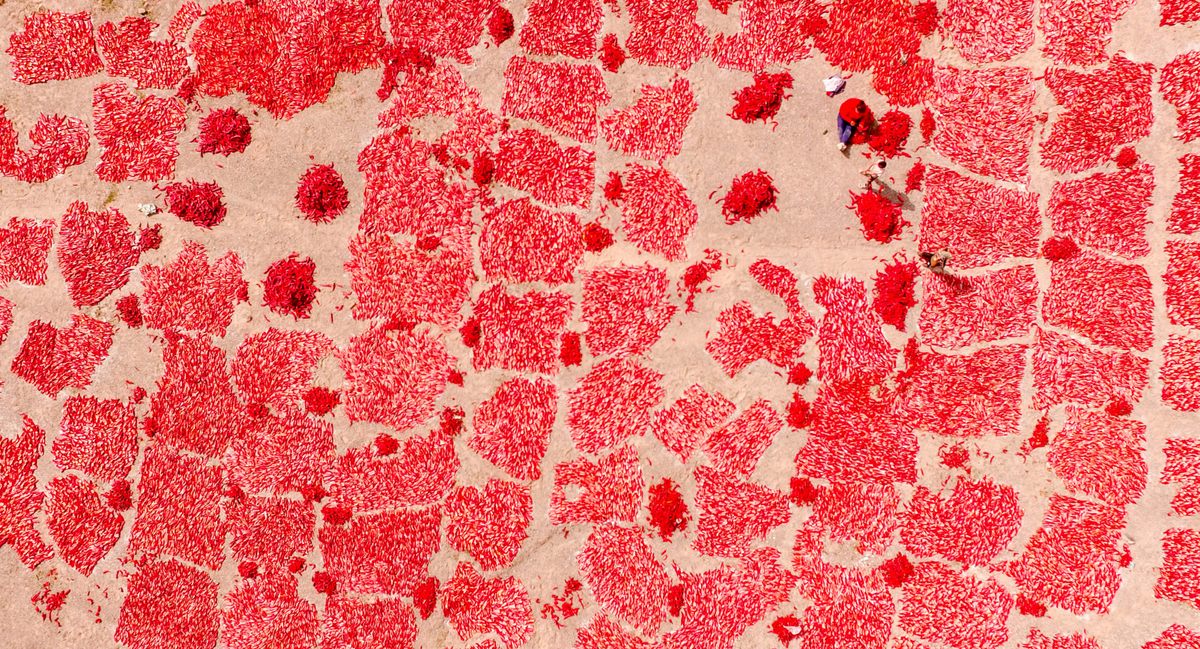

The Gobi Desert Is a Red Sea of Chili Peppers

They dry in the sun every autumn in China’s Uyghur Autonomous Region.

In Northwest China’s Gobi Desert, autumn tints the landscape a flaming scarlet. The fields of red aren’t deciduous leaves blushing with the season. They’re chili peppers, spread out to dry under the hot desert sun following the late-summer harvest. Each September and October, farmers across the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, which produces a fifth of China’s world-leading pepper harvest, let the harsh sun and 100-plus degree temperatures do the work that most American producers leave to industrial dehydrators.

The result is a red sea of chilies stretching to the horizon. From the ground, the mounds of glossy, fat peppers look like tempting seasoning for a future dinner. From above, the two hundred-plus ton harvest transforms the landscape, staining the khaki-colored desert like blood cells under a microscope.

Blanketing the arid sand of the Uyghur Autonomous Region, the chilies are part of a spice economy that stretches back to the heyday of the Silk Road. Until the 16th century, native spices such as cumin dominated Central Asia’s spice trade, and they continue to flavor the cuisine of the Turkic-speaking, majority-Muslim Uyghur people who call this region home. Chilies reached China sometime in the 1500s, one of the many New World foods to spread in Asia as a result of European conquest in the Americas. Chilies took root both in the dry desert soil and the local cuisine.

While the food of southwest China’s Sichuan Province is popularly associated with hot peppers, Xinjiang’s Uyghur food doesn’t neglect the spice. Fitting the region’s status as a cultural crossroad, Uyghur food contains culinary traces of South, Central, and East Asia. Manta, which are beef-and-pumpkin stuffed dumplings, evoke Turkish or Afghani mantu. Goshnan (“meat bread”), a stuffed flatbread, has consonance with South Asian keema parantha. Lagman, a bell-pepper-and-onion studded dish sometimes made of one impressively long noodle, resembles Chinese lamian. While many of these dishes are oily and aromatic rather than spicy-hot, kawaplar, chili powder-dusted lamb kebabs, and dapanji, often translated as “big plate” chicken stew, make mouth-numbing use of the region’s chili harvest.

Particularly in light of the Chinese government’s ongoing persecution of Uyghur people, which has forced community members into “re-education” camps and prohibited them from practicing their faith, many Uyghurs are proud of what makes their culture and cuisine distinct. “Uyghur is Uyghur and Chinese is Chinese,” Ilshat Hassan Kokbore, president of the Uyghur American Association, said in an interview with the Washington Post. “Culturally, food is part of the Uyghur identity.”

The chili harvest is just one of the annual rituals that make the Uyghur’s homeland unique. Locals take advantage of the same hot weather that desiccates chilies to sweat in “sand baths,” burying themselves in burning sand as part of a traditional therapy. Like the health-seekers sweating for longer life, chili peppers in nearby fields dry as a means of preservation. The image of their glossy skin vibrates in the heat-iridescent air, while their smoky scent drifts through a desert region that continues to be one of the world’s crossroads of spice.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook