7 Gorgeous Sea Maps From The Age Of Exploration

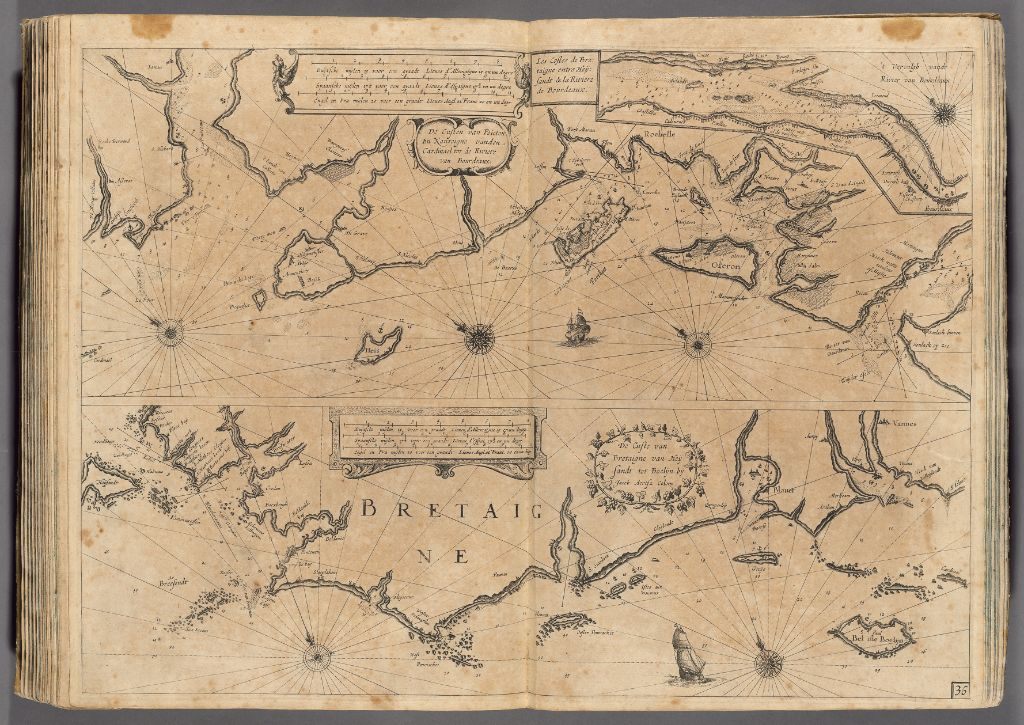

Lucas Janzsoon, Du Miroir de la Navigation, 1590. Image courtesy of the Harvard Map Collection.

Lucas Janzsoon, Du Miroir de la Navigation, 1590. Image courtesy of the Harvard Map Collection.

Ever since humans have felt the primal pull of distant shores, the sea has been integral to the way we travel and do business. But navigation in an era before satellites, GPS technology, and constant radio communication, was difficult and often fraught with risk.

That’s where the sky came in. Ancient explorers and traders first navigated based on the positions of the stars, aided by the oral reports of the sailors before them. By the late Middle Ages, as wayfinding technology improved, cartographers mapped the seas and coastlines, providing mariners with the ability to actually plot their routes and chart safe courses. At the onset of the Age of Exploration, in the early 16th century, both curious and financially-minded Europeans alike were rapidly pushing outward across the globe. These explorers, and the businessmen that followed, needed navigational guides, something to follow when they found themselves in strange territory thousands of miles from home.

Out of this exploratory push, many sea atlases were published for the most popular routes, providing sailors with the charts and directions. The Harvard Map Collection has put together a brilliant, interactive feature of some of the most astonishing atlases from the era. In it, you can zoom around the 500-year old charts, and even overlay them on top of a more modern map.

It’s truly fascinating—you can clearly visualize just how difficult it was to represent the shape and structure of the landscapes (and seascapes) without the benefit of looking at our blue planet from space. Below, we’ve selected a few of the most detailed and impressive maps for your viewing pleasure.

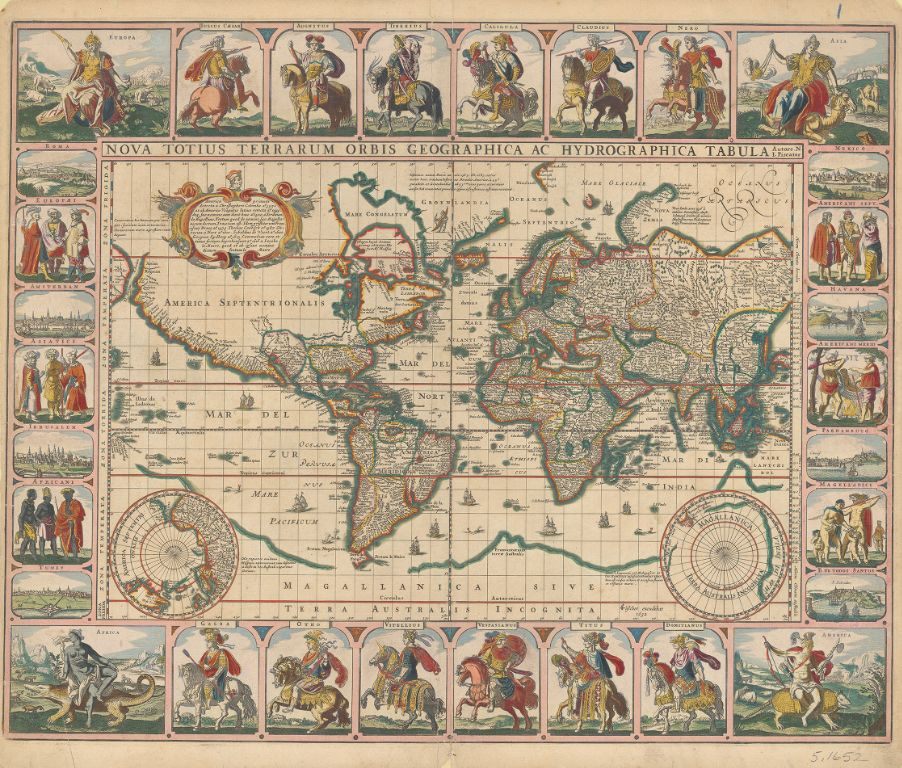

Frederik De Wit’s 1654 Dutch Sea Atlas. Image courtesy of the Harvard Map Collection

Frederik De Wit’s 1654 Dutch Sea Atlas. Image courtesy of the Harvard Map Collection

If you’ve ever wondered what the world looked like to a Dutchman in the mid 17th century, well, here it is. You can see he clearly got some things right: the general shape of the coastlines, and their relative distances in relation to one another are close. But this was well before North America and Siberia were fully explored, so it was anyone’s guess how far they extended.

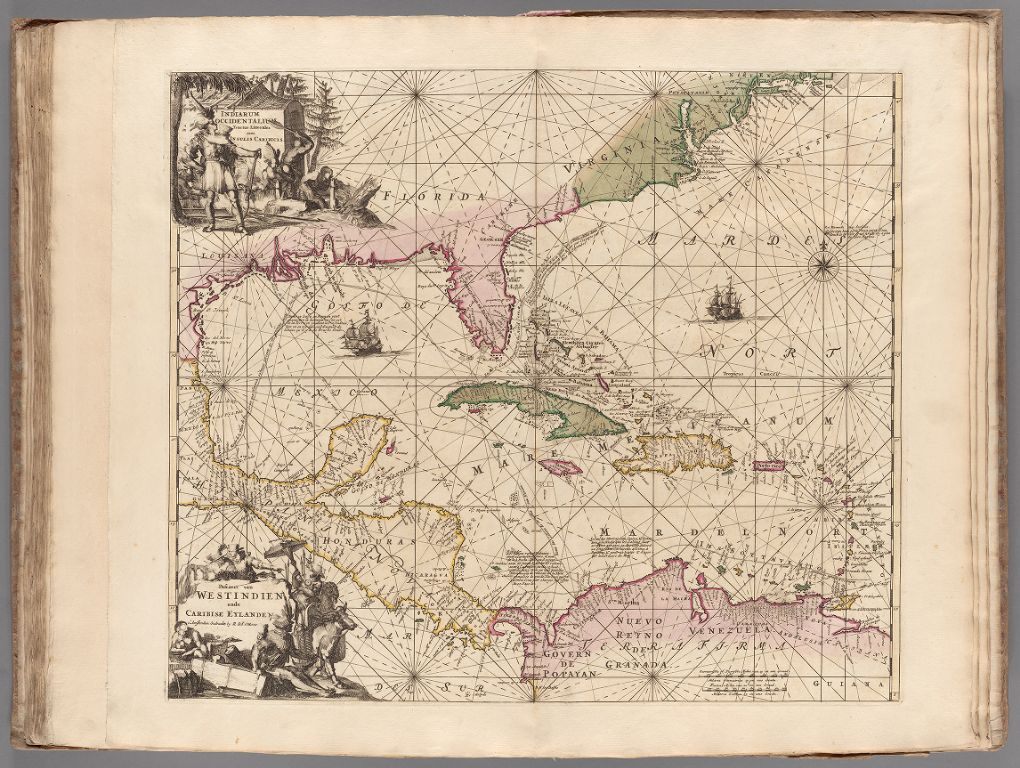

Louis Renard’s 1745 Atlas. Image Courtesy of the Harvard Map Collection

Louis Renard’s 1745 Atlas. Image Courtesy of the Harvard Map Collection

Seen here is the Caribbean Sea, according to Louis Renard’s 1745 atlas. Renard’s maps were used both for the armchair explorer, as well as more legitimate seafarers. Again, you can see some astonishingly accurate features, such as the locations of all the tiny islands dotting the Caribbean. This map is replete with some classic 18th century details, like the depiction of the savage North American tribes wielding bows and arrows.

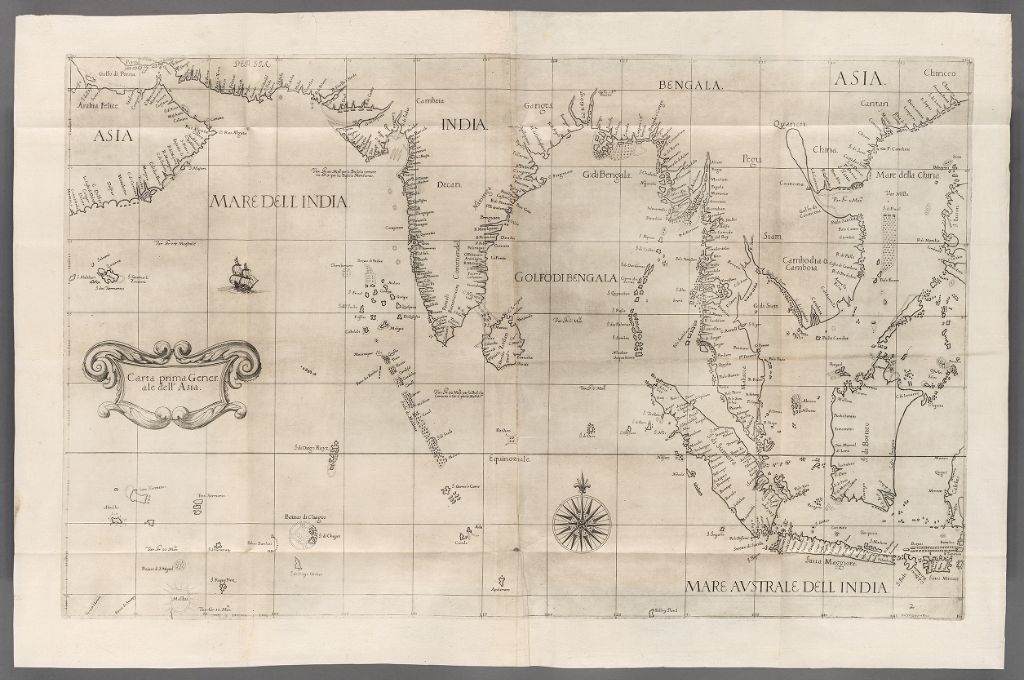

Sir Robert Dudley’s Dell’ Arcano Del Mar, 1646. Image courtesy of the Harvard Map Collection.

Sir Robert Dudley’s Dell’ Arcano Del Mar, 1646. Image courtesy of the Harvard Map Collection.

Sir Robert Dudley’s Dell’ Arcano Del Mar is considered one of the first “modern” maps. Sir Dudley’s atlas was one of the first to take into account the curvature of the Earth, and employed the Mercator Projection, in order to realistically display the distances between landmasses. Mercator projection maps were hugely advantageous over the charts of old, which were useful for close-quarters navigation, but provided useless over long distances.

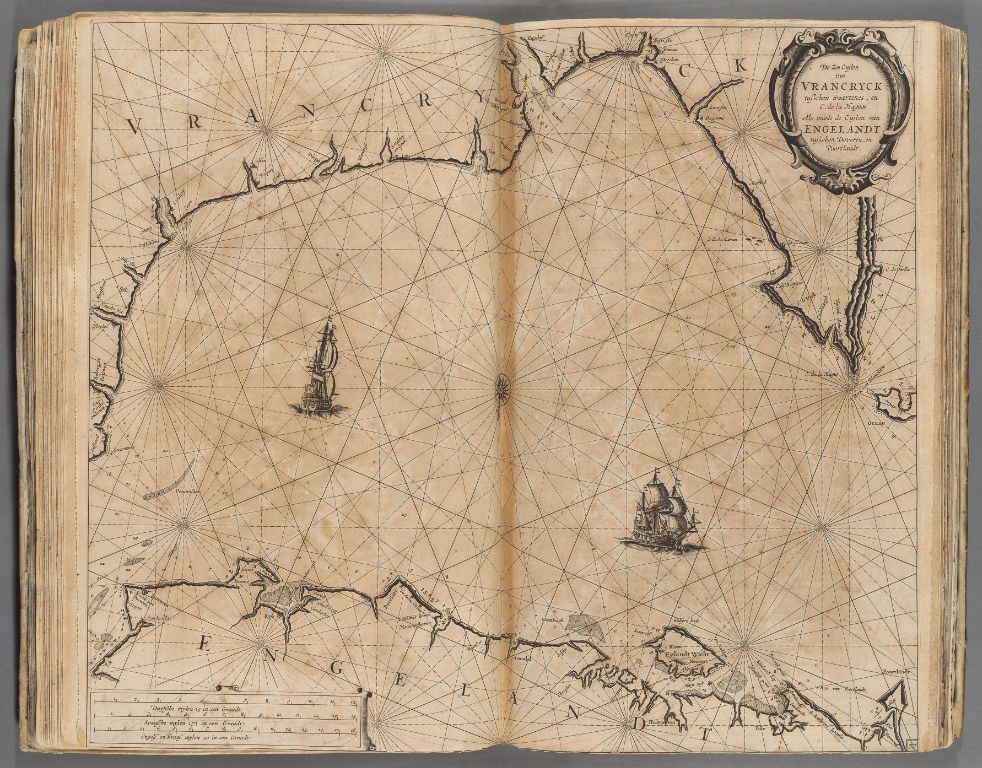

Pieter Goos, 1662. Le Grand & Nouveau Miroir Image Courtesy of the Harvard Map Collection.

Pieter Goos, 1662. Le Grand & Nouveau Miroir Image Courtesy of the Harvard Map Collection.

Pieter Goos’s 1662 sea atlas covered most of the Western and Northern hemisphere. Pictured here is the English Channel between France and Britain, along with the traditional shipping orientations.

Jacob Colom, 1633. Image courtesy of the Harvard Map Collection.

Jacob Colom, 1633. Image courtesy of the Harvard Map Collection.

Pictured here is the Bay of Biscay, on the coast of Northwest France. Jacob Colom’s sea atlas collection includes most of Europe, from the Baltic Sea, to the Atlantic coast of Spain.

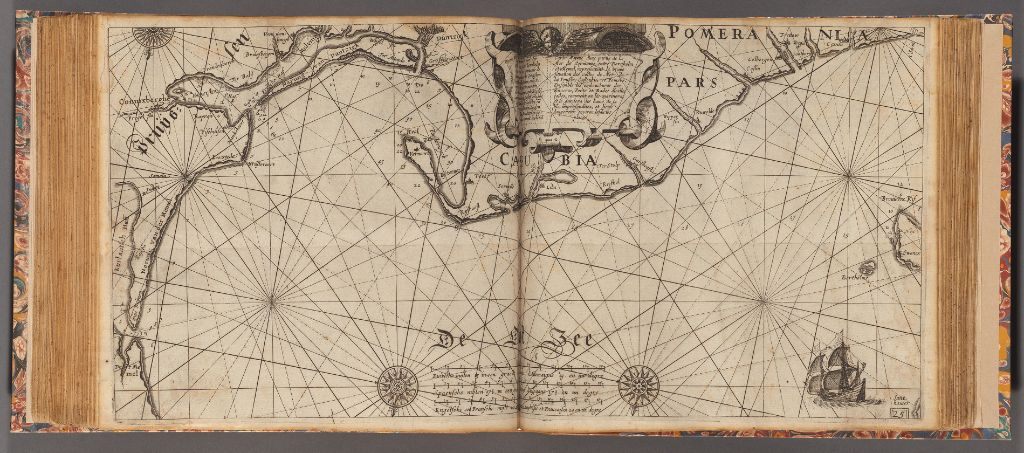

Willem Janszoon Blaeu, 1623. The Light of Navigation. Image courtesy of the Harvard Map Collection.

Willem Janszoon Blaeu, 1623. The Light of Navigation. Image courtesy of the Harvard Map Collection.

Willem Janszoon Blaeu’s 1623 The Light of Navigation contains 41 navigational charts for Europe’s coastlines. Pictured here is the northern coast of Poland, on the Baltic sea. Blaeu’s atlases were notable in that they combined features of celestial navigation with cartographic representation.

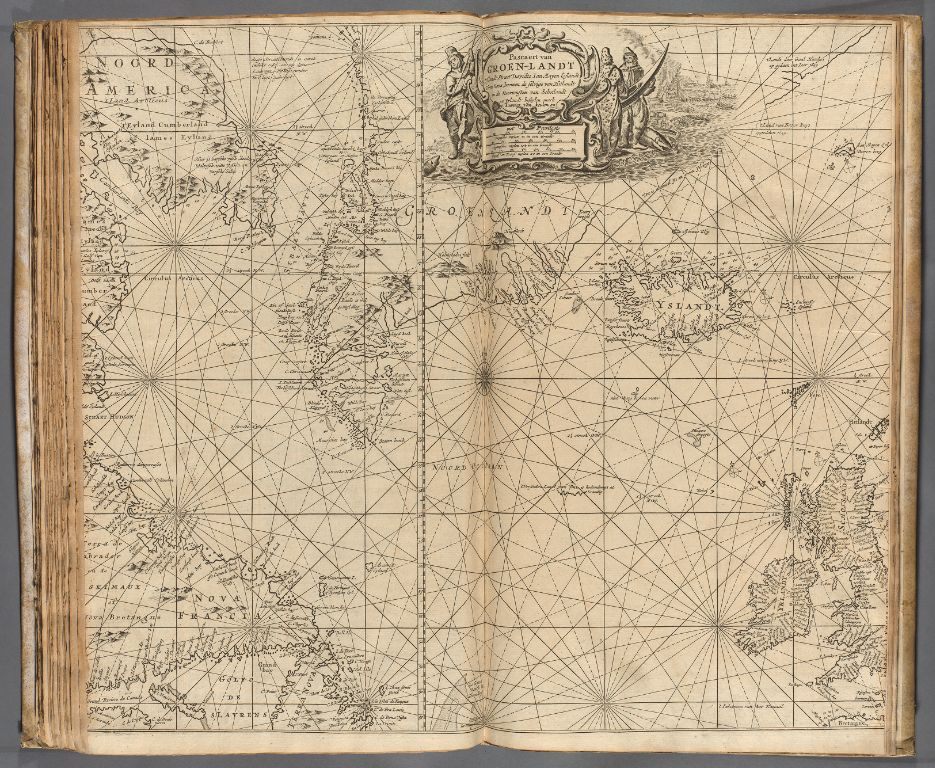

Gerard van Keulen, De Nieuwe Groot Lichtende Zee Fakkel, 1734. Image courtesy of the Harvard Map Collection.

Gerard van Keulen, De Nieuwe Groot Lichtende Zee Fakkel, 1734. Image courtesy of the Harvard Map Collection.

Gerard van Keulen’s De Nieuwe Groot Lichtende Zee Fakkel is arguably the most extensive collection of its era. Pictured here is the Northern Atlantic Ocean, with Iceland, Greenland, Ireland, and the northern coast of Labrador visible. Van Keulen’s maps were information heavy, and extremely useful to mariners endeavoring to cross the Atlantic.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook