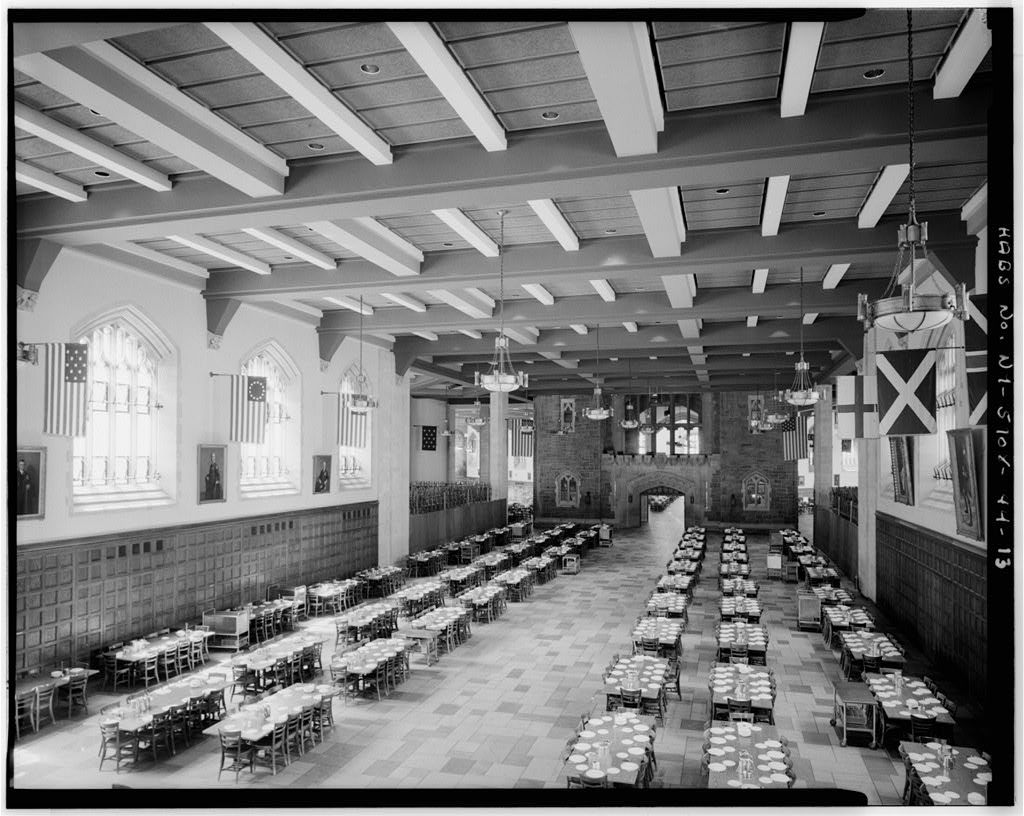

In those days, plebes had much to fear from Washington Mess Hall, the cavernous stone building where cadets ate, and still eat, their meals. For the unaffiliated, the “cadet mess” looks like a Hollywood set: one part Game of Thrones imposing, one part Harry Potter magical. The hall’s six wings stretch out from the central stone pedestal known as the poop deck (“poop” being the military’s appetizing word for information). Battle-torn flags adorn the two-story stone walls, and chandeliers in the shape of ornate candelabras hang from the cathedral ceilings. But for plebes, the mess hall has traditionally been less throne room, more prison cafeteria.

Since the late 1960s, when the mess hall was expanded to its current size, the corps of more than 4,000 cadets have filtered into the hall at mealtimes to find their seats at 10-person, mixed class tables. Then, for 20 excruciating, uninterrupted minutes, plebes were at the mercy of their older classmates.

Food at West Point has always been served family-style, and the plebes at each table are responsible for announcing its arrival (“Sir, the Brussels sprouts are on the table!”) and serving it. They rotate through roles like the “Cold Beverage Corporal” and “Hot Beverage Corporal,” whose roles are more or less self-explanatory, to the less aptly titled “Gunner.” Until the mid-1990s, the Gunner was the unlucky soul in charge of cutting the pie.

The squared-away plebe had a procedure when it was his turn as Gunner: remove the outside baggie (which presumably had touched his hair), place a sugar packet or piece of bread in the center of the pie to act as a riser, center the template on the packet so that it didn’t touch the pie, and score the pastry’s edges for the desired number of pieces. Then, remove the template and slice. Voila, perfectly cut pie.

It didn’t always go that well. A West Point urban legend involves a Gunner who announced, “Sir, the dessert for this meal is cherry pie,” and then took a knife to the pastry. After struggling for several minutes to cut the prescribed seven slices, he grabbed his spoon, stirred the pie vigorously, and amended his announcement. “Sir, the dessert for this meal is cherry cobbler!”

Creativity apparently kept that plebe out of trouble, but for most others, failure to achieve geometric perfection resulted in being yelled at or ordered to run laps around the poop deck. Sometimes, especially if it was bad weather, the offending plebe would be ordered to stand outside, freezing until the conclusion of the meal. The pie scars remain: West Point grads from that era, now 20 or more years from graduation, have been known to feign terror at being asked to cut a dessert.

Pie is still served in West Point’s cadet mess hall, though less often than it used to be. In recent years, budget cuts reduced the baking staff from 22 down to four, and they no longer have enough hands to roll out individual circles of dough for the 400 to 500 pies they need to serve the corps of cadets. Instead, they make cakes and bars, which are easier to mix in large batches. But the kitchen still bakes them in pie tins—they still look like pies.

These days, pie-shaped desserts come without the trauma. Hazing has been punishable by courts martial since 1874, but a Department of Defense report in 1992 found that “hazing-type behavior” was still prominent at West Point—and cited pie-cutting rituals as an example. In 1999, the institution officially banned hazing with pie or anything else. This was widely hailed as a good thing outside the Academy, and it definitely means plebes enjoy dessert more.

But for some “old grads” (the ones afraid of pastry), abandoning pie cutting rituals means that today’s cadets are missing out on something valuable. Being yelled at while cutting pie into an odd number of slices, they say, or the myriad other indignities of the fourth-class system, taught cadets how to complete a detail oriented, exacting task while stressed out and under pressure. For a member of West Point’s class of ’83, pie cutting “provided me with a priceless gift”: the ability to “sort through the mess, bring some order to it, and continue functioning.”

To be sure, there’s a lot more than pastry in West Point’s pies.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook