1916’s Song Of The Summer Was the Fake-Hawaiian Tune ‘Yaka Hula Hickey Doola’

One hundred years ago, Tin Pan Alley met Hawaii, and it didn’t go great.

One of 1916’s hottest songs. (Image: Library of Congress/55/3700)

Each July, as the sun beats down and hot-weather revelers turn up, a battle wages on the streets of America: what will be the Song of the Summer? This year is no exception: is it Drake’s lackadaisically pleading “Once Dance?” Beyonce’s stompy, unapologetic “Sorry”? Could it be “Panda”? The debate rages on.

A century ago, there was no use even arguing. The Song of the Summer of 1916 was called “Yaka Hula Hickey Doola,” and it went like this:

“Down Hawaii way, where I chanced to stray / On an evening I heard a Hula maiden play,” crooned vaudeville duo Van and Schenck. “Yaaka hula hickey dula, Yaaka hula hickey du.”

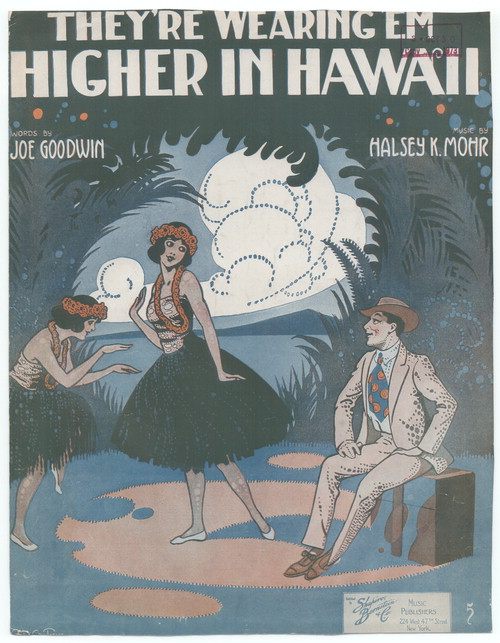

In case it is unclear, “Yaaka hula hickey dula” is not an actual Hawaiian phrase. (It’s also difficult to “chance to stray” to a set of islands in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, but there you go.) The runner-up summer songs of 1916 are equally dubious. “There’s another one called “They’re Wearing ‘Em Higher In Hawaii,” says Professor Amy Stiller, a musicologist at the University of Michigan. “Oh! And the other one that enjoyed great popularity was ‘Oh How She Could Yacki Hacki Wicki Wacki Woo.’”

Kalapana, Hawaii in the early 1900s. (Photo: Ulukau Hawiian Electronic Library/Public Domain)

These songs—and hundreds of others like them, from “Dear Old Dreamy Honolulu Town” to “O’Brien is Tryin’ to Learn to Talk Hawaiian“—were the strange product of an early phase of cultural appropriation, born in San Francisco and accelerated by the songwriters of New York City’s Tin Pan Alley. People couldn’t get enough of them, and even though you (probably) won’t be hearing them at a barbecue anytime soon, their legacy affects how Americans view the Aloha State to this day.

In the early 1900s, Hawaiian musicians had developed a unique musical style, a combination of long-lived religious chants and hymns and the sounds of steel guitars, ukuleles, and other instruments originally brought over by European travelers. As music historian Charles Hiroshi Garrett details in Struggling to Define a Nation: American Music and the Twentieth Century, this music was beginning to make inroads on the mainland, thanks largely to a Broadway musical called The Bird of Paradise—which featured, in the words of the New York Times, a glowing volcano, some star-crossed lovers, and “the weirdly sensuous music of the island people.”

An ad for The Bird of Paradise, emphasizing its main draws. (Image: University of Hawaii at Manoa Library/Public Domain)

But the music style’s true ascent began with the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition. Technically meant to commemorate the completion of the Panama Canal, the PPIE, which ran in San Francisco for seven months, doubled as a prime showoff opportunity for companies, tourism boards, and other moneyed interests. The Hawaiian legislature earmarked $100,000 (about $2 million today) to build a themed pavilion—one that would, in their words, “exceed in beauty, interest, and educational value anything hitherto attempted by Hawaii.”

To this particular contingent at this particular time, a properly excessive pavilion required floor-to-ceiling flowers, pineapple samples, a giant backlit aquarium, and a statue of three surfers about to keel over. It also involved the Royal Hawaiian Quartette—four talented performers, led by steel guitarist George E.K. Awai, who strummed and sang a variety of Hawaiian hits while decked out in leis and surrounded by ferns.

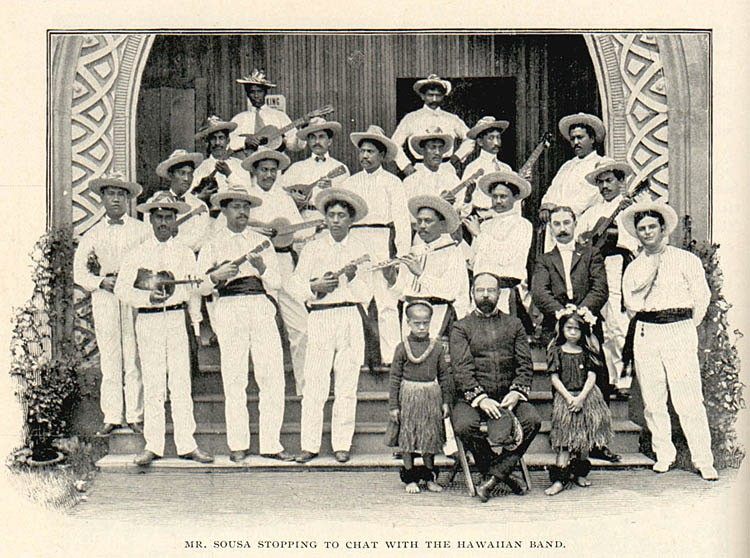

Although those who knew the real islands were less than impressed (one resident called it “nothing more than a collection of dead fish”), guests couldn’t stay away. “The strum of ukuleles and the tinkle of guitars … compelled entrance to the building,” one attendee wrote. During a special mid-June celebration, which also featured canoeing and a giant jewel-encrusted shell, the Hawaiian Quartette drew more fans than a neighboring concert by John Philip Sousa, America’s foremost military march composer.

John Philip Sousa hangs out with a Hawaiian ukulele band in 1901, just 14 years before his defeat. (Photo: Public Domain)

“So many people saw it, and they wanted to either buy a record, or buy a guitar and take some lessons,” explains Stillman. “And that’s when Tin Pan Alley songwriters looked at this and saw money to be made, and started churning out all of these silly, nonsense songs.” Tin Pan Alley, the Manhattan district that served as a kind of sonic parts dealer for the country, had already spent decades leaning into the country’s basest racial stereotypes. Its songwriters rose to this occasion, combining Hawaiian steel guitar lines with “Hawaiian” lyrics, like these, which open “My Honolulu Ukulele Baby:”

Down in Honolulu in the land of paradise

There’s a little hula maiden with dreamy goo goo eyes

She strums the ukulele and she dances in the breeze

And sings to me sweet songs of dear Hawaii…

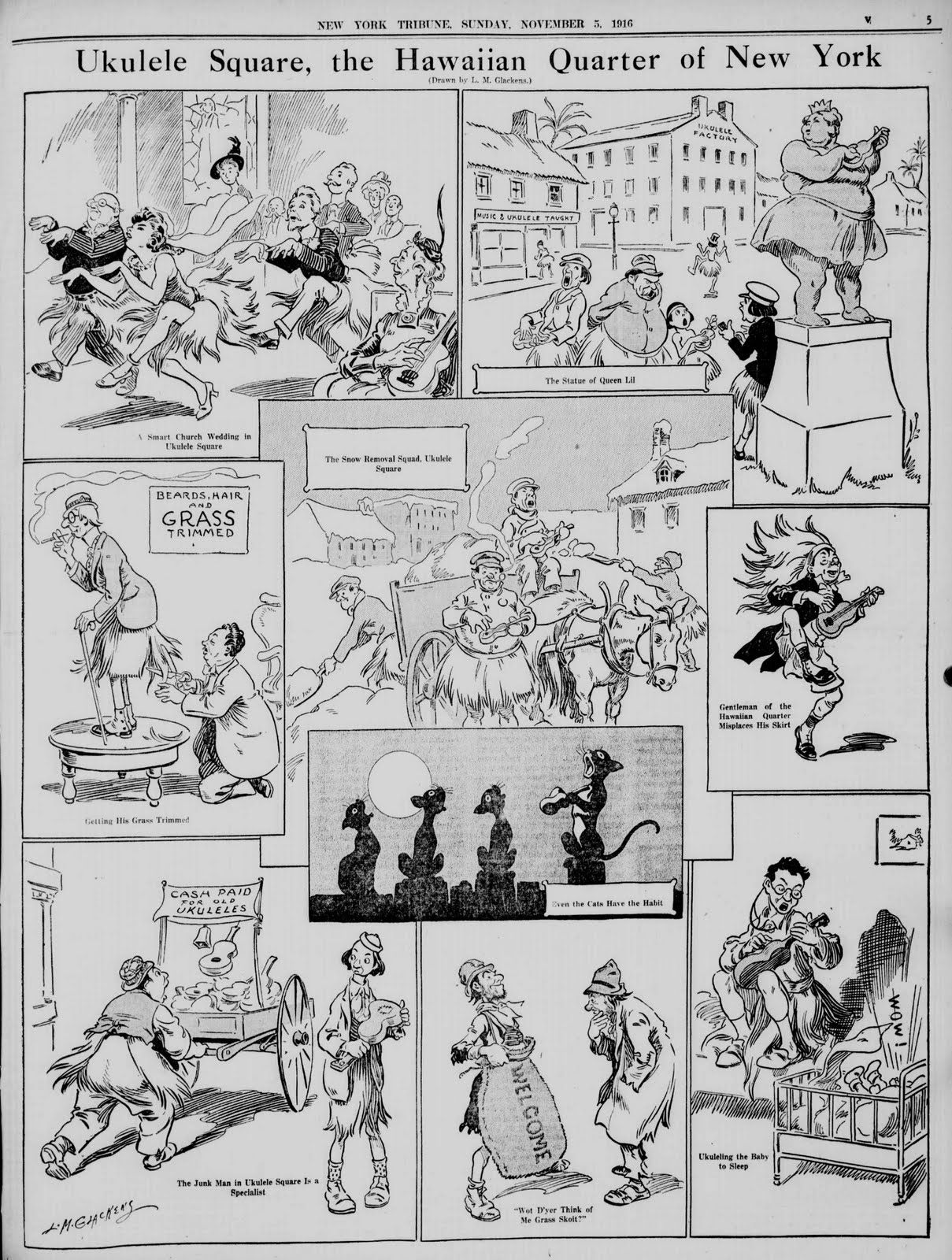

Pretty much every song had a hula girl, a beach, a uke, and not much else. It worked like a charm. “Every dealer knows that Hawaiian music has captured the fancy of the American public at the present time,” Edison Phonograph Monthly announced in July 1916. By September, they had doubled down, claiming “the biggest popular hits of this season are all Hawaiian songs.” According to one meta-song, “Honolulu, America Loves You,” addressed to the city and released in 1916, “You’ve made our poorest of families/Dance to your beautiful melodies/Our millionaires are playing ukeleles too…Up in Boston where they eat those beans/They know what Yacki Hula means.”

This sheet music cover from 1916 hits all the faux-Hawaii marks. (Image: Library of Congress/67/4573)

Backlash songs inevitably followed, like “The More I See Of Hawaii, The Better I Like New York” (which offers the excellent lyric “You’ve heard ‘em talk about the palm trees / They’re just a lot of false alarm trees”). These had little impact. Throughout the late teens, music fans across the country snapped up Hawaii-themed records and, especially, sheet music, which sported alluring, sunset-soaked covers. “It was a very small set of images that they were all capitalizing on,” Stillman says. “Some scholars summarize them as ‘sun, sand, surf, and sex.’” People didn’t just buy them for the covers: “Nearly all the young people in Berkeley seem to own ukuleles,” one California businessman reported in June of 1916, presciently.

Meanwhile, genuine Hawaiians capitalized on the trend, too, recording their own versions of the Tin Pan Alley cuts, alongside actual classics and original songs of their own. Over the years, Stillman says, this convergence summed to “a wildly mixed up thing that came to be known as Hawaiian music.” Take, for instance, a tune now called “Hawaiian War Chant,” which began as a love song written by a 19th-century prince. By the mid-1900s, “everyone and his grandmother had recorded it,” says Stillman. Along the way, they transformed it completely: “We had this love song with beautiful Hawaiian-language lyrics, suddenly becoming a war song and percussion showcase,” Stillman says. Lyrics about two lovers “embracing in the coolness” slowly turned into “ow way tah tualan, me big bad fightin’ man.”

A set of cartoons from 1916, mocking the so-called “Ukulele Craze.” (Image: Louis Glackens/Public Domain)

Stillman still hears “Hawaiian War Chant” after every UMichigan home game. But like all fads, the faux-Hawaiian trend eventually fizzled—Tin Pan Alley and its fans moved on to jazz, dance, and war songs, and Hawaiian communities around the world continued to create beautiful new styles of their own. “The Hawaiian language-based material has continued to persist in spite of it all,” says Stillman. “What’s really meaningful to Hawaiians is still there. But it’s not the Tin Pan Alley stuff.”

So if you get tired of Justin Timberlake’s sponsored troll song this summer, remember: it could be worse. Way worse.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook