2022 Was a Great Year for Mysteries

Our favorite head-scratchers, from a frightening stone to a curious cow’s tooth to maybe, just maybe, buried treasure.

This year, Atlas Obscura went hunting for answers to some of the surprising mysteries that have perplexed historians, scientists, artists, and treasure hunters for decades. We found debunked urban legends (the truth was far weirder), a new plant species, a very important misspelling, and, possibly, at least one elaborate prank.

The Strange, Awful Truth Behind Utah’s Eerie Stone Cross

by Greg Christensen

For decades a crudely constructed, 20-foot-tall cement and stone cross stood in a hollow on the northern outskirts of Kaysville, Utah. Marked with a large letter “K” in the center, it was known to locals as Kay’s Cross. It couldn’t be seen from any road and was on private property, undeveloped except for a few footpaths that meandered deep into the woods. Its secluded location, unknown origins, and proximity to the Kaysville Cemetery made Kay’s Cross a fixture of urban legend. But the truth, Greg Christensen discovered, is far more bizarre, involving the reclusive Kingston clan and a wandering religious zealot who claimed to be the reincarnation of Jesus Christ.

How Did a World War II Boat End Up at the Bottom of a California Lake?

by April White, Senior Editor/Writer

James Dunsdon’s hunt for the “ghost boat,” as he calls it, started with a rumor. The volunteer firefighter was working in the Shasta-Trinity National Forest in Northern California when he heard about a mysterious vessel that had been spotted somewhere along the lake’s winding, 365-mile shoreline. What he discovered was a World War II–era Higgins boat, a familiar sight to anyone who has seen images of the D-Day invasion. “It looked like it had just made a beach landing,” he says. The boat has been found but the real mystery remains: How did it end up in Shasta Lake, thousands of miles and eight decades away from the battlefields of World War II?

Was There Treasure Buried Under Lyon?

by Anna Richards

In 1959 road workers in Lyon, France, uncovered a network of 32 identical tunnels under the city, each about 100 feet long and each terminating mysteriously in a dead end. The arêtes de poisson, or “fishbones” as they became known, for their curious structure, remain an enigma more than 50 years later. Why did the Romans build these tunnels sometime between 100 B.C. and the first century? Numerous theories have already been debunked: The tunnels were not a water drainage system, a refuge, or a catacomb. But one popular hypothesis persists, that treasure was once buried under the French city.

A Botanical Mystery Solved, After 146 Years

by Gemma Tarlach, Senior Editor/Writer

Tianyi Yu studied the painting, a tangle of tropical plants crowded together in a riot of color produced in 1876 by prolific botanical artist Marianne North on a tour of Borneo. Yu, a young illustrator, was curious about the clusters of berries North depicted. These berries would solve a botanical cold case more than a century in the making. After extensive research, Yu discovered the plant was not a type of wild coffee, as once thought, but an entirely new species, now named Chassalia northiana, for the groundbreaking Victorian woman who captured its likeness in a natural setting.

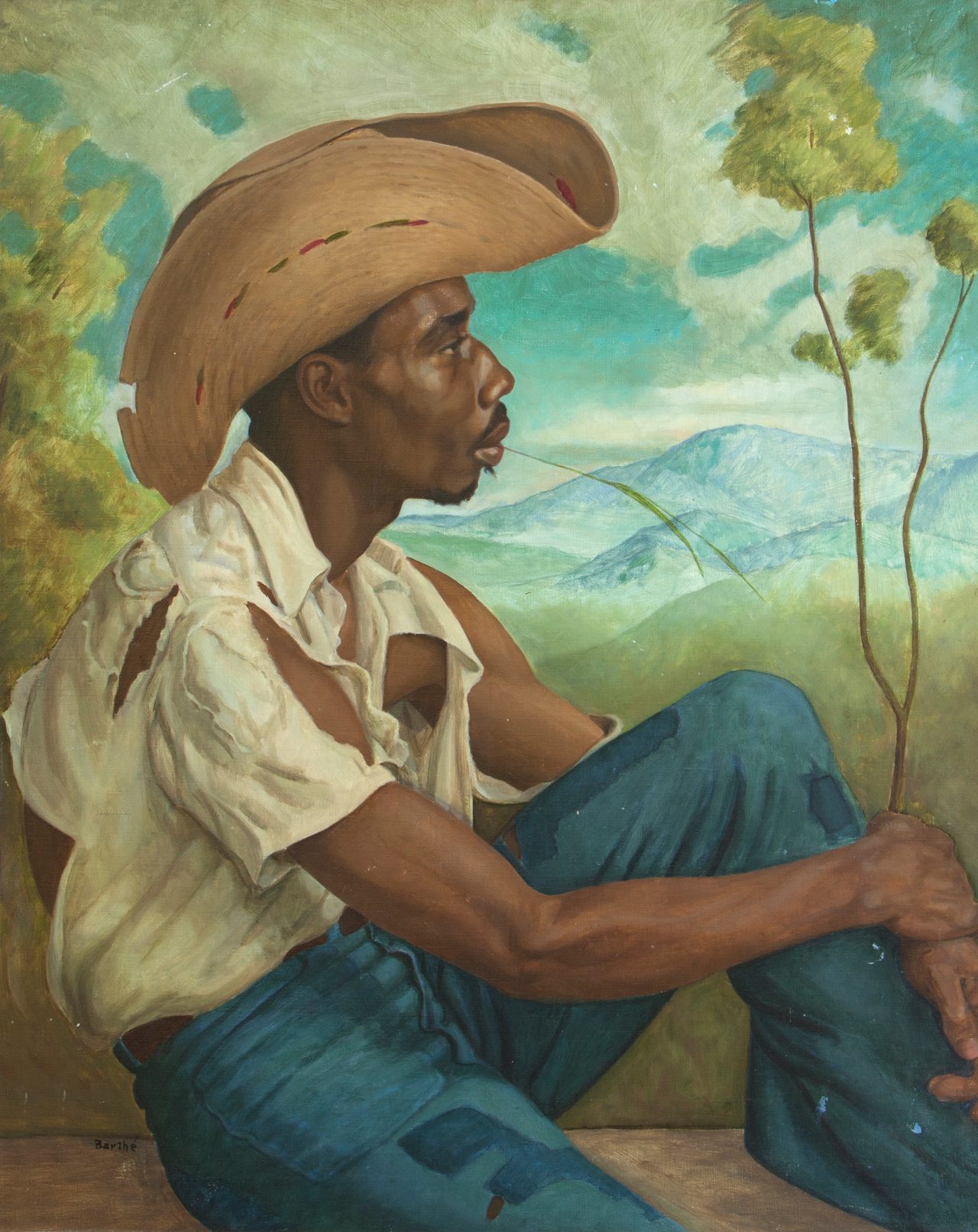

Solving the Mystery of the Seated Man

by Line Sidonie Talla Mafotsing, Editorial Fellow

In a 17th-century castle called Belton House just outside of the town of Grantham in Lincolnshire, England, there’s a mysterious painting of a Black man in profile. He’s wearing a straw hat and a torn white shirt, with his arms resting on his left leg. Seated in front of what looks to be a landscape painting, the model looks relaxed, perhaps even bored. At the bottom of the portrait, there is a signature that has long baffled art historians. Thanks to a simple typo, the artist and the subject of this stunning painting were a mystery, until now.

A Caribbean ‘Cow’ Tooth Could Solve the Mystery of the Chincoteague Ponies

by Gemma Tarlach, Senior Editor/Writer

The area of Haiti known as the Plaine-du-Nord is dotted with archaeological sites that chronicle millennia of indigenous Taíno settlements and, more recently, Spanish and French colonization. Among the hundreds of thousands of artifacts and bones unearthed was a partial tooth, about the size of a bottle cap, that connects a case of mistaken identity with scientific discovery, stirs long-simmering political and legal battles, and, most surprisingly, adds another layer of intrigue to the centuries-old mystery of the famed feral horses of the barrier island of Assateague, more than 1,300 miles to the north, writes Gemma Tarlach. Also, there are pirates.

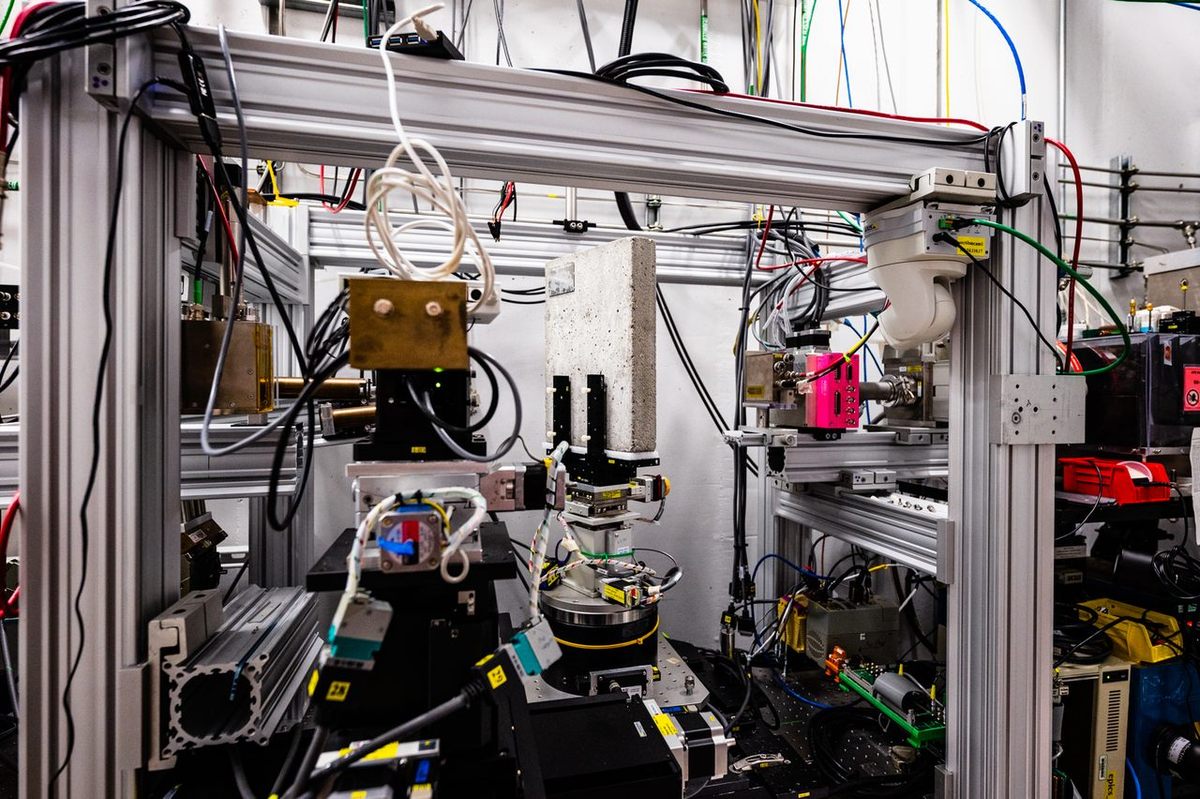

Can Science Solve the Mystery of the Concrete Book?

by April White, Senior Editor/Writer

The slab of concrete is more than a foot tall, 10 inches wide, and two inches thick. It weighs about 20 pounds, and it is cataloged in the University of Chicago’s library system as a book. This unusual tome, titled Betonbuch (Concrete Book), was “published” in Zurich, Switzerland, in 1971 by experimental artist Wolf Vostell. It is one of 100 copies he created by, Vostell explained at the time, encasing a 26-page booklet in concrete. Ot maybe it was all an elaborate, artistic prank. But scientists couldn’t just crack it open to find out.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook