El-Kurru’s Carved Graffiti Reveal Another Side of Ancient Nubia

From Kushites to Christians, an old site in Sudan has new stories to tell.

Anwar Mahajoub grew up in the village of El-Kurru, Sudan, along the Nile between its Third and Fourth Cataracts. Besides at its delta, which offers a flourish of emerald where the river meets the Mediterranean Sea, the Nile is almost entirely bordered by just a thin band of foliage, beyond which are the sepia sands of the Sahara. For centuries, the desert has obscured and protected the tombs of kings, riverside temples, even entire ancient cities. Mahajoub grew up next to one of these sites, so it was never obscured to him. Recent excavations there have made the tombs and world of ancient Nubia—specifically the Kingdom of Kush that ruled over it for hundreds of years—feel even closer.

“Since I grew up in the vicinity of [El-Kurru], the work in the archaeological site itself makes me feel closer not just to the past of childhood, but to the ancient past,” he says.

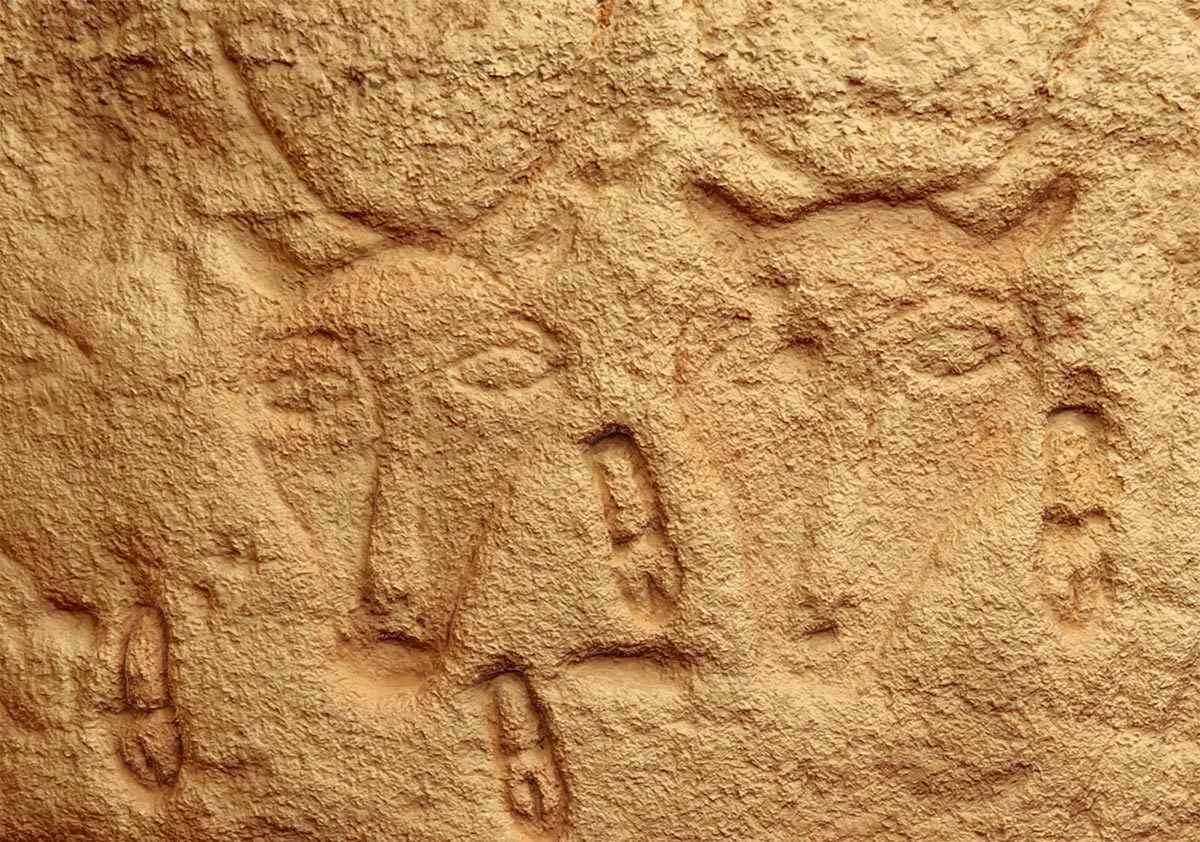

Recently, Mahajoub has offered his local knowledge to researchers from the University of Michigan on the International Kurru Archaeological Project, which has conducted some of the most extensive work there since the site was first excavated a century ago by American archaeologist George Reisner. El-Kurru consists of pyramid tombs from the seventh and eighth centuries B.C., as well as a pyramid and rock-cut temple built a few hundred years later. On those later structures, the team has documented nearly 1,000 individual carved graffiti spanning hundreds of years—some ancient Kushite, some more recent Christian, and all made as a form of worship.

“The more I know the historical facts about the site,” Mahajoub says, “the more I get attached to it.”

Some of the graffiti are merely scratched into the stone, while others are more sophisticated, almost like bas-relief. Many depict animals, means of transportation, and overt religious symbols. Some of the most common are merely gouged holes, which the archaeologists speculate were made to grind the temple’s stone and ingest it for spiritual and medicinal purposes.

“It could be that it was just easy to do, and you were making a sign that you were there,” says Suzanne Davis, head of conservation at the University of Michigan’s Kelsey Museum, “but there are also beliefs now in Sudan and parts of Egypt that if you consume part of the stone from an ancient, powerful monument, that it well help you.” As for the images, they would not have been easy to make, which, according to Geoff Emberling, an archaeologist with the University of Michigan who supervised the excavations, makes them all the more significant.

“Ancient images were carved and viewed in an environment where there were many fewer images than we’re used to seeing,” he says. “They were potent in part due to their scarcity.”

The earliest of the graffiti are carved on the temple, date to around the time it was built, in the fourth century B.C., and depicted Egyptian and Kushite motifs. The later Christian works were carved into the other structure, the pyramid, by pilgrims during the early medieval period, around the 9th or 10th centuries, near the time when the structure collapsed, centuries after the decline of the Kingdom.

In ancient Kush, Emberling says, an image of something—archers, giraffes, and vipers, symbols of the underworld—could invoke its presence, “a magical quality.” Some of the older images bear a resemblance to Egyptian gods and folklore, since the Egyptians once conquered Kush (and later, Kush conquered Egypt right back). The Christian iconography offers clear interpretations: numerous boats (which may indicate how the pilgrims arrived) and monograms that stand for certain saints and other Christian figures. Following the collapse of the Kushite empire in the fourth century, local kings had adopted Christianity. The Christian symbols then may have been learned from missionaries from the north. In any case, Emberling says, the fact that both traditions are present at a single place helps clarify the importance and history of the site.

Vast temple complexes and burial grounds like these typically are windows into the lives and deaths of the rich and powerful; the El-Kurru graffiti, on the other hand, reveals something about everyone else, including how they expressed their beliefs.

“Not only are these marks of a mobile population, a cattle culture,” says Emberling, “but they’re also the direct testimony of people who are not the elite.”

Photographs of the etchings are on view at the University of Michigan’s Kelsey School of Archaeology through March 2020. Davis hopes the exhibition shows visitors—almost all of whom will never visit El-Kurru—a different side of a civilization that thrived for hundreds of years.“If you look at what other museums have in their galleries from Kush, you’ll see really fancy things that belonged to kings,” she says. “It would be like learning everything about the United Kingdom from what’s inside Buckingham Palace.”

El-Kurru is far, far from Ann Arbor, but this increasingly complex story of ancient Kush is being told there as well.

“I am excited about the visitor center, which the team is working to establish in my village,” says Mahajoub. “It will provide a broader understanding of the site for the visitors, the local heritage of the village, and will help in the development of the village.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook