Why an Alaskan Hospital Added Reindeer Pot Pie and Seal Soup to Its Menu

A state-spanning network of volunteers powers the program.

You’re not going to find jello cups on the menu at Alaska Native Medical Center in Anchorage, Alaska. Instead, patients and visitors choose between reindeer pot pie, smoked hooligan, birch sourdough biscuits with fireweed jelly, herring roe, salmon-belly or seal soup, and Eskimo ice cream (made with animal fat, fish oil, and berries).

Depending on the season, the hospital’s Executive Chef, Amy Foote, receives boxes of fiddlehead ferns and spruce tips trimmed in the late spring, coho salmon and halibut caught in late summer, cloudberries and blueberries picked and packed in the fall, and whale or other game meat in late winter. They are all donations, sent in by a state-wide network of hunters and gatherers who keep ANMC’s traditional foods program stocked with the ingredients that Alaska Natives have routinely enjoyed for generations.

“It blows my mind that we’re able to do this,” Foote says. “Why would people want to do this, donate to people they don’t know?”

But patients at ANMC weren’t always able to enjoy the comfort of familiar foods. Up until 2014, federal law prohibited foraged food due to concerns over safety. This meant ANMC’s menu was heavy on ingredients common to big-city grocery stores but rare in the small towns and remote villages where many of the hospital’s patients reside. It wasn’t until former Alaska Senator Mark Begich and retired Alaska Native physician Dr. Ted Mala lobbied for a specific measure on traditional foods to be included in the 2014 Farm Bill that ANMC could use non-commercialized traditional foods such as caribou.

Foote has been running the traditional-foods program since shortly after its inception. While her walk-in coolers are now full of indigenous ingredients (since 2015 she’s received more than 20,000 pounds of donations, and more than 70 percent of her recipes include traditional foods), in the early days of the program, every little donation was a huge victory.

That is because while Foote can buy ingredients such as salmon, both hospital fare and traditional-subsistence foods are still heavily regulated. Due to cross-contamination and foodborne-illness concerns, the hospital can’t accept anything too processed. That means, for example, that moose can be quartered, but not ground. And most wild fish and game can only be gifted or bartered—the result of an Alaskan law intended to prevent anyone from commercializing a basic food source. Selling foraged vegetables and berries, meanwhile, is not necessarily illegal, but is considered taboo. Custom dictates giving any extra to family or community elders.

Tim Ackerman is one of the many individuals who donates to the hospital. “They’re more apt to relax and not feel so out of place in the hospital when they have these foods,” Ackerman says. “It promotes well being. It helps the soul.”

A few years ago, while a buddy of Ackerman’s was in Anchorage for treatment, he overheard someone say that seal was the most requested, but least received, donation for the traditional-food program. “He said, ‘I know someone who can help,’ and I’ve been donating ever since,” Ackerman says.

The retired resident of Haines, Alaska, spends the short winter days pushing his kayak into the waters of the nearby inlet and paddling around in pursuit of harbor seals. He keeps some for himself and his family, but a larger share he donates and ships to Anchorage, more than 500 miles away, to be enjoyed by folks he considers his people, even if he doesn’t know them.

“It’s part of their diet. They need it to heal,” Ackerman says. “No big box stores can sell it. They need someone to help.”

You don’t necessarily need to be a patient at ANMC to try the fare. The gifts of nature, after all, are for everyone—it’s not uncommon for out-of-town visitors to swing through the cafeteria. Alaskans sometimes joke that the reason villagers come into Anchorage is to go to Costco and visit the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium campus, which houses and acts as a cultural and community hub.

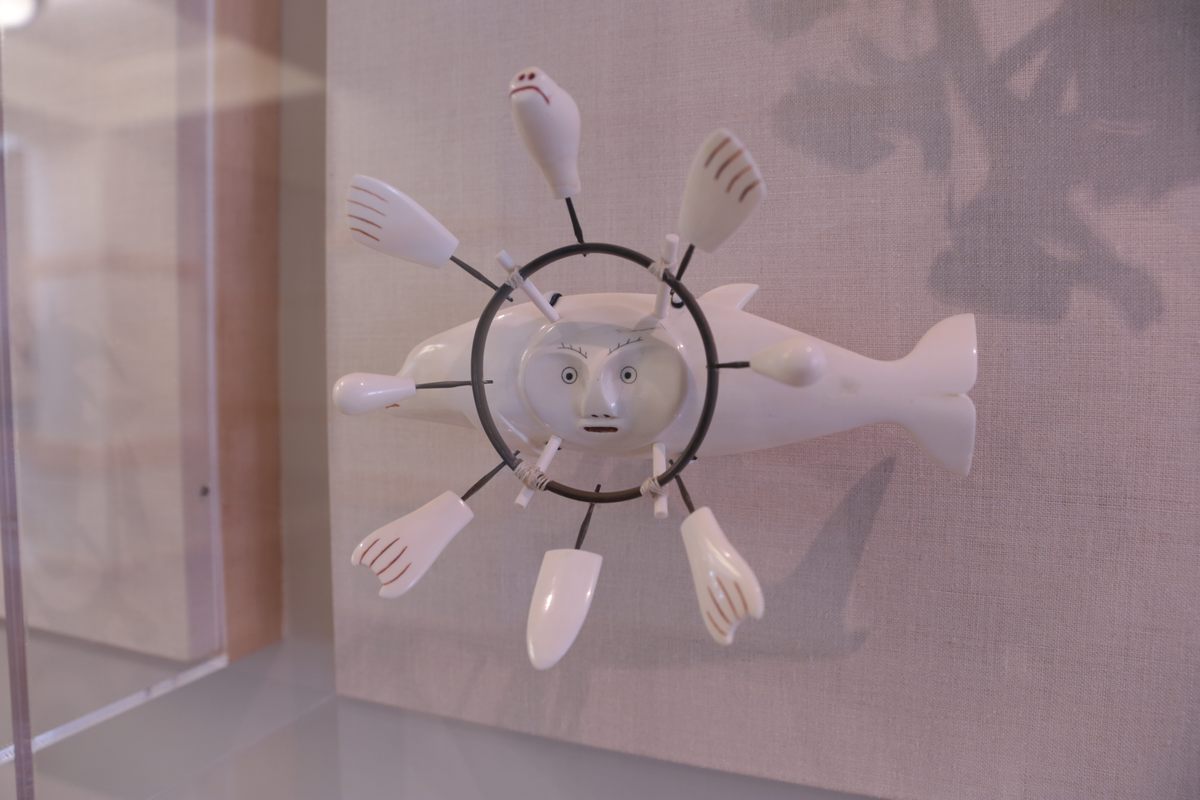

In non-pandemic times, Alaskans hang out on the campus, wander the hospital corridors to look at the thousands of pieces of museum-quality Indigenous artwork from across the state, and walk through the courtyard where hospital staff grow traditional vegetables such as rhubarb, currants, high bush cranberries, chocolate lilies, and blueberries. Started in 2018 as a college senior’s project, the garden is divided into three areas: tundra, bog, and birch forest.

“It’s like the village within the city,” Foote says.

Foote credits the emphasis placed on caring for elders in Alaska Native culture and the belief that traditional foods have healing properties for the success of the program. Having overcome the obstacle of procuring donations, she’s now tasked with perhaps the greater challenge of crafting a menu that speaks to the tastes of the various tribal groups.

Alaska is so vast that it resembles the Lower 48 in the breadth of regional fare. How salmon is prepared and preserved in the kitchens of Ketchikan, an island in a temperate rainforest near British Columbia, differs wildly from how it’s cooked in Nome, whose shores kiss the same frigid sea as most of Eastern Russia. Often that means combing through recipes to find similarities and common ground, such as seasoning with sea salt and smoking the protein in long strips.

Foote had processed game meat prior to accepting the job at ANMC, but seal was initially beyond her scope. Knowing that one of the kitchen workers was a hunter, she approached him about helping her butcher the first one.

“He said, ‘Oh, I don’t know how to do that,’” Foote says. “He explained that he only hunted them, the women butchered them. I didn’t know there was the cultural role, so I went to some of the Elder women on the line and they were able to teach me a lot.”

Because Foote isn’t an Alaska Native herself, she says she leaned on the expertise of Alaska Native Elders, getting their recipes and feedback to make sure the meals feel right. This proved key, since many early patients were skeptical that they could order a dish from their remote village while in a big-city hospital.

One time while Foote was going room to room and dispersing seal soup, a patient asked if she’d made the soup herself. He seemed doubtful, but once she confirmed that she had sought the wisdom of Elders, he softened.

“He started sharing these beautiful stories about how he remembered harvesting seal and hunting and fishing and cooking on the shore with his family,” Foote says. “And we watched this person who didn’t feel good, who was a little skeptical, all of the sudden feel comfortable and calm.”

These touch points are even more important now during the pandemic, Foote says. Because guests aren’t allowed in patient rooms, hospital stays can feel more isolating. Having something familiar is important, so the cafeteria staff takes requests. And thanks to a state-wide effort to stock the hospital’s pantry, they’re now able to meet requests for seal soup just as gamely as for chicken-noodle soup.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook