The Arctic Explorer Who Pushed an All-Meat Diet

Vilhjalmur Stefansson wanted to prove a point.

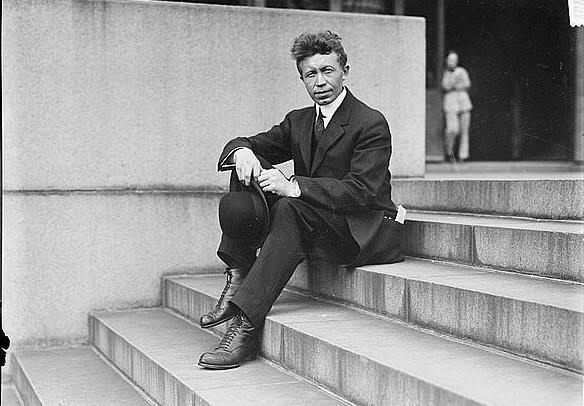

In 1928, Vilhjalmur Stefansson was already world-famous. A Canadian anthropologist and consummate showman, he promoted the idea of a “Friendly Arctic,” open to exploration and commercialization. Newspapers and magazines breathlessly covered his sometimes-deadly escapades in the Arctic, including his discoveries of some of the world’s last unknown landmasses, and, more controversially, a group of “blond” Inuinnait who he claimed partially descended from Norse settlers. But for a little while, another facet of Stefansson’s life drew media attention. While living in New York for a year, Stefansson ate nothing but meat.

Today, this would be known as a ketogenic, or a no-carb diet. It’s in vogue as a weight-loss tactic: The idea is that limiting carbohydrates, which are an easy source of energy, can make the body burn fat.

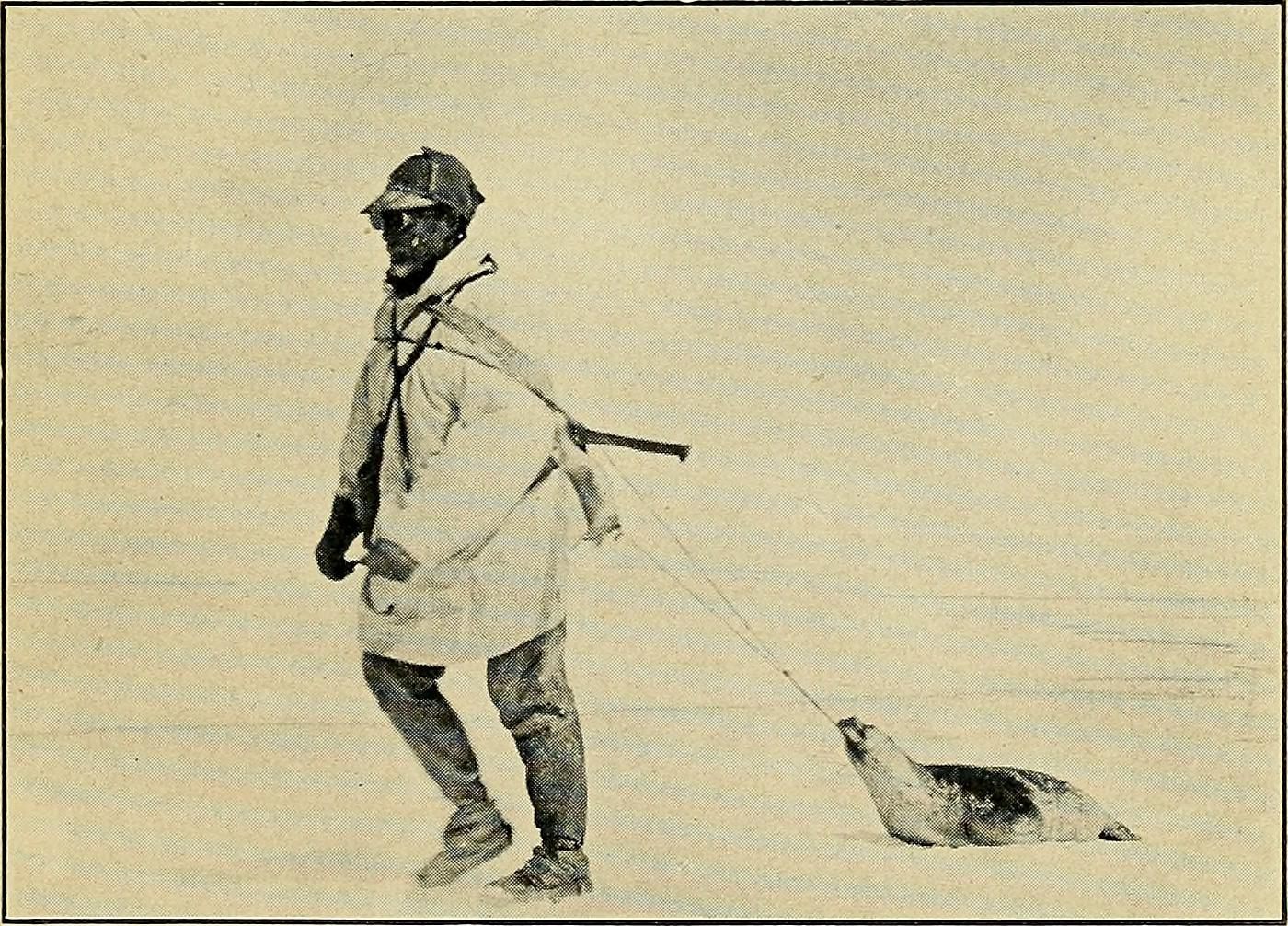

But Stefansson wasn’t trying to burn fat. Instead, he wanted to prove the viability of the Inuit’s meat-heavy diet. In the Arctic, people mainly ate fish and meat from seals, whale, caribou, and waterfowl, while brief summers offered limited vegetation, such as cloudberries and fireweed. Meals could be frozen fish, or elaborate treats such as the creamy fat-and-berry dish akutaq. Western doctors thought it was a terrible way to eat.

Even in the 1920s, a diet light on meat and heavy on vegetables was considered optimal. Vegetarians were more numerous than ever, and raw vegetables, particularly celery, took on a virtuous shine. This was the era of John Harvey Kellogg, famed for not only cereal, but his health resort in Battle Creek, where no meat was on the menu. (Stefansson was even a guest there, perhaps briefly swapping steak for snowflake toast.)

It’s now widely acknowledged that the Inuit subsistence diet is quite balanced. As biochemist and Arctic nutrition expert Harold Draper told Discover magazine, there are no essential foods, only essential nutrients. Vitamin A and D, so easily available from milk, vegetables, and sunlight, can also be obtained from oils within sea mammals (particularly livers) and fish. And fresh meats and fish, prepared raw, contain trace amounts of vitamin C, a fact that Stefansson was the first Westerner to realize. It only takes a little to prevent scurvy.

During Stefansson’s day, though, doctors, dietitians, and general opinion considered the meat-heavy diets of the Arctic peoples poor and improbable. Stefansson’s year of eating carnivorously was a high-profile attempt to prove them wrong.

Stefansson himself had only come around to the diet after an extended stay in the Mackenzie Delta of the western Arctic in 1906. When a ship carrying his supplies failed to materialize, he instead depended on the hospitality of a local family. At first, he roamed far and wide to build up an appetite for the plain roasted fish he received. “When I got home I would nibble at it and write in my diary what a terrible time I was having,” he wryly wrote later. But he gradually learned to enjoy the alternatively boiled, frozen, and fermented fish that he watched Inuvialuit women prepare.

It was during this first extended stay that he started to object to what he had been told about the Arctic diet, especially his peers’ horror over the “uncivilized” practice of eating fermented fish. “I tried the rotten fish one day, and if memory servers, liked it better than my first taste of Camembert,” he wrote. It wasn’t hard to notice that the diet had other benefits, too. “[I] did not get scurvy on the fish diet, nor learn that any of my fish-eating friends ever had it,” he wrote in Harper’s Monthly Magazine in 1935.

![Stefansson [right], four years before his meat-diet experiment.](https://img.atlasobscura.com/xsq3r9BKuzqZkq8qo0AQ0VnS11sKZdEbP3l-zA7eEPE/rs:fill:12000:12000/q:81/sm:1/scp:1/ar:1/aHR0cHM6Ly9hdGxh/cy1kZXYuczMuYW1h/em9uYXdzLmNvbS91/cGxvYWRzL2Fzc2V0/cy9jY2NiOWRjZi1i/ZTgwLTQ3YmUtYjY1/Ny1lYTgzZjBjODkz/YWU1MzNhZGI1MjVi/ZDg0ZTA5M2FfMTEw/NzB2LmpwZw.jpg)

Eating Inuit-style became Stefansson’s obsession. American and European explorers typically carried their own supplies with them, including fruitcake and whiskey. According to biographer Tom Henighan, Stefansson was (famously) more interested in eating what the Inuit were eating, and mostly hunted his own meat. This had a dual appeal: He didn’t have to bring along heavy supplies, and, as time went on and he suffered few ill effects, Stefansson became convinced the Inuit were on to something. As a result, Henighan writes, “he took issue with the medical dogma” that the best diet was extremely varied and featured the maximum amount of raw vegetables. In fact, he called those ideas the “fetishes” of dietitians. After retiring from Arctic forays in 1918, he estimated he had spent a total of five years living entirely off meat and water.

Stefansson even found himself defending the thesis that vegetables weren’t necessary for a healthy diet. “Stefansson Braves the Wrath of Vegetarians” was just one headline published during a flurry of media attention in 1924. “The common supposition is that a meat diet would lead to rheumatism, gout, and premature old age,” commented the anonymous writer, who also opined that while the chilly rigors of a life in the Arctic might make an all-meat diet possible, it wouldn’t be appropriate for someone living in a temperate or tropical zone.

So in 1928, Stefansson and another explorer began their culinary experiment. Checking into New York’s Bellevue Hospital, the two spent several weeks under constant supervision as doctors did blood tests and observed for signs of dietary distress. After a brief control period of a varied diet, the two men ate only fresh meat: The cuts included steak, roast beef, brains, and tongue, with calf liver once a week to ward off scurvy. Perhaps inevitably, the study was funded by the Institute of American Meat Packers.

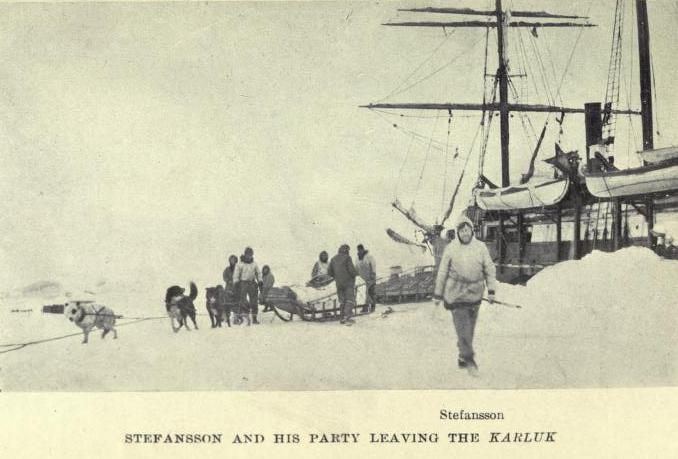

Despite the suspect funding, the study in New York was the culmination of Stefansson’s long interest in meat and the Arctic. For years, he had promoted the Arctic as a potential meat-producing paradise, capable of sustaining vast reindeer and muskox herds. His stance on living off the land led other explorers to try to debunk his self-sufficiency thesis: Explorer Roald Amundsen told the New York Times in 1921 that he was going to take seven year’s worth of food with him on the famous ship Maud when he went in search of the North Pole. Amundsen had a point, since during one expedition organized by Stefansson, most of its members starved to death.

While doctors condemned the diet as dangerous, Stefansson was defiant, attributing his increased vigor and “ambition” to his all-meat diet. Newspapers and magazines across the country ran stories on his experiment, contrasting it with the vegetable-heavy diets most doctors recommended. Soon, Stefansson left the hospital, having lost a few pounds, and continued his meat-eating endeavor from his New York apartment. Doctors examining the two men during the year-long trial reported that neither had heightened blood pressure or kidney trouble, the expected result of a carnivorous diet. The one thing lacking in their diet, Stefansson noted, was enough calcium.

Another conclusion Stefansson came to was that the protein he was eating wasn’t as important as the fat. He briefly flirted with “rabbit starvation,” a condition named for the fact that eating solely meat without sufficient fat can prove deadly. The human liver can only process so much protein sans fat without kickstarting the symptoms of protein poisoning: nausea, wasting, and death. Fat, and lots of it, is essential to the all-meat diet. Aquatic mammals are especially rich with fat, though. Recent studies point to genetics also playing a role in the Inuit aptitude for fatty, meat-filled diets, but as in Stefansson’s time as well as today, there remain questions about the relative healthiness of fats.

Lucky for Stefansson, fat suited him. Later in life, he cheerfully returned to a diet of meat and fat, washed down with Martinis. At dinner parties, he sometimes ate nothing but butter with a spoon. He died at the age of 82.

Despite his grandstanding, Stefansson didn’t think the all-meat diet was for everyone. It was expensive, and he knew there wasn’t enough meat in the world to feed everyone in such a way. But he always insisted that it was a viable, healthy diet.

Today, Stefansson is known more for his explorations, successful and otherwise. But some scholars appreciate him shining a light on the viability of local foodways, which had been dismissed as uncivilized and baffling. “Stefansson had no intention of recording Arctic food practices,” writes Arctic food historian Zona Spray Starks. “Yet he was one of the first explorers to credit Arctic native women with cooking knowledge.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook