The Cheese Makers Keeping Monterey Jack’s Local Legend Alive

Only one farmstead in Monterey County still makes the famed cheese.

This article is adapted from American Food: A Not-So-Serious History by Rachel Wharton, illustrations by Kimberly Hall.

Depending on your point of view or your politics, you might subscribe to one of four theories as to who invented Monterey Jack cheese, all of which are detailed in essays preserved on the website of the Monterey County Historical Society in Central California.

One: It was Roman monks who taught cheese making to the Majorcan missionaries who founded the missions on what is now the central coast of California in the 1770s. (And who bulldozed over the native Rumsien and Esselen people to create a new Californio culture.)

Two: It was Doña Juana Cota de Boronda, a Spanish-Mexican-German woman. Her family received the 6,625-acre Rancho Los Laureles in the Carmel Valley as part of the Mexican land grants from Spain, before California became a state. Her great-granddaughter wrote to the Monterey Historical Society about her father’s memories of using a handmade jack to press the curds into cheese, then just called queso del país, or country cheese. Doña Boronda, stories go, had to sell this cheese door-to-door to feed her 15 children after her husband was injured.

Three: It was a Swiss-Italian California dairy man named Domingo Pedrazzi, who also made a jack-pressed cheese in the late 1800s, which he sold under the name Del Monte Cheese.

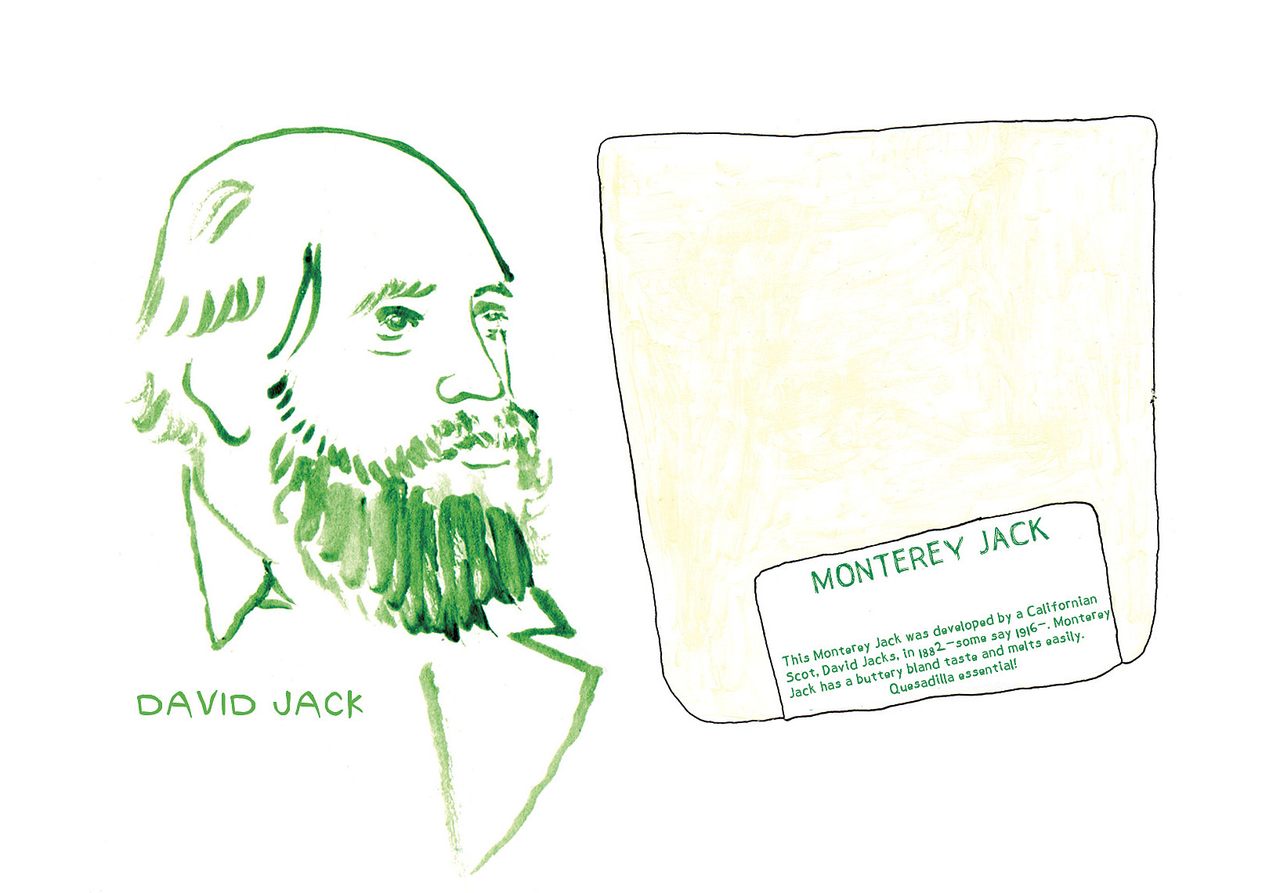

But the most fun to tell by far is the tale of David Jacks, born David Jack in Scotland, who moved to California during the Gold Rush of the 1850s. The synchronously named Jack (the man, not the press) didn’t find precious metal, but he did eventually legally bamboozle the government out of 30,000 acres of land, an acquisition that eventually enabled him to buy up most of the peninsula from Pebble Beach to Monterey’s historic Mexican missions. That included many dairies making country cheese, including Dona Boronda’s well-regarded queso del país, which he started marketing and exporting around the country possibly on her behalf, probably with his name and “Monterey” on the boxes, so it eventually became known as Monterey Jack.

“They’re all probably true; it’s not voilà—it’s Monterey Jack,” says Beau Schoch of Schoch Family Farmstead in Salinas, a third-generation California dairy farmer whose family is currently the only one making Monterey Jack in Monterey County. Like most who know the cheese’s history, he believes it started out as a process—the time and temperature at which the milk ferments, the way you cut the curd to make a smoothly textured cheese, the jack that presses out the liquid—and that likely many people were making it.

“At some point, somebody said, ‘Oh, what’s this cheese? It’s jacks cheese in Monterey,’” says Schoch, whose grandfather was a German-speaking Swiss dairyman who came to the United States in the 1920s to escape the flu then ravaging Europe.

No matter your take on the past, Schoch is the standard-bearer of the future. It is an American travesty that most of us think of Jack cheese as the rubbery white squares sold in every supermarket. At its best—which is to say, as made by artisans such as Schoch—it is a rich, buttery beauty that deserves its due as one of this country’s first artisan cheeses, best eaten out of hand instead of melted on beans and burritos.

Several makers around the country do produce similar special versions, but Schoch is the only one to do so in its original terroir. This is hilly land just off Highway 101, land that has been grazing cattle since mission times, once a rancho owned by a Mexican land grant family by the name of Espinosa. (Their original adobe house was torn down by Schoch’s grandfather, says Schoch, but one of Doña Boronda’s still exists, if you want to see it.)

Cheese making is brand-new for Schoch’s family, who produce both regular and aged Monterey Jack, plus many other artisan rounds of Schoch’s own creation. For him it’s part of a broader plan to stay in business, now that they often earn less than it costs to produce their milk if they sell it to national distributors. (He originally thought about growing grapes and making wine, until he realized his family already grew cows.) The Schochs also make Swiss-style stirred raw-milk yogurt and bottle some of their own milk to be sold at local grocery stores and food shops along with their cheeses.

Decades ago, there were 300 to 400 dairies in this area. Now there are just two or three. Schoch remembers when his family used to graze twice as many cows in the fields across the highway, before the area’s huge fruit producers realized you could grow strawberries on those hills, too.

Schoch’s family land is some of the most valuable agricultural land in the country because of the cooling fogs, constant sun, and fertile soils. In fact, this land is known as the “salad bowl,” home to much of the lettuce sold nationwide, as well as artichokes, strawberries, and cherries. In some ways, that’s good for milk, yogurt, and cheeses. Schoch’s cows, a mix of Holstein, brown Swiss, Swedish red, and Montpelier, get leftover unsold fresh lettuce when they’re not eating his green grass. (“It’s better greens than you’re getting in New York City,” Schoch tells me.)

Today, their own labeled products are made from just 20 percent of the milk they produce, Schoch says, but he hopes to slowly grow the side business. Who knows? Maybe other Monterey County–area dairy producers will join him, making the region’s past their future.

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook