When the Government Banned PBR, Pabst Made Cheese Instead

Selling dairy products helped the brewery survive Prohibition.

In the early 1900s, Pabst was a paragon of success. What started in 1844 as a tiny Milwaukee brewery had become the largest beer maker in the nation by 1874, producing more than a million barrels a year in 1893. That same year, the company started claiming that one of its lagers had won a blue-ribbon award at the Chicago World’s Fair. It was pure malarkey. But the blue silk ribbons they tied around bottle necks put some prestige behind the brand, and helped turn the Pabst family into millionaires.

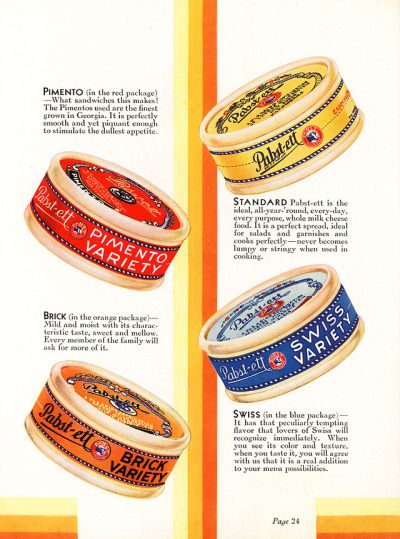

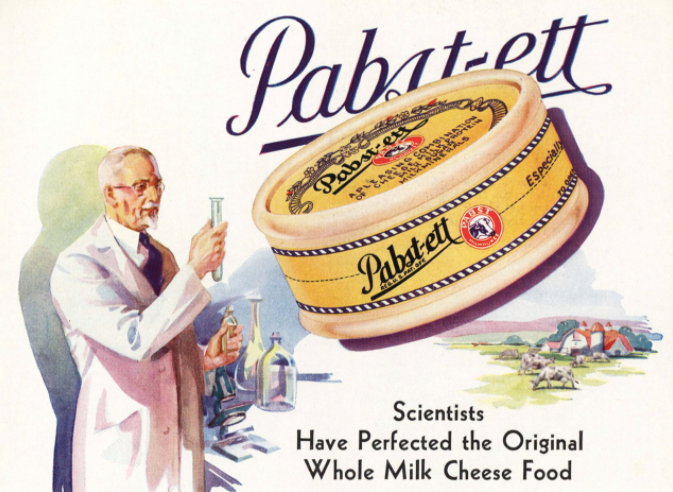

Yet as America moved towards Prohibition, the folks at Pabst recognized that their beer empire was about to dry up. So, soon after the nationwide ban on alcohol went into effect in 1920, Pabst pivoted to making a “delicious cheese food.” They called it Pabst-ett and sold it in block and spreadable forms, as well as in cheddar, pimento, and Swiss flavors.

This wasn’t the only side hustle the Pabst Brewing Company pursued in 13 years of prohibition, nor the most profitable of them. But it exemplifies the mindsets and tactics American brewers adopted to ride out the decade and resurge after 1933—something only a few dozen of the nearly 1,300 brewing companies active in the U.S. in 1916 managed to do.

According to beer historian Maureen Ogle, the key to survival for breweries during Prohibition was to realize that it wasn’t a passing political phase. Many brewers reportedly thought the country would break and revise the law after two or three years, and so took a deadly sit-and-wait approach. Brewers who chose to act had to find new ways of working with what they had on hand: their machines, supply chains, and expertise.

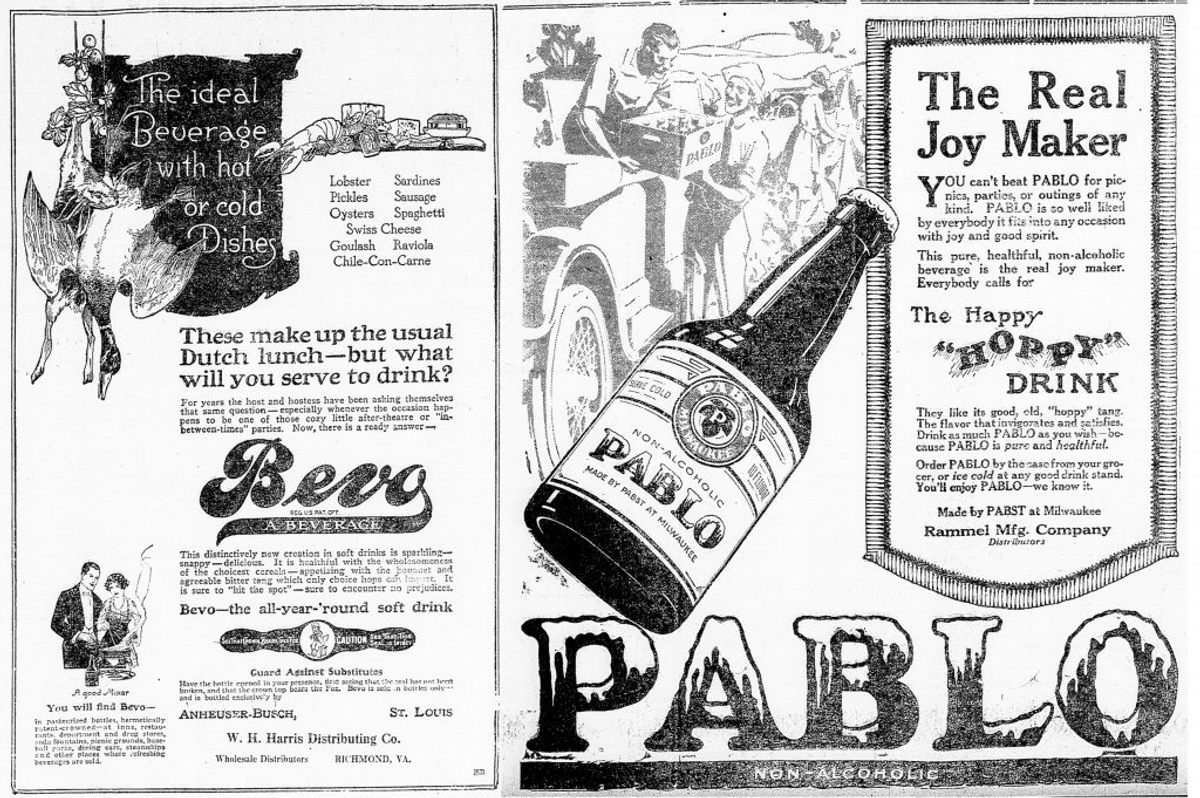

Thanks to a provision in the law behind Prohibition, which allowed the production of less than 0.5 percent alcoholic drinks, most breweries pivoted to making “near beers.” Anheuser Busch, whose co-founder Adolphus Busch was apparently wary of rising temperance movements and bracing for nationwide Prohibition as early as the 1890s, led the pack by promoting a near beer called Bevo in 1916. But every big name in American beer eventually had one: Miller had Vivo. Schlitz had Famo. Stroh’s had Lux-o. Yuengling had Juvo. And Pabst had Pablo. (At least six breweries received permission to brew beer as a medical product, including Narragansett, which apparently distributed a high-iron porter to hospitals as a tonic for pregnant women.)

A number of breweries started making alcohol-free soft drinks, too. Anheuser-Busch even experimented with carbonated coffee (Kaffo) and tea (Buschtee). “At one point,” Ogle notes, “Pabst studied the possibility of investing in artichoke juice.”

Yet while drinks like Bevo did well initially, advertising restrictions, market crowding, and the rise of massive bootlegging operations cut into near-beer and non-beer sales. Breweries also struggled to use their malt-making expertise to break into the already established candy-making world, or even to sell malt extracts as baking products. (To customers who clearly wanted to use them to home brew, much to the government’s consternation.) Business was bad enough that the Miller family tried to sell off their company in 1925, but found no buyers.

A few breweries got more creative. Coors tapped into the clay deposits near its facility to make ceramics, while Anheuser-Busch and others adapted their facilities to produce machine parts. The Busch family invested heavily in the 1920s in learning how to make and sell groceries—everything from infant formula to frozen eggs. Anheuser-Busch, as well as the Pittsburgh Brewery, Stroh’s, Yuengling, and a few others, realized their refrigeration and storage equipment could be parlayed into ice cream making and distribution to tap into rising demand for the frozen treat.

In the years leading up to Prohibition, the Pabst family had already dipped their toes into the dairy business. They’d initially acquired farmland in the late 1800s to raise French Percheron horses to haul their beer wagons, but as Ford’s Model-T cars started to displace equine labor in the 1910s, they swiftly shifted to rearing Holstein dairy cows. One of the family’s scions, Fred Pabst, Jr., seemed especially keen to expand the Pabsts’ agricultural interests. So when the company took stock of its assets just before 1920, it seemed logical to draw on its herds of dairy cows and brewery ice cellars to make cheese and other dairy products.

The Pabsts marketed Pabst-ett and other dairy products as “digestible” and hyped their industrial purity—a 1927 ad touted “pure Holstein milk from our tuberculosis-free herd”. The company released at least one cookbook for housewives, Recipes the Modern Pabst-ett Way, about the ease and splendor of working with their cheese spreads. And Pabst reportedly sold at least eight million pounds of the stuff during Prohibition. But Ogle suspects that this barely bolstered the company’s profits—although that’s hard to prove.

Instead, it caught the eye of the Kraft Cheese Company, which was founded in 1909 and had recently started consolidating the dairy industry through acquisitions. In 1923, Kraft acquired The Velveeta Cheese Company and its spreadable processed cheese. Seeing Pabst-ett, a later product, as a copycat, Kraft sued Pabst and won, although they reportedly gave the brewery a royalty-free license to keep making Pabst-ett. (No one I spoke to for this article was sure why they would have done that; a Kraft Heinz spokesperson said they had no information on Pabst-ett.)

In the end, Ogle argues, real estate rather than cheese spread got the Pabst family—and many other breweries, including Miller—through Prohibition. Like other brewing magnates, Fred’s father, Frederick Pabst, Sr., who led the company throughout the late 1800s, had snatched up hundreds of plots of land to build beer gardens, restaurants, and taverns that would serve and advertise Pabst. He also invested in multiple hotels, Milwaukee’s first skyscraper, and a Wisconsin resort. By 1893, 20 percent of the Pabst Brewing Company’s assets were reportedly in real estate, and by 1910 the family owned more than 400 plots in 187 cities. During Prohibition, they spun off a dedicated realty company to rent or sell those plots—even leasing their core brewery space to Harley-Davison. “They managed that well,” says Ogle, “earned good returns on it, and so had cash on hand in 1933 [when Prohibition ended] to rebuild their brewery.”

A few breweries that survived Prohibition kept their side hustles running, including Coors, which spun its ceramics business off into CoorsTek, a still extant company that at its peak was valued at more than $1 billion. Stroh’s and Yuengling kept their ice cream operations alive for decades, until Yuengling shuttered that side project in 1985 and Stroh’s sold off its ice cream brand in 1990. (It’s since bounced between owners.)

But Pabst snapped its attention back to beer above all else. The brand, Ogle argues, had always been primarily concerned with large-scale national markets and industrial innovations. So as the agriculturally-inclined Pabsts withdrew from the business (Fred, Jr., sold off the family’s controlling share in the company in 1933), its new managers likely didn’t see much point in competing with Kraft and other big dairy powers when they’d never mastered cheese retailing or wholesaling. (Pabst did not respond to a request for comment.) They sold Pabst-ett to Kraft (which may have continued to sell it into the 1940s, though its fate is wholly murky) and focused on developing beer-canning techniques and making strategic acquisitions.

In retrospect, that decision was a bit of a shame, because “low-brow” chefs have repeatedly proven that cheap cheese and Pabst Blue Ribbon (PBR), today the brand’s most famous beer, go together well in dishes such as PBR mac and cheese and PBR cheddar nuggets (served in a cut-up can).

But just because Pabst-ett vanished after Prohibition, that doesn’t mean it is necessarily gone for good. In 2014, Yuengling revived its ice cream brand; they did not respond to a request for comment, but this seems like a nostalgia move. And after ages spent being more brand than brewer—for decades, Pabst has paid Miller to make PBR, and other beer brands it has bought up—Pabst has slowly opened smaller-scale and more diverse operations, including a microbrewery and restaurant in its original Milwaukee location. Perhaps, with enough public interest, they might consider playing around with processed cheese again as well.

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook