So Much Used to Depend on a Small Metal Cylinder in a Vault in France

The life and death of the physical prototype of the kilogram.

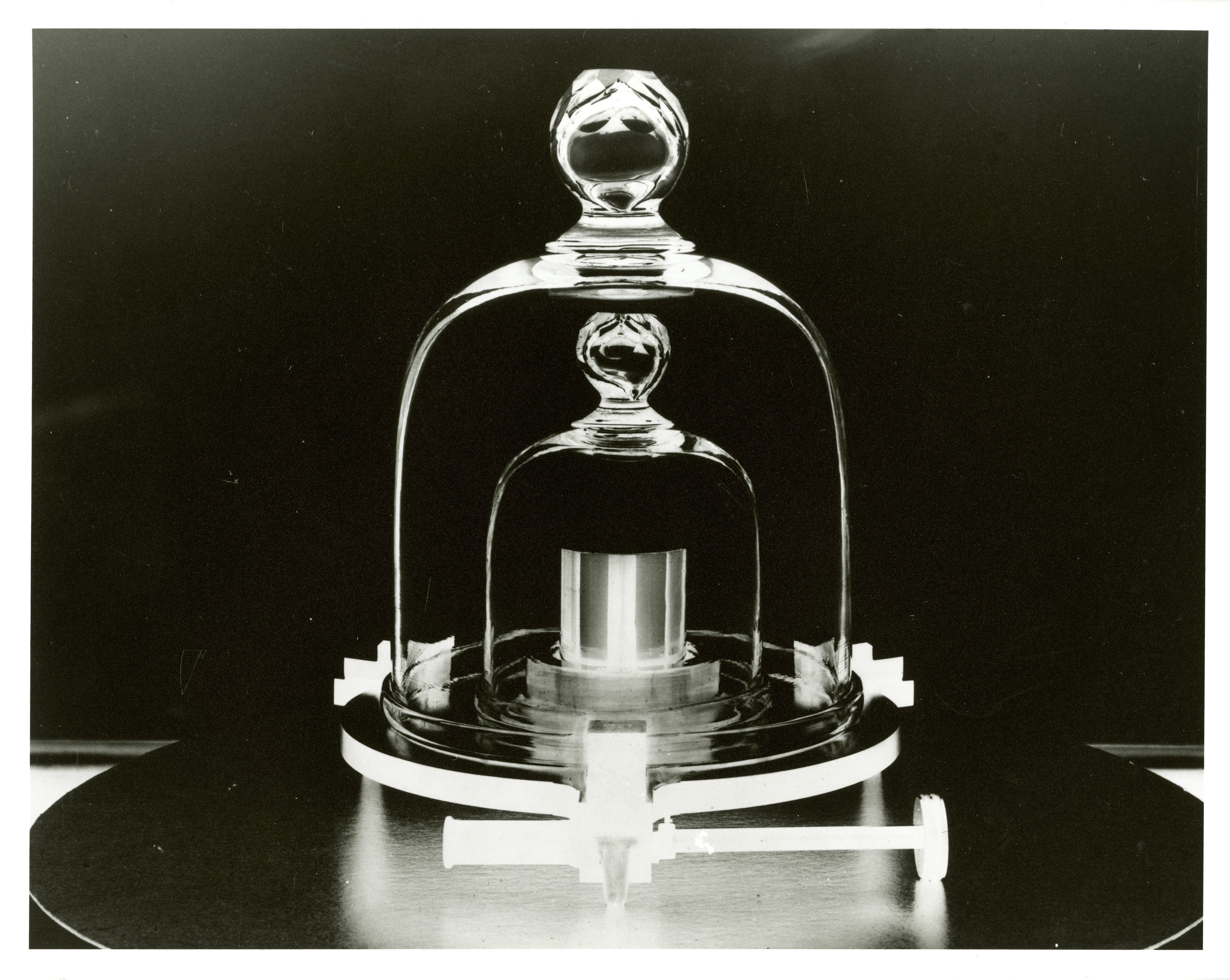

Nothing was supposed to change, not ever. The little cylinder, made of platinum and iridium, was supposed to stay the same, locked as it was inside a vault, and sealed within nested bell jars. That isolated life below the International Bureau of Weights and Measures, near Sèvres, France, was meant to keep the cylinder stable forever.

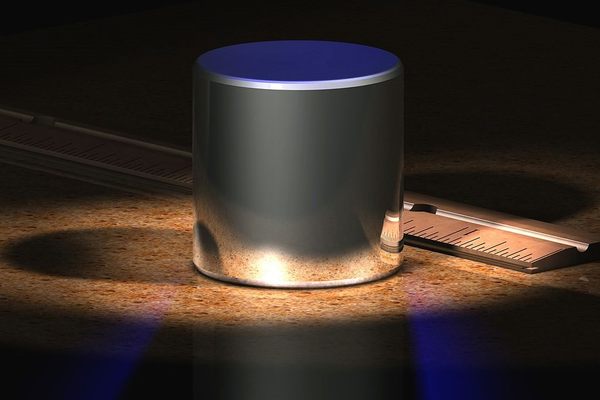

That steadiness was crucial, because the thing itself was crucial. Its mass was exactly, precisely one kilogram, not because that what it registered on a scale, but by fiat—it was the kilogram, and the kilogram was it. In 1889, the General Conference on Weights and Measures had anointed it as the supreme kilogram, the International Prototype of the Kilogram, the one against which all others were measured. And that was that, for a while. It slumbered in its vault, and was only trotted out once every few decades, to be compared to more than a dozen copies stashed around the world—for good measure.

The prototype and its cousins were all treated gingerly. Cleaning might involve nothing more than a gentle massage with a piece of chamois leather dampened with ethanol and ether. Two of the duplicates of Le Grand K, as the cylinder is known, are safe and sound under bell jars in a climate-controlled lab at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) in Maryland. “We don’t even try to touch them with gloved hands,” NIST scientist Zeina Kubarych recently explained to NPR. “You may rub some atoms off or something,” lead NIST scientist Stephan Schlamminger told National Geographic back in 2015.

Those concerns—not about cleaning exactly, but about the official kilogram changing—were well founded. Despite these precautions, the standard had become, well, not so standardized. Over the years, the prototype and its duplicates no longer match. The difference isn’t much—50 micrograms over a century, far less than the mass of a single grain of rice—but in the world of measurement and standardization, 50 micrograms is everything. It isn’t clear whether Le Grand K was somehow slimming down, or whether the other ones were putting on the atoms. Either way, the bureau decided that any degree of error was too much.

So, this week, the International Bureau of Weights and Measures voted to green light a new standard—one based more on physics than physicality. The cylinder will likely be supplanted by a sophisticated and sensitive machine, known as the Kibble Balance, which relies on Planck’s Constant and a magnetic field.

The change won’t come into effect for a few months. But when it does, the once-revered cylinder will join the ranks of other little objects that have outlived their use as standards of measurement. One ghost of meters past is an iron bar that also lived in France; U.S. President Benjamin Harrison accepted a copy in 1890.* An even earlier meter—this one standardized after the French Revolution and based on the distance from the North Pole to the Equator, through a Paris meridian—is mounted on a wall across from Palais du Luxembourg. A metal handle outside the city hall of Leiden, in the Netherlands, references the Rhenish foot, a unit of length that preceded the meter. Across the Channel, plaques against which Brits could stack up their measuring sticks are embedded into the ground at London’s Trafalgar Square and a wall at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich.

As for the cylinder, speculation has abounded about its fate for years. Writer Maya Wei-Haas mused about its future back in 2015, asking in National Geographic what would become of it when it was no longer mustered into service as a definitive measurement. “Anybody need a paperweight?” she quipped. In fact, Le Grand K will stay exactly where it is. “It is an historic artifact that has been under study for 140 years and will retain a bit of metrological interest,” noted its custodians, in a statement. Its cousins will remain cloistered in their bell jars, too.

But the shiny metal will have lost its symbolic luster. Relieved of duty, it will retire into a life as a smooth little cylinder—albeit one with a weighty history.

*Correction: This post originally referred to William Henry Harrison, instead of his grandson, Benjamin, and has been updated.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook