Thomas Edison Was an Early Adopter of the Word ‘Bug’

In an 1878 letter, he uses the term to refer to a technological glitch.

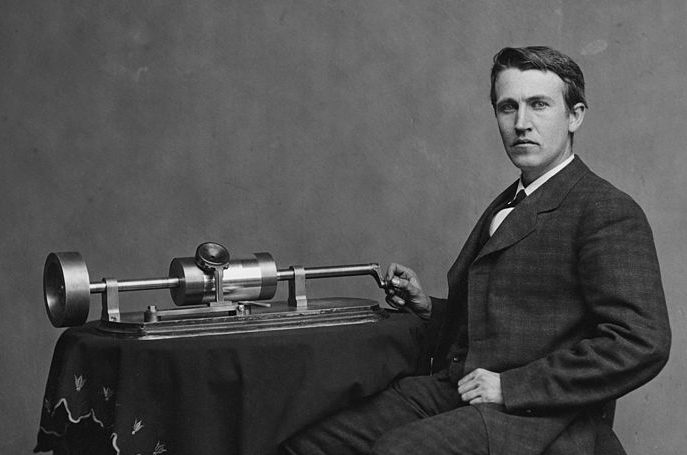

In 1878, Thomas Edison’s star was on the rise. A few years before, when he sold his quadruplex telegraph design—an industry-changing innovation that allowed four signals to go over one wire—he had used the proceeds to build his lab in Menlo Park, New Jersey. Soon enough, he would start work on his lightbulb and the motion-picture camera, the work that would make him one of America’s most lauded scientists. But already newspapers had started hailing him as a genius, after he debuted the phonograph in 1877.

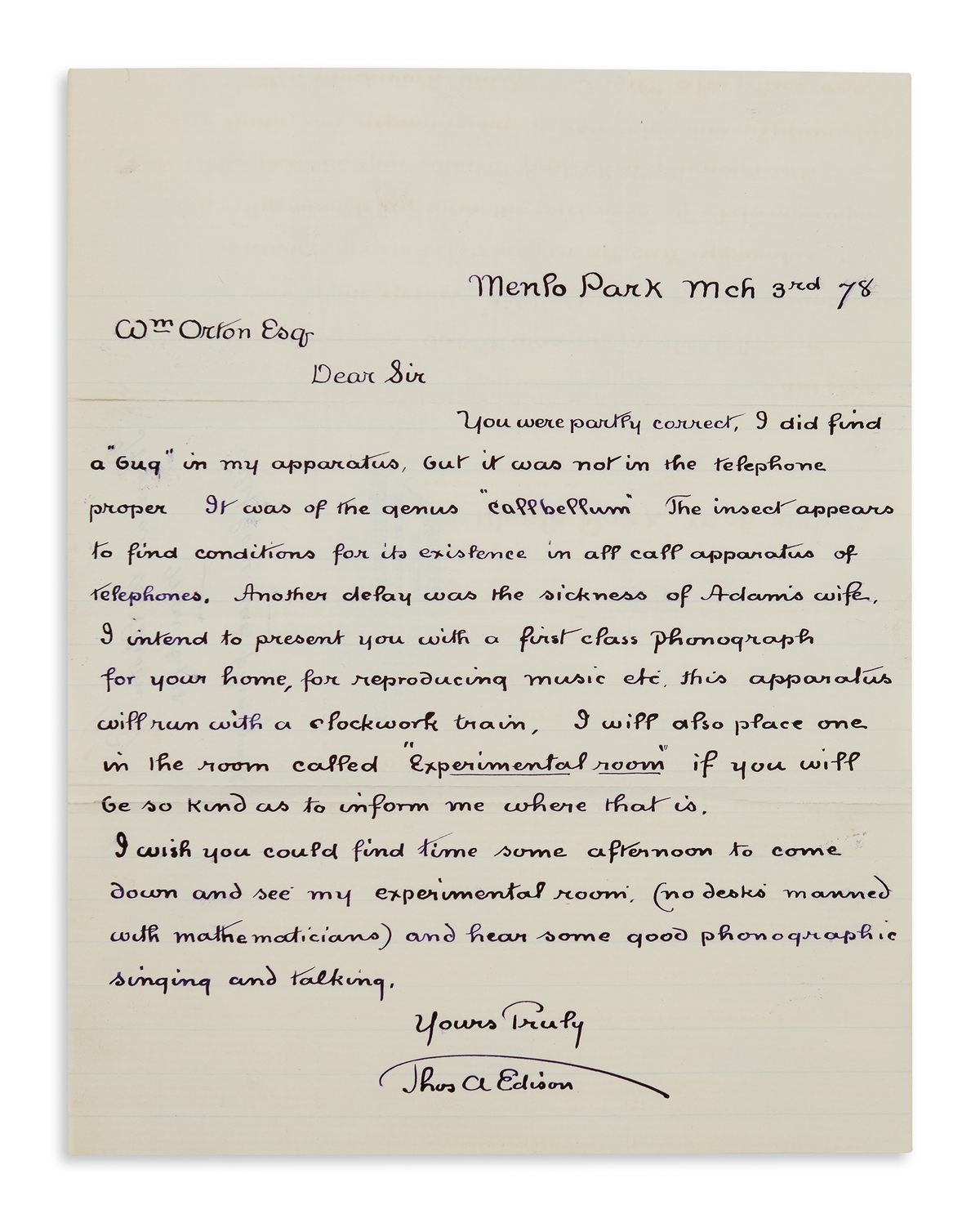

Now, though, Edison was focused on improving the telephone—a job he took on for Western Union, which was eager to rival Alexander Graham Bell’s new communications company. In March, Edison wrote to William Orton, Western Union’s president, updating him on a conversation they’d had in person about a new telephone design:

“You were partly correct, I did find a ‘bug’ in my apparatus, but it was not in the telephone proper. It was of the genus ‘callbellum.’ The insect appears to find conditions for its existence in all call apparatus of telephones.”

This letter, at auction next week at Swann Galleries, is one of the earliest examples of this use of “bug,” to describe a problem with technology.

That coinage is sometimes attributed to U.S. Navy Rear Admiral Grace Hopper, who in 1947 found an actual bug (a moth) in a Mark II computer. She taped the moth in a log book and wrote beside it, “First actual case of a bug being found.”

But by the 1940s this type of bug was already well-known. Edison started using the term in the 1870s, while working on the quadruplex telegraph, which needed a “bug trap” to work properly. By 1878, it had become part of his lexicon: He used it often in his notebooks and had started spreading the term outside his own lab, to people like Orton.

Orton kept the 1878 letter; it came to Swann Galleries as part of a larger estate that included, as well, the draft of a contract between Edison and Western Union. The “callbellum” bug that Edison was referring to was likely in the wires that connected the receiver and transmitter, says Marco Tomaschett, a Swann Galleries specialist.

At this point in his career, Edison was invested in maintaining a strong relationship with Western Union, a major source of income for him.

“He didn’t write this way always, but he was trying to give a good impression—he’s about to renegotiate his contact,” says Tomaschett. “He wants to make a good impression. But he’s famous, so it’s not as if he’s groveling. He’s got quite a bit of clout.”

Eventually, Edison worked out the bug in the telephone. Western Union used his work, along with designs from other inventors, to try to challenge Bell Telephone’s hold on this new technology. The two communications companies fought over the telephone for years in court, until Bell Telephone walked away triumphant. By then, Edison was onto a new battle—the so-called “War of Currents” that determined how electricity would flow over wires into households across America.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook