India’s Sati Stones Commemorate a Macabre Historical Practice

Their challenging legacy has complicated preservation and study.

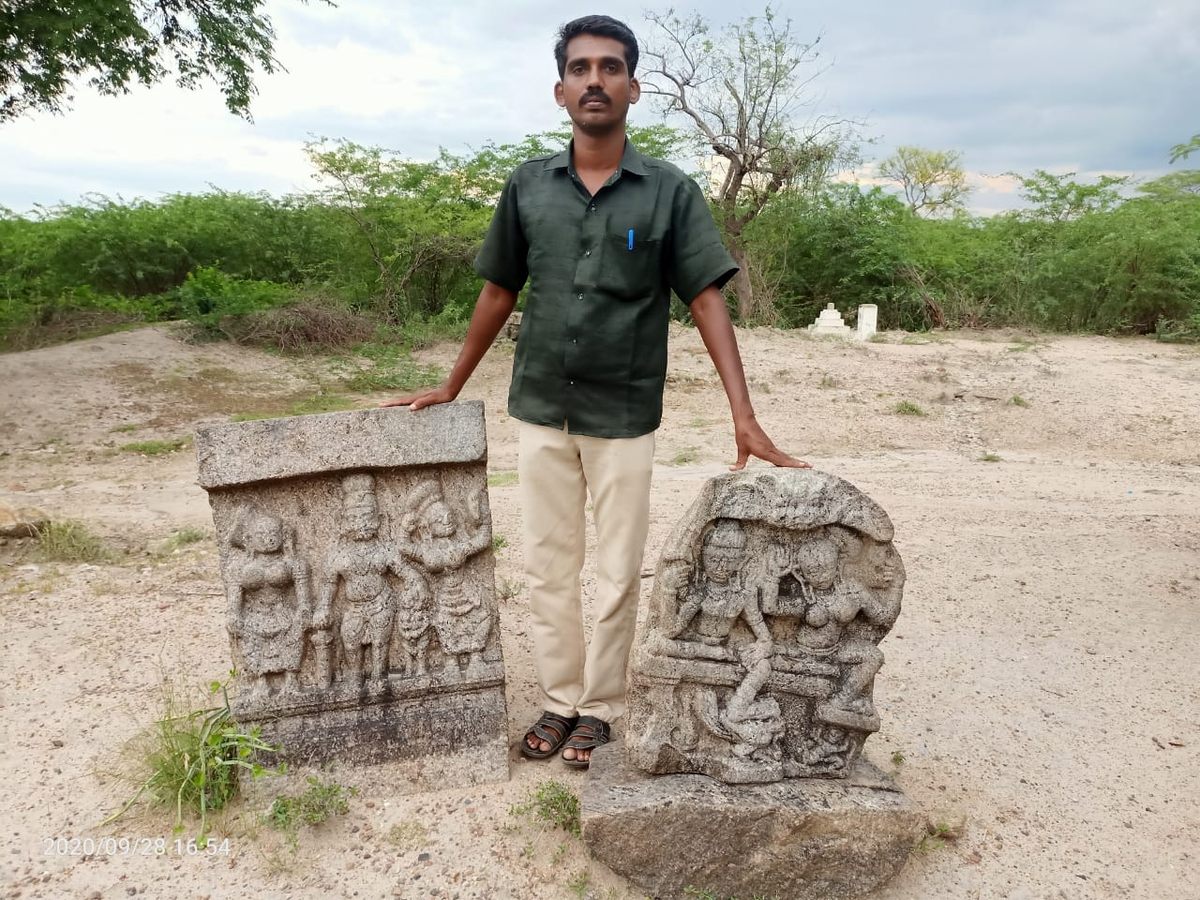

Every Saturday morning, around 8:30 a.m., Munaivar Muneeswaran, 37, head of the department of history at Saraswathy Narayanan College in Madurai in southern India, gathered his friends. They packed meals and essentials, and then set off on weekend-long archaeological expeditions.

These jaunts began in 2002, when he chanced upon an ancient signpost near his home in the village of Kavasakkotai. The sign mentioned a village called Velambur, but it didn’t appear on any map. Ever since, he says, he’s been obsessed with finding the spot where the mysterious village could have been. He decided to comb a radius of 12 miles around his home, reasoning that the village wasn’t likely to be far from the signpost. For many years, Muneeswaran and his friends came up empty.

In mid-July 2020, in a village called Chatrapatti, not far from his home, he stumbled on the remains of a defunct post office that carried the name Velambur on a dusty sign. Inside, he found old rubber stamps with the name, too. So he began to search for a statue, an edifice, anything that could possibly confirm that this was the village he had sought for nearly two decades. But in a seemingly abandoned part of the agricultural area, he made a completely unrelated discovery.

“People were worshipping in the vicinity, but we couldn’t see an idol or temple,” he says. “Why were they praying here? What significance did the spot have?” Thinking that it could be the key to finding the old village, he recruited locals to search through an area covered in brambles. They hacked away at the wild overgrowth, and in an hour they had uncovered three stones, estimated to be at least 400 years old. Roughly 3.5 by 2.5 feet each, with one slightly smaller than the others. Muneeswaran knew that he had found sati stones, memorials erected to honor the widows of men killed in battle—widows who, by way of both grief and tradition, had immolated themselves on their husbands’ funeral pyres.

These weren’t the first sati stones that Muneeswaran had encountered. In 2017, in a village called Kasipuram, three miles from his home, beside an old tank overrun by thorns, he found what appeared to be 10 of them, seven of which were still clearly identifiable after centuries of exposure. When he researched the history of the area, he found that it was once part of another lost village, called Madhamamnayaknur, in an area where elephants had been trained for combat in the 16th century.

The three stones that he uncovered at Chatrapatti, however, were different. Instead of a sculpted handprint that represents the women who died, a usual feature on most sati stones, these had been intricately carved. Two of the stones had three figures on them—a man flanked by two women—though one was severely weathered. It suggested that these may have a royal lineage.

“The ornaments on the central male figure were indicative that he was of royal birth, quite possibly King Kausilan who ruled these parts in the 16th century,” he says. “The king was flanked by two of his wives. The figure of the queens are adorned in jewelry, indicating that they died as sumangalis, or married women on his funeral pyre.” The women each carried a lemon in one hand and a mirror in the other, common symbols on sati stones, as women might have carried such items to their deaths.

Sati stones have been found across India, says S. Sumathy, head of the department of anthropology at the University of Madras. And they turn up all over, in unexpected places.

“The practice was far more prominent in northern and central India, believed to be widely practiced among the Hindu community, particularly the Rajputs, a warrior clan,” she says. “In the states of Rajasthan, and in Maharashtra, Gujarat, and Goa. In south India, it was prevalent in Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu.”

The practice of sati appears to have been prominent in the early years of the Mughal rule in India—which lasted from 1526 to 1857—when the religiously diverse subcontinent was mostly governed by an Islamic dynasty. As a result, sati stones have a rather contentious history, still fraught with religious and political tension.

“If we paid attention, there are many tales from our past that these stones could tell—for instance, that this was a society that prized virginity and demonized widowhood, that it was beset by frequent wars and unrest, which drove women to take their own lives rather than end up as prisoners of war or victims of rape by a pillaging enemy,” Sumathy says. Over time, the practice was glorified. The women were praised and worshipped for their bravery and chastity. But the issue of whether they consented to the practice is complicated, she adds. “Even if the women chose to willingly die with their husbands, this isn’t considered real consent. Sati was so much a part of a rigid religious and moral code that prevailed in society at that period in history, and women, especially the elite, were expected to conform, to set an example, or risk being ostracized.”

Even today, controversy over sati stones erupts on social media and finds its way into the news. In an India ruled by Hindu nationalists and heavily polarized along religious lines, Muslims have recently been portrayed, in a historical context, as invaders and conquerors, to the extent that cities bearing the names of Mughal kings are currently being re-christened. Sati stones, and the fear of invaders they represent, inadvertently fit into that narrative.

“The first clear evidence of sati existed in Eran in Madhya Pradesh in 510 AD,” says Ameeta Singh, a professor of history at the Government Maharani Lakshmi Bai College in Bhopal.

Eran—referred to as Erakaina or Erakanya in Buddhist and Hindu texts—was an ancient city where evidence of the practice was found inscribed on a pillar. (Mentions of the practice go back even further, to the Greek historian Aristobulus of Cassandreia, who wrote of it while traveling with Alexander the Great.) Singh has been documenting sati stones in central India since 2015, ever since she learned that one of her ancestors, a woman named Rupai, had committed sati herself. Her family hails from Falodi in Rajasthan. When Singh visited her ancestral village, she found seven sati memorials, including one for Rupai. Since then, she’s combed the length of Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh, decoding the inscriptions on thousands of examples.

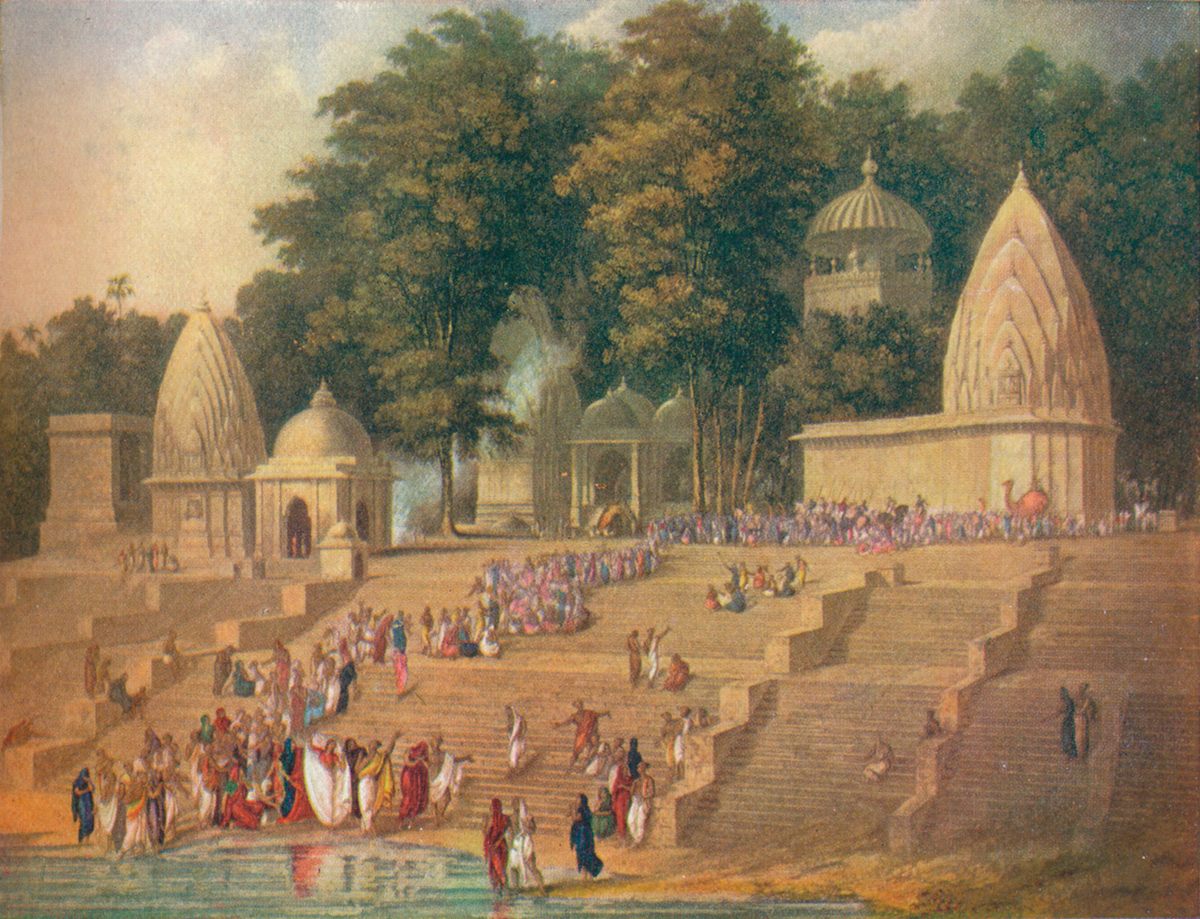

She read many, often disturbing, historical eyewitness accounts, including that of 17th-century Italian traveler Pietro Della Valle. He wrote of a sati procession in the town of Ikkeri in the south Indian state of Karnataka. The widow mounted on a horse, a lemon in her right hand and a mirror in her left, while a band played. “The people in the procession sang her glories and admired her sacrifice,” he wrote.

Fanny Parks, a Welsh writer known for her extensive journals of colonial India, sketched many sati memorials that she’d visited during her two decades in the country. “Like Parks, I’m fascinated with its historical value and sketch the memorials, writing my account as a woman and a wanderer,” says Singh.

Over the years, Singh has tabulated and mapped sati stones across central India. The stones are often found in clusters, she says, with a higher density in key cities such as Vidisha, Gwalior, Shivpuri, Rajgarh, Sagar, and Orchha. There are fewer sati stones in rural or tribal areas, indicating that the practice was more prominent among the warrior clan. They are also more prevalent near the sites of ancient battlefields, such as Khimlasa, Bangla, Sironj, and Amjhera in the state of Madhya Pradesh. The largest concentrations was found in Udaipur and Jaisalmer in Rajasthan, at royal cremation grounds.

“The inscriptions on the stones written in the Devanagari script [an ancient Indian script] suggests that the custom was widely prevalent from the 10th to 18th centuries, but the maximum number of deaths from sati occurred from the 14th to 17th centuries,” Singh says. “There is still much we don’t know about sati—its ideology, ethnography, culture. All we have are the traces left behind in eyewitness accounts, and in the stones.”

The inscriptions might include personal information, such as the names of members of the woman’s family, and her husband’s name and profession. Singh observed in her work that the pillars in north and central India have distinctive features such as cenotaphs, riders, and warriors, and in that way bear similarities to Greek and Roman motifs.

Some feature sculpted images of couples and symbols depicting worship of the Hindu god Shiva. Carved into the stones are also suns, moons, mirrors, and waterpots, motifs that span the range of the practice. Researchers assume they represent purity and reference items a woman might have carried to her death.

But not all stones carry such detail. In the north Indian state of Maharashtra, very few sati stones have inscriptions, says Pune-based archaeologist Manjiri Bhalerao, a specialist in Indian studies at Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth University. Such less-ornate stones are often subject to vandalism, or could be reused in the foundations of homes, she says. “We need to view these stones objectively, preserve them better, and study them as neutral artifacts that are part of our heritage.”

That heritage lingered well into modern history. The practice so horrified the British colonialists that on December 4, 1829, Governor-General William Bentinck passed the Bengal Sati Regulation, a law that made the practice illegal. However, sati stones continued to be worshipped, and it wasn’t until 1987, when an 18-year-old widow named Roopkuvarba Kanwar, who had been married for a mere eight months, was forcibly burnt on her husband’s funeral pyre in the village of Deorala in Rajasthan, that the Indian government stepped in to strengthen laws and enforcement.

Any ceremony associated with the stones and attempts to commemorate or honor the women became prohibited. While these laws were welcomed, they complicated archaeological preservation of the stones themselves. Researchers drew criticism for studying them and many of the sites—such as those Muneeswaran encountered—sank into neglect.

“These sites are in urgent need for protection and preservation,” he says. He is now petitioning a local museum to help get the area in Chatrapatti village declared a protected site. “The stones are more than memorials. They contain a wealth of insight into pockets of our local history that we can’t afford to lose.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook