What in the World Was a Key-Footed Glyptodon?

It had a shell as big as a car.

Back in 1834, in southern Patagonia, Charles Darwin found a set of fossils that he just couldn’t explain. He thought that the bones might have belonged to a mastodon. Richard Owen, a contemporary of Darwin’s and an anatomist, had a different idea. In his view, the creature, now extinct, was about the size of a horse… or a camel… or a llama? He suggested the name Macrauchenia, the “long llama.”

The story of Macrauchenia only became more complicated as more fossils were found. Its skull indicated that it had a proboscis of unknown size, like a tapir’s or maybe an elephant’s. This creature had lived in South America, which was isolated enough to make fitting native fauna into the larger family tree of life difficult at time. It wasn’t until 2017 that DNA tests revealed that Macrauchenia’s ancestors had been related to the branch with rhinos, tapirs, and horses.

These are the mysteries of megafauna, animals that lived not so long ago in geologic time, but far enough in the past that we don’t know too much about them today. In a new book, End of the Megafauna, the paleomammalogist Ross D.E. MacPhee, who works at the American Museum of Natural History, explains the going theories about what these creatures were like and how they disappeared. Many scientists believe hunting pressure from migrating humans and other hominins may have done these creatures in; others believe ecological and climate change wiped them out. (Less popular theories include food web problems, disease, and a giant fireball.)

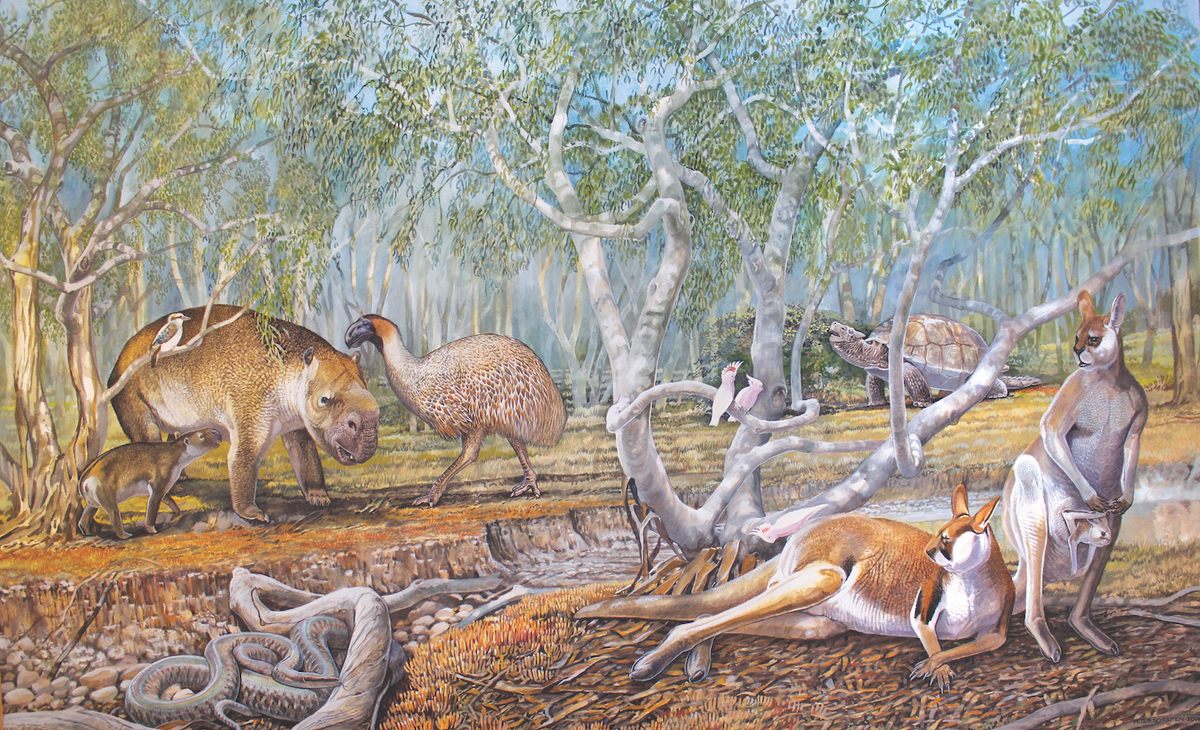

These animals have an uncanny familiarity—they resemble animals that we know from our own time, but also they’re different. The bibymalagasy, for instance, may have been something like an aardvark, although it’s hard to know. The mihirung was a giant bird related to ducks and sand geese. The giant diprotodont, though, was a large marsupial that might have looked sort of like a rhino with no horn. And what in the world was a glyptodon?

The End of Megafauna features more than one glyptodon, illustrated by Peter Schouten. There’s a morning-star tailed glyptodon and a key-foot glyptodon. These guys were “the last of the giant armadillos,” MacPhee writes—they weighed anywhere from 4,400 to 5,275 pounds. (Today’s armadillos, he notes, weigh in at 55 pounds.) They’re known in part from the armored carapaces found in the fossil records—shells so big that they could be cars. Their tails, paleobiologists think, were used to fight each other: Some of the carapaces have serious dents in them.

Some scientists think that if human hunting drove all these guys to extinction, we’d have found more bodies, MacPhee explains—more sites showing evidence of that hunting on a dramatic scale. As it is, the evidence of this not-so-distant past allows us to imagine a world filled with unfamiliar creatures, still clearly connected to our own. In the top illustration, the two birds perched on the glyptodon are species that are extant. The biology of Earth can change quickly, with some survivors and some creatures—even giants—never seen again.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook