What Does This Alien Minor Planet Look Like?

A peanut? Or maybe a bowling pin?

Faced with something alien, humans tend to grasp for something familiar. Ever since we started looking at the sky, we’ve seen our own image up there. Early moon-gazers mistook hardened lava for seas, because the dark ribbons reminded them of churning waves. Even now, science educators often compare distant features on other planets or moons to the peaks and valleys that Earthlings have seen up close. “The trouble we normally have with space is, if we try to understand something, we only have one example—our own planet,” Colin Stuart, a fellow at the Royal Astronomical Society and author of the book How to Live in Space: Everything You Need to Know for the Not-So-Distant Future, told me last year. “We always try to compare things to Earth when we can. If you’re starting with something they know about, you’re not starting from the beginning.”

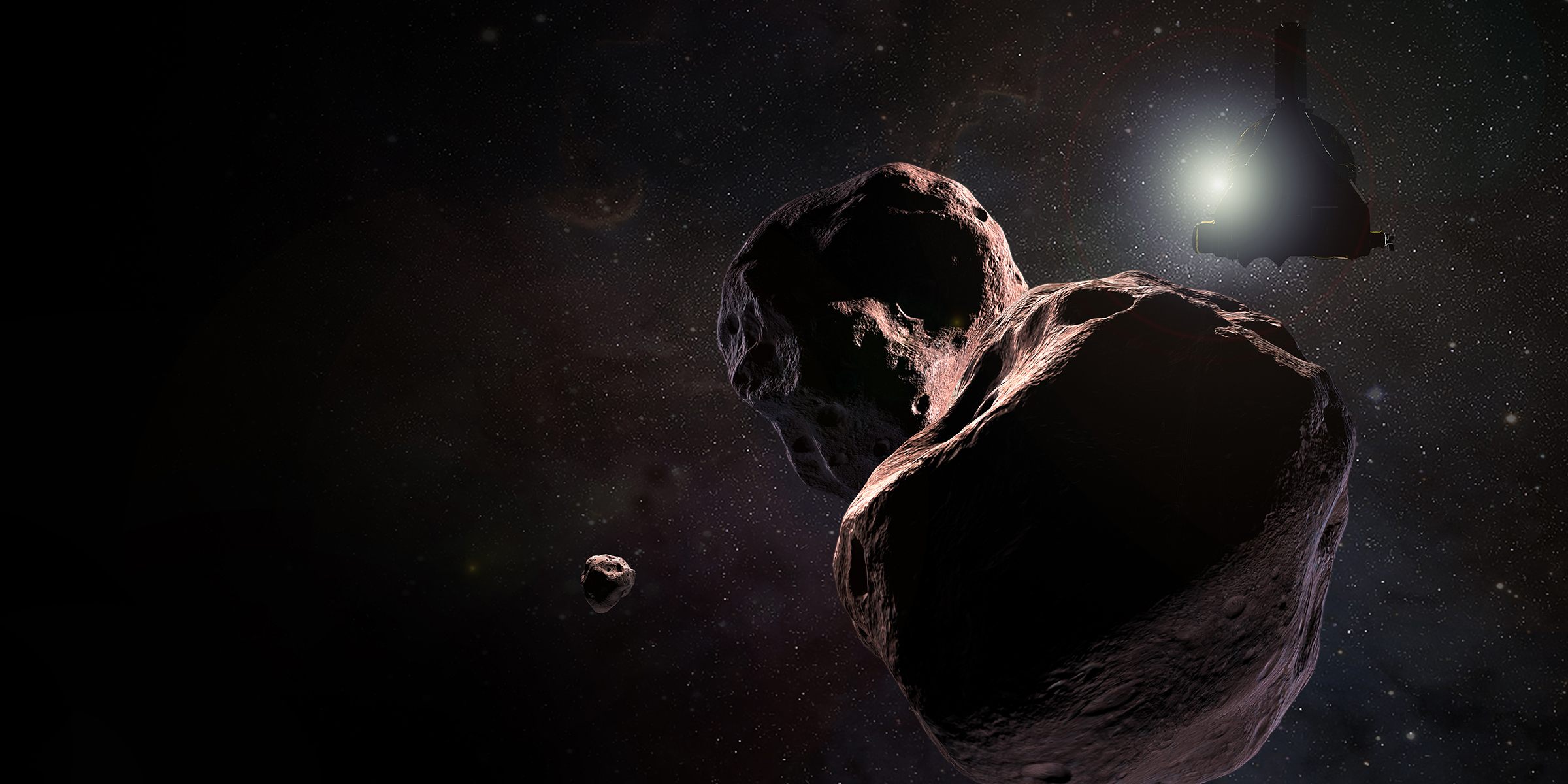

All of which is to say that it was no surprise that, when NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft hurtled by the distant minor planet known as Ultima Thule and 2014 MU69 on New Year’s, people following along on Earth reached for descriptions that felt relatable.

The whole scenario was anything but. To approach the far-off object, New Horizons trekked deep into the cold, rocky Kuiper Belt, which is freckled with asteroids and other fragments left over from the birth of our solar system billions of years ago. Scientists hope that by getting close—or at least close-ish—to this “pristine specimen,” which they suspect remains fairly unchanged since it formed, they can gain new insight into the origins of the planets. This flyby brought the spacecraft within 2,200 miles of 2014 MU69, whose name is a reference to the date when it was first recorded by scientists. The craft sped four billion miles from Earth, and far beyond Pluto.

Since the time-stamped name is a mouthful, the New Horizons team nicknamed the target “Ultima Thule,” borrowing from ancient shorthand for a beguiling, far-off realm. The moniker is possibly temporary, because the team will prepare a formal submission to the International Astronomical Union, which oversees the names of celestial bodies. But its long history stretches back to Greek and Roman cartography, in which “Thule” referred to the northernmost location. By the medieval period, it conjured anything at the fringe of the known world. In 1539, the cartographer Olaus Magnus labeled it on his Carta marina, the first detailed map of the Nordic lands. (Here, it’s an island flanked by fabulous, sea-faring beasts.) The name was variously used to refer to places including Iceland, Greenland, and Norway, and it’s also the current name of the U.S. Air Force’s northernmost base, in Greenland, several hundred miles above the Arctic Circle.

Though Virgil coined the poetic variation “Ultima Thule” thousands of years ago, as Meghan Bartels reported for Newsweek, the phrase was eventually commandeered by the Nazis. More recently, it has been used to describe everything from remote reaches of caves to scattered lands that are far-away and freezing, including Siberia and an Alaskan lodge that is “a hundred miles from paved roads.”

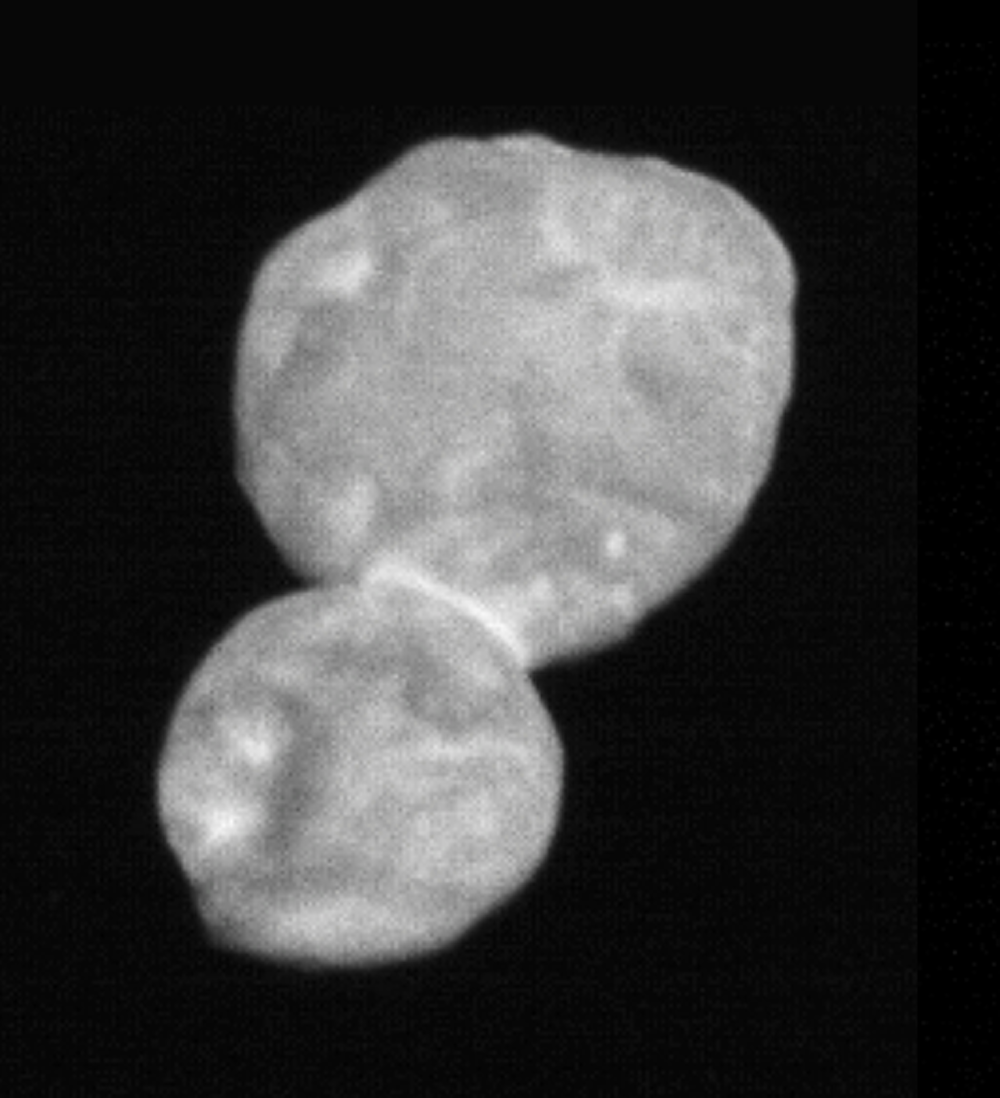

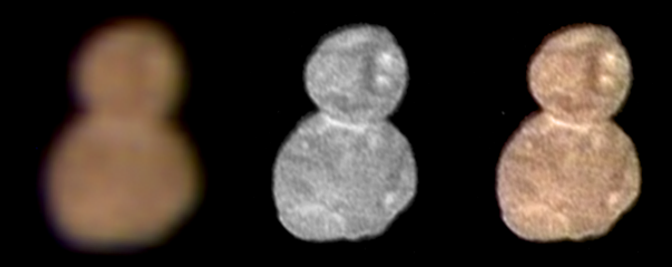

This cosmic Ultima Thule is actually two objects, fused together—one lobe slightly larger than the other. The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory reports that the formation may have happened when the two bodies collided fairly gently, “no faster than two cars in a fender-bender.” The mission team dubbed the larger portion, which measures roughly 12 miles across, “Ultima,” and its smaller twin “Thule.” Alan Stern, of the Southwest Research Institute and a principal investigator for the recent mission, defended the nickname at a recent press conference. “I think New Horizons is an example—one of the best examples in our time—of raw exploration,” he told reporters. “The term Ultima Thule, which is very old, many centuries old, possibly over a thousand years old, is a wonderful meme for exploration.”

The newly imaged object is certainly a frontier, one that’s frigid and mind-bogglingly far away. It’s the most distant place NASA has studied from relatively close up, and when the first batch of images from this New Horizons mission was released (the closest of which was taken from 17,000 miles away), many scientists and reporters reached for tropes that are instantly recognizable here on Earth.

Many have described its cinched, bottom-heavy shape as a snowman, while NASA suggested something like “a bowling pin, spinning end over end.” Marina Koren, at The Atlantic, likened the reddish, ruddy color to an iced coffee, swirled with half-and-half.

Something so remote and desolate stretches the limits of the imagination, but my Atlas Obscura colleagues have plenty of that. We spitballed some other suggestions for familiar things this alien body evokes. Consider, if you will:

- A peanut

- Cellular mitosis

- A cairn

- Someone blowing a bubble

- Nerds (the candy)

- A Death Star spawning a little baby Death Star

As higher-resolution images from the close-up flyby start to trickle in, we’ll get a clearer picture of the object’s features. That might make the distant world a little more intimate—but no less wondrous.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook