Why Elite Romans Decorated Their Floors With Garbage

This mosaic is trash.

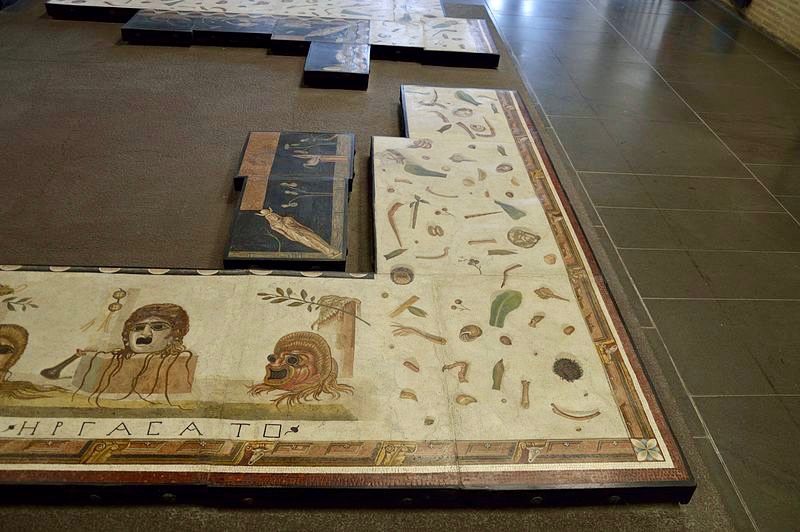

In the Vatican’s Profane Museum, there’s one artifact that looks out of place among the ornate sarcophagi and marble statues: a mosaic floor that seems to be covered in the picked-over refuse of a meal.

When you first look down at the mosaic, it looks like the kitchen trash tipped over: Nutshells, olive pits, fruit rinds, and grape stems are strewn about. But if you look closer, the food scraps dissolve into chunks of stone and chips of glass. It’s a trompe l’oeil in mosaic, and an extraordinarily fine one. The shells gleam, the chestnut husks bristle with spines, and the grapes are fuzzed over with a soft, velvety bloom.

Mosaics like this one formed the floors of triclinia, dining rooms in ancient Rome where party guests lounged on couches, picking at delicacies. This one was unearthed among the remains of a villa on Aventine Hill, and even now it emanates some of the atmosphere of one of those long, dim, boozy Roman banquets. The scraps of food cast long, erratic shadows in different directions, as if lit by the dancing flicker of oil lamps, and even the little mouse, nibbling on a nut in the corner, carries a white glimmer of reflected lamplight in its eye.

This motif is a surprisingly common one, enough so that it has its own name: asarotos oikos, or “unswept room” in Greek. Although Greek artists made the first “unswept room” mosaics, we have only later Roman copies, which were constructed during a craze for Greek culture. But why would an elite Roman go to such effort and expense to make their dining room floor look like it was covered in trash?

For one, it was a kind of sly status symbol. Consider the refuse represented in the collection of the Profane Museum (so named because it houses non-Christian art): It’s trash, yes, but trash of the most luxurious kind. There’s fresh seafood, rushed in from the coast, including lobster, oysters, and even the spiny shell of a Murex Brandaris, which was the source of the famous Tyrian purple that only the elite of Roman society were permitted to wear. Strewn among the shells are expensive imports, such as mulberries from Asia, ginger from India, and figs from the Middle East. The spoils of a whole empire are scattered on the floor.

The mosaic implies a feast so lavish that, if it were actually served, it might have been illegal—a violation of Roman sumptuary laws, which capped how much a host could spend on any one banquet. The Lex Orchia, passed in 182 BC, limited the number of guests that could be invited to a single meal, and later laws outlawed the consumption of fattened fowl, shellfish, and sow’s udders (a favorite Roman delicacy). But based on the accounts of feasts we have from this time, these rules were frequently flouted. After all, what better way to impress your guests than breaking the law to entertain them?

Art historians, however, have connected the motif to another Roman dining tradition: the memento mori, or “reminder of death.” These little references to mortality were all part of the fun at a Roman banquet. Little jointed bronze skeletons called larva convivalis, for instance, seem to have been used as party entertainment. One appears in the Satyricon, doing a jiggly puppet-dance on the table while the host declaims, “Alas for us poor mortals … So we shall all be, after the world below takes us away. Let us live then while it goes well with us.”

Viewed from this perspective, the mosaic was a demonstration that even the finest feast is quickly transformed from sustenance into trash, just as the diner will be reduced in time to bones and dust. In other words, enjoy your meal, because it might be your last.

Almost 2,000 years separate us from the diners who ate over this mosaic. The deaths they imagined came to pass; all that’s left is this image of their trash. But this trompe l’oeil mosaic still has a few tricks up its sleeve. In his book Courtesans and Fishcakes, James Davidson, professor of ancient history, points out this telling detail: Some of the food remnants don’t quite meet their own shadows, as if they are still a split second from hitting the ground. The diners may be long dead, but the feast rages on.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook