A Short History of the Awkward Concession Phone Call

The first such call occurred in 1968.

On November 4, 1980, President Jimmy Carter went on television to concede to Ronald Reagan. The polls hadn’t closed in California yet, but it was obvious Reagan had won. Before his speech, Carter sent Reagan a telegram. “It’s now apparent that the American people have chosen you as the next president,” it read. “I congratulate you and pledge to you our fullest support and cooperation…”

Concession telegrams had been de rigueur for decades, but Carter added an additional flourish. He gave Reagan an unexpected call. The president-elect had just gotten out of the shower, and he picked up the phone in the bathroom, “with a wrapped towel around me, my hair dripping with water,” to accept Carter’s congratulations.

Thus, in his eagerness to show himself a graceful loser, Carter enshrined the awkward concession phone call in American election tradition.

In these final weeks of the 2016 election, reporters have asked if Donald Trump if he’ll concede, in the event of a Republican loss, and the answer hasn’t been exactly clear. But if the loser of tonight’s election doesn’t pick up the phone to congratulate the winner, it’ll be seen as a dramatic, petty snub. “The loser alone can truly congratulate the winner,” writes historian Paul E. Corcoran.

Nobody likes making the concession phone call: in the last election, President Obama, “unsmiling…and slightly irritated when it was over,” reportedly didn’t even enjoy receiving the call from Mitt Romney. But since Carter, it’s been unavoidable.

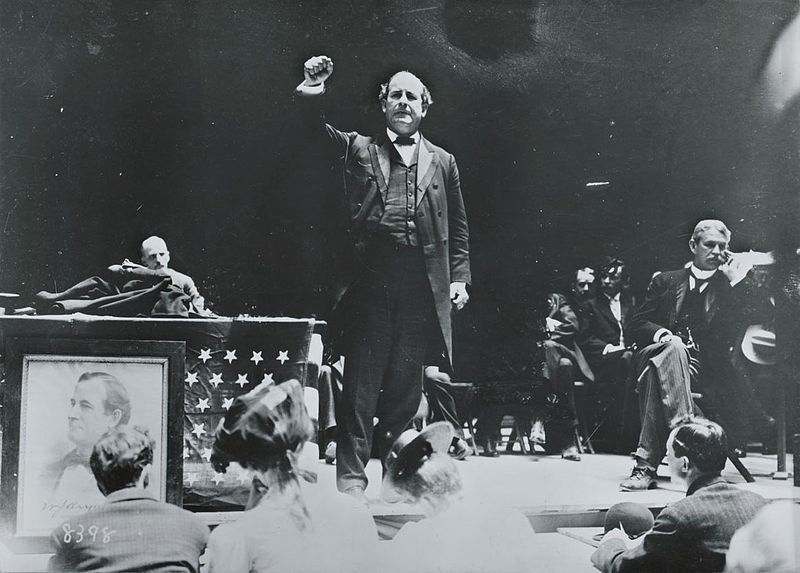

Presidential candidates didn’t always concede elections: the practice only goes back to the late 1800s. Democratic nominee William Jennings Bryan was the first candidate to send his opponent a concession telegram, and by 1916 it was expected that the election’s loser would write to the winner. Timeliness was expected as well: Woodrow Wilson was miffed that his opponent that year, Charles E. Hughes, didn’t send him a note until weeks after the election.

Four-time New York Governor and Democratic presidential candidate Al Smith is sometimes given credit for the modern routine: In 1928 he sent Herbert Hoover a congratulatory message but also gave a public concession speech on the radio. In 1940 Republican nominee Wendell Willkie’s concession speech was the first to be televised; in 1944, Franklin D. Roosevelt was insulted when Thomas Dewey never sent him a telegram congratulating him on his victory.

The defeated candidates would often read the telegrams they sent as part of their concession speeches, and sometimes those missives were used to make a political point. Goldwater wrote to Lyndon B. Johnson that the Republican Party “remains the party of opposition when opposition is called for. There is much to be done with Vietnam, Cuba, the problem of law and order in this country, and a productive economy.”

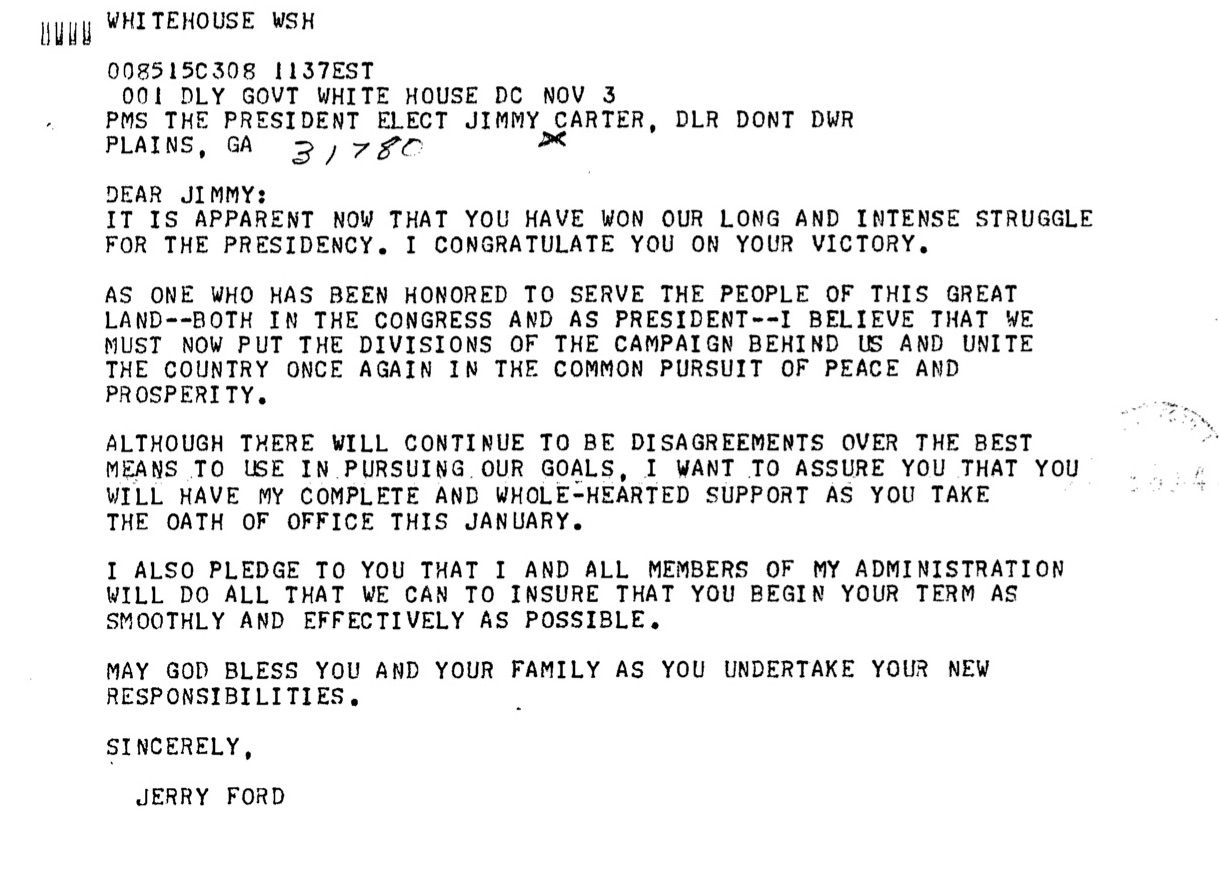

Usually the messages struck a note of reconciliation, like Ford’s to Carter, in 1976:

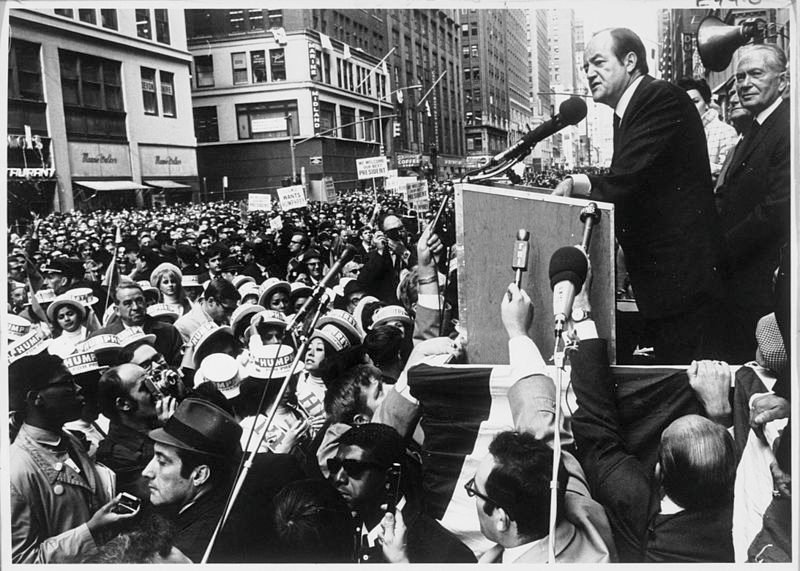

By contrast, the concession phone call happens in private; the candidate rarely reports what happened verbatim. Carter didn’t inaugurate the practice; after losing to Nixon in 1968, Vice President Hubert Humphrey both sent a telegram and picked up the phone. Nixon was known for being a sore loser, but he was a gracious enough winner. “I know how it feels to lose a close one,” he told Humphrey.

In 1972, though, Democratic presidential nominee George McGovern couldn’t bring himself to actually talk to the hated Nixon when he lost. He only sent a telegram. (Humphrey actually called Nixon again, to congratulate him on his re-election.)

Since Carter, though, the call has been expected. When former Democratic Vice President and nominee Walter Mondale called Ronald Reagan, the sitting president was fully dressed. Democratic candidate Michael Dukakis called George H.W. Bush to “congratulate him on his victory.” George Bush, Sr., gave Bill Clinton “a generous and forthcoming telephone call, of real congratulations.” Four years later, Bob Dole called Clinton, and he reported in true Southern fashion that, “We had a good visit.”

Al Gore infamously called George W. Bush to concede—then called back to rescind. Democratic nominee John Kerry waited until the day after the election, after a long night of vote-counting in Ohio, to call Bush and congratulate him. Republican John McCain said calling Barack Obama to congratulate him on his victory was “a honor.” (Classy!) Mitt Romney called the president and told him he had done a good job at turning out his voters. (Less classy.)

This cycle, even the day before the election, reporters were hearing that Donald Trump hasn’t decided what tone a concession might take, if he has to concede. It’s hard to imagine how painful it would be for Hillary Clinton to make that phone call, too. Perhaps this cycle, the candidates will update the form of the election concession once again. Telegrams are too old-fashioned to make a come-back, so instead of a concession phone call, should we expect a concession tweet?

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook