America’s Early Female College Students Held Illicit Fudge Parties

“Vassar chocolates” became emblems of women’s education.

In the late-19th century, students tip-toeing around Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York, under the cover of darkness usually had a single purpose: illicit snacking. Students at the then all-female school made a game of sneaking food into their rooms, frying oysters on hatpins over gas-jets, and hiding everything from “lynx-eyed” teachers in the dormitory corridors. The chance to eat rich food sent from home and stay up past their strict 10 p.m. curfew was a thrilling adventure for young Victorian ladies. But chief among all their treats was simple fudge.

Legend has it that Emelyn Battersby Hartridge, Vassar College class of 1892, invented fudge. But its origins are more mysterious. Various fudge-like treats have long existed by other names, and in a letter written after her college days, Hartridge claimed to have gotten the recipe from the cousin of a friend in Baltimore. But what is indisputable is that Hartridge introduced it to Vassar College in 1888, and American female college students would soon churn out fudge by the ton, popularizing the treat and indelibly associating it with women’s education.

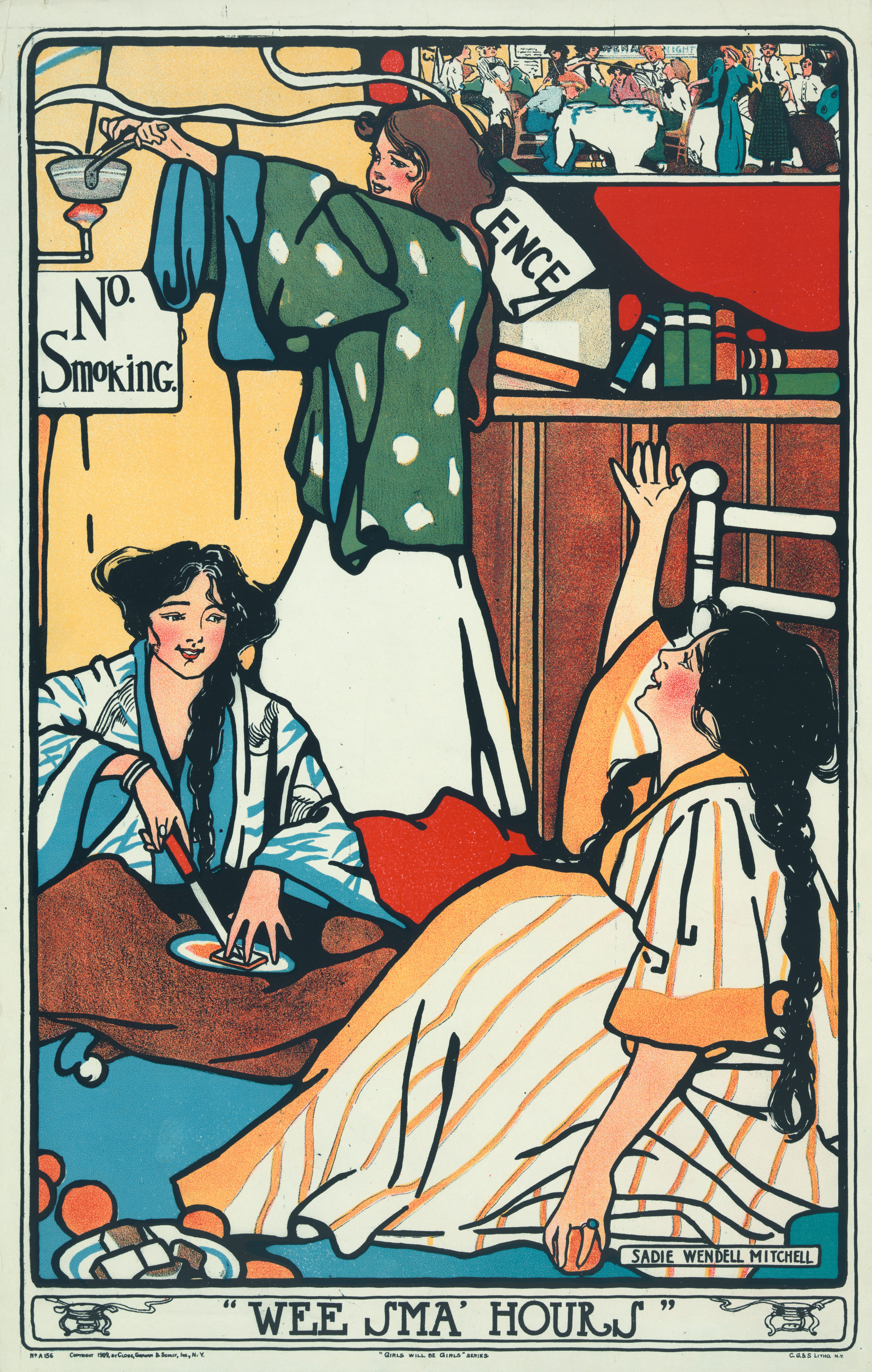

For this reason, early fudge recipes introduced it as “a college dish.” In 1897, the New York Tribune noted that it was best enjoyed “when a dozen or more girls are congregated in a room, sitting on sofa cushions spread out on the floor in a mystic circle around an alcohol stove, from which the odor of ‘fudge’ rises like incense.” Even for the modern college student cramming a contraband toaster into their closet ahead of an RA inspection, the idea of making fudge on an alcohol burner in a dorm room might seem perilous. But the young students didn’t care. In fact, an alcohol burner was on the staid side of things. Students often cooked over their wall- and ceiling-mounted gas lamps, and held pans full of molten fudge in the air to cool it. One early mention of fudge, in fact, comes from a 1893 poem in the Vassarion:

What perches us upon a chair

To stir a sauce-pan held in air,

Which, tipping, pours upon our hair —

Fudges.

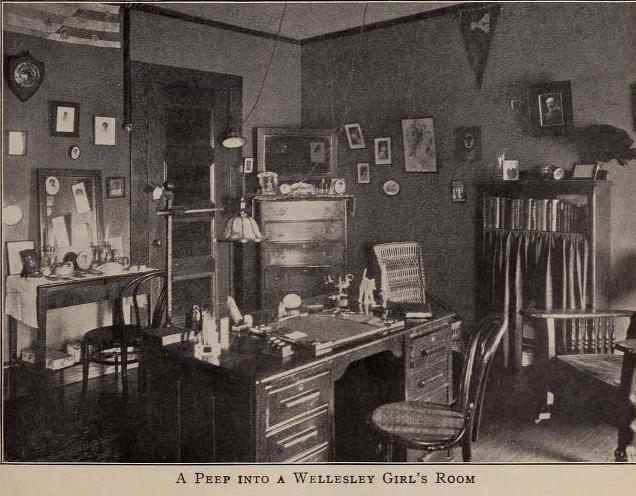

From Vassar College, fudge spread, becoming a college fad. (For a while, fudge was even known as “Vassar chocolates.”) Vassar students made a classic fudge of chocolate, butter, and sugar; the Wellesley College version was filled with marshmallows, and Smith College students used molasses.

But for all these undergraduates, making fudge was not just an indulgence—it was a form of mild rebellion in an environment that, even as it promised empowerment, still sought to strictly control them.

In the late-19th century, women students led more restricted lives than their male counterparts. (As one article from 1901 noted, “There is no case on record where students from a girls’ college have spent the night in the town lockup, as the result of reckless misbehavior.”) Students would gather secretively to eat fudge, oysters, and Welsh rarebit after their 10 p.m. curfew, and even this provoked a reaction. Compared with other sweets, such as seductive bonbons, fudge was considered morally benign. But health-wise, it was quite another matter. Turn-of-the century health professionals urged bland diets that used meat and spices sparsely.

S.T. Rorer, a prominent food writer known as America’s first dietician, toured the Seven Sisters in 1905 and noted disapprovingly that “the scholastic standing of the students was held in far greater importance than the more practical side of their education” (that is, learning how to be a wife and mother). Not only that, she railed against “the great desire of girls for sweets,” particularly fudge. If a female student wasn’t fed correctly, she mused darkly, they would turn to fudge instead. “In a little while she is in the infirmary, suffering a bilious attack,” she wrote, since “dinners of fudge have overworked her liver.” Improper eating with the addition of fudge, she wrote, had the capacity to “kill the weak and ruin the middling.” On the other end of the spectrum, writes women’s studies researcher Sherrie A. Inness, administrators “worried that ‘fudge-fuddled’ minds might hinder the academic progress of their students.”

The food at the original home of fudge, Vassar, rated particularly low in Rorer’s estimation. Yet her opinion didn’t seem to have much of an effect. Vassar women mocked anti-fudge opinions, as in a Vassar publication that depicted a fictional alumna scolding a current student for enjoying fudge. (“Can it be that the Vassar girl has fallen so low? In my day we ate our good wholesome mutton-stew without a thought of such proceedings, destructive alike to physical and moral welfare.”) According to Innes, “Welsh rarebit and pans of chocolate-nut fudge or sticky molasses candy at midnight were indicative of a student community that was increasingly unwilling to accept the strict control and regulation that earlier women’s college students had tolerated.”

Some students defended themselves by pointing out that their food shenanigans were mild compared to those of their male counterparts. “We did not at college, like some of the young men, drink whiskey, or steal gates, or shoot pistols at policemen, or club baseball umpires,” wrote one former Vassar student in 1891. And midnight feasts of candy and oysters, after all, are pretty tame. “Certainly not all spreads took place under the cover of darkness,” writes Lynn Peril in College Girls: Bluestockings, Sex Kittens, and Co-eds, Then and Now. “But breaking dormitory lights-out rules by meeting at midnight added an extra fillip of excitement and provided a way for well-bred college women to flout authority.”

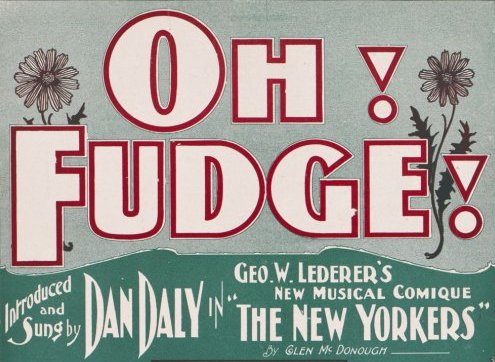

Eventually, the fudge-student connection became something of a cliche. One fed-up student in 1906 complained that popular novels had tied female scholarship too closely to fudge. “I once asked a man what he thought of particularly in connection with a girl’s college,” she wrote indignantly. The answer, of course, was fudge. Yet over time, fudge spread to beachfronts and boardwalks, while, Peril writes, dorm-room spreads became so staid that advice books informed young women at school how to ask permission to hold them. Peril, to say the least, is not impressed. “Had those turn-of-the-century larking College Girls asked for permission before breaking out the chafing dish and fudge pan? Not on your life!”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook