In 1972, Two Women Ran For President. It Didn’t Go Well.

Even feminists hesitated to support a female candidate.

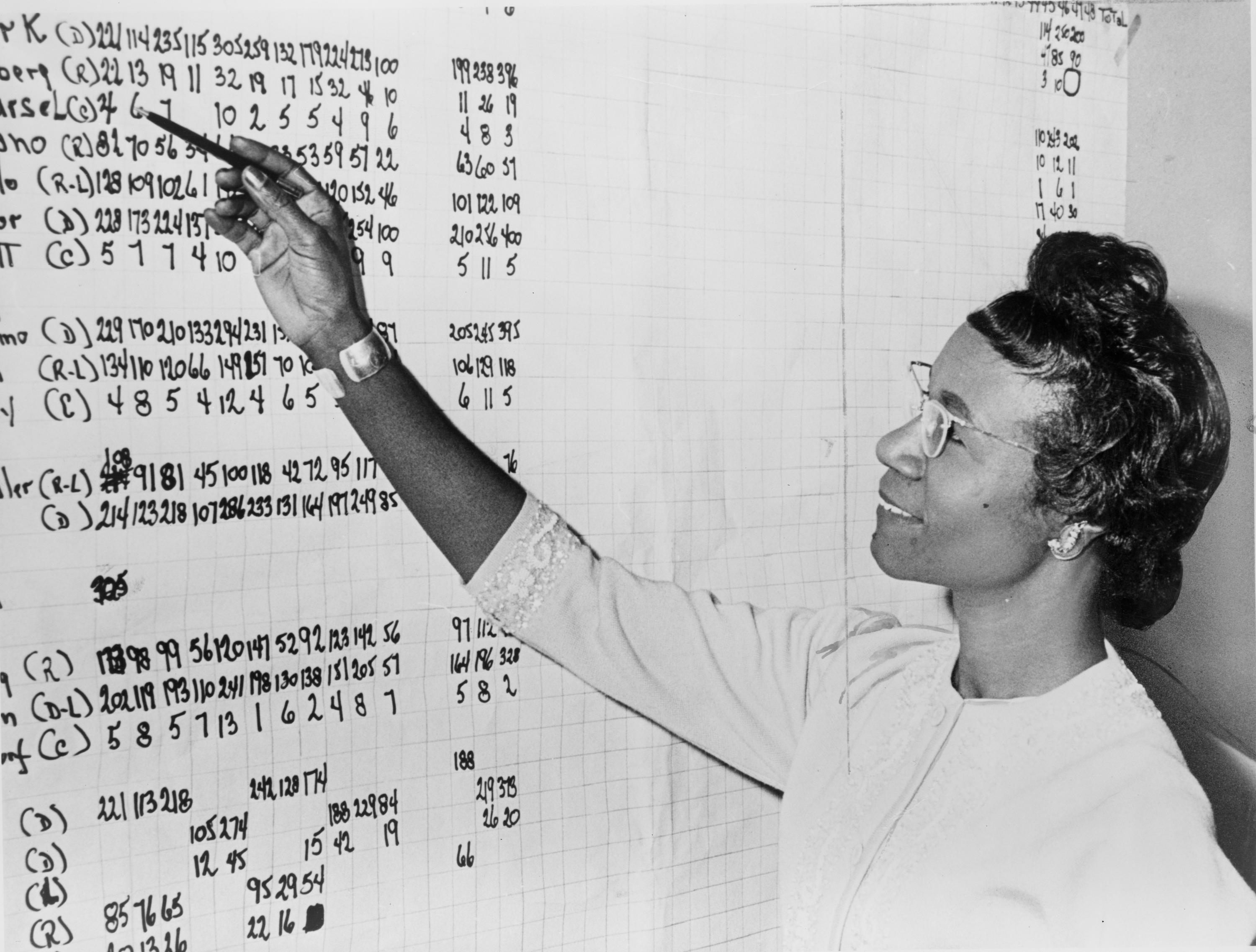

Shirley Chisholm. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Here’s one way to measure progress.

In 1972, there were two women who ran national campaigns to be President of the United States. Shirley Chisholm became the first woman (and the first black person) to be entered into nomination for the Democratic presidential ticket; she came in fourth. Another woman, Linda Jenness, was the Socialist Workers Party’s presidential candidate; at 31, she could not legally have become president even if she had won.

In 2016, there are two women running national campaigns to be President of the United States, and they will be their party’s nominees in the November election. Hillary Clinton will lead the Democratic ticket. Jill Stein will lead the Green Party ticket. (There’s even a push, among certain progressive voters, to choose “Jill not Hill.”)

It’s more common for women to run for president than anyone usually acknowledges, but usually they represent small parties and are ignored by both media and votes. 1972, the year Richard Nixon was reelected, was one of the banner years for female presidential candidates, but they still had to fight hard to be taken seriously.

Jenness was a secretary from Atlanta, active in leftist politics. She and her running mate, Andrew Pulley, who was 21, ran an issue-driven campaign: they advocated for socialized medicine, the repeal of all anti-abortion laws, free childcare facilities, limits on profits from the production of war materials, human rights for prisoners, and other democratic socialist positions. They also believed that they should be able to serve, if elected, despite being below the legal threshold of 35 years of age. “We think that constitutional requirement is ridiculous,” Jenness told one local paper.

Chisholm’s candidacy was more feasible, but most of her supporters did not take the campaign as seriously as she did. Even leading feminists did not throw the full weight of their support behind her: Gloria Steinem said she would support both Chisholm and Sen. George McGovern, the eventual Democratic nominee, who Steinem described as “the best white male candidate.” And once, introducing Chisholm, Betty Friedan said, “We will settle for no less than the vice-presidency.”

When Chisholm took the mic, she pushed back on Friedan’s limited ambitions. She did not want to be vice-president; she was running to be president. “I don’t want half-baked endorsements,” she said. “If you are going to be with me in a half-hearted fashion, don’t come with me at all.”

Being the first black person to be entered into the nomination didn’t help her, either. “Black male politicians are no different from white male politicians,” she said, meaning that they were just as skeptical of women taking power. “This ‘woman thing’ is so deep. I’ve found it out in this campaign if I never knew it before.”

That was 44 years ago—closing in on half a century. It took that long for the Democratic Party to go from voting, for the first time, on the nomination of a woman for president to actually choosing a woman as its presidential candidate.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook