The First Woman to Thru-Hike the Appalachian Trail Alone Did It as a ‘Lark’

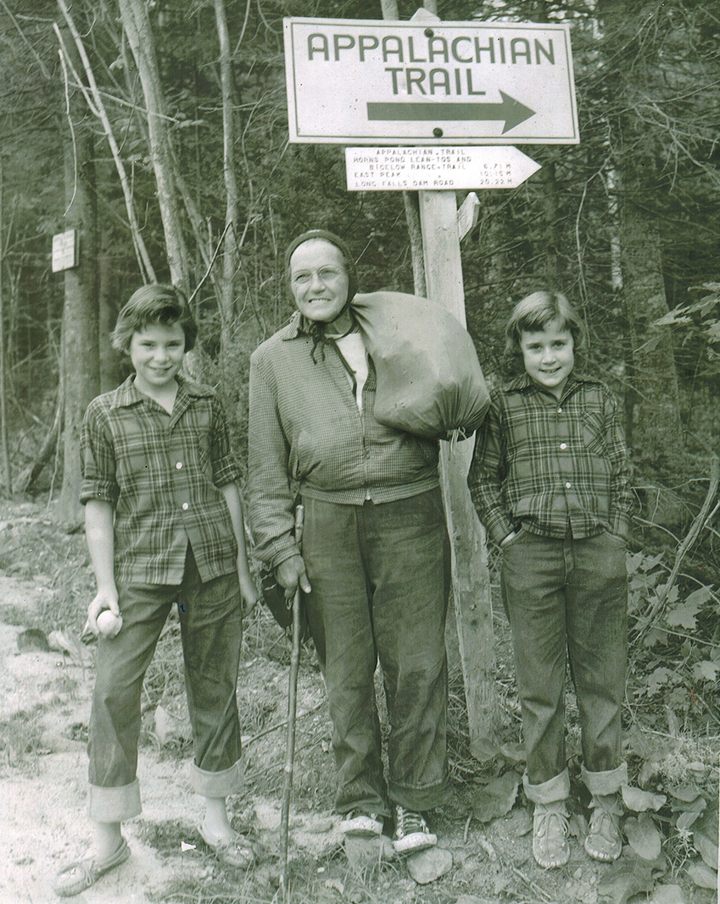

Emma Gatewood set out wearing sneakers, with a duffel slung over one shoulder.

This story is excerpted and adapted from The Appalachian Trail: A Biography by Philip D’Anieri, published in June 2021 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

On April 4, 1948, Army veteran Earl Shaffer set out from the southern end of the Appalachian Trail (AT) to, as he famously said, “walk the war out of my system.” When he finished at the northern terminus, Maine’s Mt. Katahdin, 124 days later, Shaffer became the first person known to have thru-hiked the 2,000 mile-plus trail that snakes its way up the mountainous spine of the eastern United States. Less than a decade later, a 67-year-old grandmother laced up not hiking boots but sneakers, and became the first woman to thru-hike the trail on her own*. While Shaffer’s journey of finding redemption on the trail is better known, Emma Gatewood’s trek is just as compelling: After a lifetime of dire hardship, she was simply drawn to the freedom of a long walk.

Gatewood, unlike most thru-hikers of the Appalachian Trail, was actually from Appalachia, the southern highland region defined by both its steep terrain and distinct social economy. She grew up among the Allegheny foothills of far southeastern Ohio, and her everyday environment had much more in common with that of West Virginia, just across the Ohio River, than with the agricultural flatlands and industrial cities of the rest of her home state.

She was born Emma Caldwell in Gallia County in 1887, the 12th of 15 children, and grew up on a succession of farms as her family moved repeatedly in search of better opportunities. For the Caldwells and the thousands of people who scratched out a living in the hills, unlike their counterparts in towns and cities, the outdoors was a workplace from which to wrest a livelihood, not a patch of scenery to admire and explore. At 18, she was earning 75 cents a week as live-in help when she met P. C. Gatewood. The two got married in the spring of 1907. Almost from day one of their marriage, according to her descendant and biographer, Ben Montgomery, Emma Gatewood’s husband viewed her as a possession, and violence as his means of control. After he hit her for the first time, according to Montgomery:

She thought of leaving him that day and that night and on into the next, but where would she go? She had no paying job, no savings, and her education had ended in the eighth grade. She couldn’t return home and be a burden on her mother, who remained busy rearing children. So she bit her tongue and stayed with P.C.

Surviving her husband and providing for her steadily growing family would define Gatewood’s married life for the next three decades. She raised 11 children, ran the household, and performed back-breaking farm labor. Through it all, she did whatever she could to protect herself and her children from her husband. She defended herself, she fought back, and she sometimes escaped to the woods, where the idea of refuge among the trees was no literary allusion, but an all-too-real matter of life and death. There were happy times as well. The children remembered their mother especially enjoyed taking them for long walks.

P. C. Gatewood was convicted of manslaughter after he killed a man in 1924. He was given a suspended sentence because of the court’s belief that he needed to be able to provide for his wife and children, but the restitution he was ordered to pay required selling off half the farm, and began a steady cycle of worsening economic fortunes for the family.

His violence toward Emma was a constant. In 1937, she left her younger children in the care of their adult siblings, and escaped to California, where her mother and two of her siblings lived. She corresponded with her children in letters that had no return address, and were carefully written to prevent P. C. from determining her precise whereabouts. In the end, she returned home out of obligation to the children, knowing that it put her again in harm’s way.

Not long after, P. C. moved with Emma and the three youngest children, aged 11 to 15, to a small farm on the West Virginia side of the river. In 1939 he managed to have Emma arrested after a fight between the two of them that left her badly battered. But the event turned out to be the beginning of the end for the Gatewoods’ marriage, and P. C.’s presence in Emma’s life. In early 1941, after more than 30 years of marriage, Emma Gatewood secured a divorce. Now in her early 50s, she would set about building a new life on her own terms. Those terms would eventually include going for several very long walks.

By the end of World War II, Emma had moved back to Ohio. Free to fashion a life on her own terms, she spent the next several years moving around to different jobs and arrangements, tending to sick relatives, and working in healthcare. At some point, she came across a 1949 article in National Geographic about the Appalachian Trail. It mentioned that a young man from Pennsylvania, Earl Shaffer, had become the first to hike the full length of the trail in a single trip.

In 1954, Gatewood, then 66 and apparently knowing nothing more about the trail than what had appeared in National Geographic, made her own decision to hike the full AT. She would never provide a singular answer as to why she was drawn to a thru-hike, beyond the fact that the trail sounded attractive to her, and she appreciated having the freedom to do as she pleased. The National Geographic article had organized its overview from north to south, and in July Gatewood arrived at Baxter State Park in Maine to begin her trek. Though her first day on the trail was a success, she quickly ran into trouble. On just her second full day of hiking, she inadvertently left the trail, one of the most dangerous situations for AT hikers. In the deep woods of Maine, being just a short distance off a trail can render it completely invisible, at which point the sea of surrounding trees becomes uniform and directionless, and disorientation quickly sets in. After two nights in the wilderness, and breaking her glasses, Gatewood somehow managed to rediscover the trail and return to where she’d started. With the strong encouragement of park rangers, including a ride to the nearest train station by the park’s superintendent, Gatewood called off her hike and returned to Ohio.

The next spring she tried again, this time heading north from Georgia. As she had the previous year, Gatewood told no one, including her own family, what she was up to. She didn’t want them to worry, or to try to dissuade her.

From the start, Gatewood made little distinction between the trail she was hiking on and the larger territory she was walking through. She sought food and shelter from the world around her, whether that was picking berries on the trail or asking to spend the night on nearby farms. Rather than outfit herself in special gear, she wore sneakers and slung her few belongings in a duffel over her shoulder. Gatewood had spent virtually her entire life in a working Appalachian landscape, getting around by foot, making do with what was at hand. Her hike on the AT would play out as an extension of that life, an indulgence in something that she enjoyed, rather than a self-conscious expedition into nature.

Her first night, she lost the trail but came upon a house whose owners let her spend the night, and she hiked back in the morning. The second night, she used an abandoned shack near the trail for shelter. Later in Georgia she overnighted in a church. Another night, she was told by a man that she couldn’t stay on his property, because she belonged with her family and not out hiking on her own.

Day in and day out, she relied on her own grit and wits to get by, and on the generosity of others. As was the case with Shaffer, word of Gatewood’s passage over the trail began to precede her, and local reporters caught up with her to write stories. One reporter took an especially keen interest. As Gatewood approached Bear Mountain in New York, Mary Snow, who covered women’s sports for Sports Illustrated, arranged to hike along with her for about five miles, bought her dinner, and paid for a cabin.

Unlike much of the other coverage, which portrayed Gatewood as an eccentric, Snow’s story, a short back-page article, focused on the seriousness of the challenge she had undertaken:

Mrs. Gatewood, alone and without a map, began following the white blaze marks of the trail early in May, and this week from Connecticut’s Cathedral Pines, Grandmother Gatewood could look back on 1,500 miles of the best and worst of nature. She had carefully avoided disturbing three copperheads and two rattlesnakes on the trail, flipped aside one attacking rattler with a walking stick. When caught without nearby shelter she had heated some stones and slept on them to keep from freezing. For snacks Grandma nibbled wild huckleberries, used sorrel for salad and sucked bouillon cubes to combat loss of body salt.

When Gatewood got to Baxter State Park, she was met by both Snow and the woman who had reported on the conclusion of Shaffer’s hike seven years earlier, Mrs. Dean Chase. (Chase was known, as many women were at the time, by her husband’s name. Snow’s articles on Gatewood went without a byline.) The two women would accompany Gatewood off and on for the next several days, but she climbed Katahdin alone, for the second time in just over a year, to complete her hike on the morning of September 25, 1955.

Asked why she undertook the trip, Gatewood answered, “Because I wanted to,” and because of the alluring things she had read about the Appalachian Trail. The reality was a disappointment. “The article told about the beautiful trail, how well marked it was, that it was cleared out and that there were shelters at the end of a good day’s hike,” she said. “I thought it would be a nice lark. It wasn’t.”

Despite her disappointment, and settling back into her Ohio life, in the spring of 1957, Gatewood flew to Georgia again and thru-hiked the AT for the second time in three years, finishing a few weeks before her 70th birthday. In 1959 she walked along roads that followed the old Oregon Trail, from Independence, Missouri, to Portland, Oregon, her progress tracked in newspapers, and the crush of onlookers near the end leaving her so frustrated that she hit one photographer with her umbrella. In 1964, at 77, she completed a section hike of the AT, the last of a series of separate such trips over the years, marking the third time she had walked the full length of the Appalachian Trail.

During this period, AT thru-hikers remained rare. It was only in the late 1960s, and accelerating in the ’70s, that the popularity of hiking soared, to the point that hundreds of would-be thru-hikers were setting out from Georgia’s Springer Mountain each spring.

Earl Shaffer’s 1948 hike came to serve as the origin story for a thru-hiking culture that was playing a bigger and bigger role in the life of the AT itself, portrayed as a wilderness experience where backpacking skill and know-how provided entry to a separate, higher realm of nature. But Gatewood showed that the AT could be hiked in concert with the world of buildings and people that permeated it, not necessarily in opposition to them, and that it was a stage not just for the heroism of a young man, but for the mundane getting-by of an old lady. Yes, it could be the object of a years-long quest to re-create oneself. But it could also be “a lark,” taken up at the suggestion of nothing greater than a chance encounter with a magazine article.

Gatewood continued to hike and travel until the end of her life. Beginning in 1967, she led an annual winter hike along a trail, now named after her, in Ohio’s Hocking Hills. The hike drew 2,500 participants in 1973, not long after which Gatewood embarked on a bus trip around the United States and parts of Canada. Within days of returning home, she fell seriously ill, and her condition quickly deteriorated. Emma Gatewood died in June 1973, at the age of 85.

*Correction: This excerpt previously did not clarify Emma Gatewood was the first woman to thru-hike the Appalachian Trail alone. In 1952, Mildred Norman and a male hiking partner completed a “flip-flop,” hiking part of the full trail in one direction, then traveling to the other end and hiking the remainder in the opposite direction.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook