The Conqueror Who Longed for Melons

Many Indian dishes can be traced back, indirectly, to a 16th-century, food-obsessed ruler named Babur.

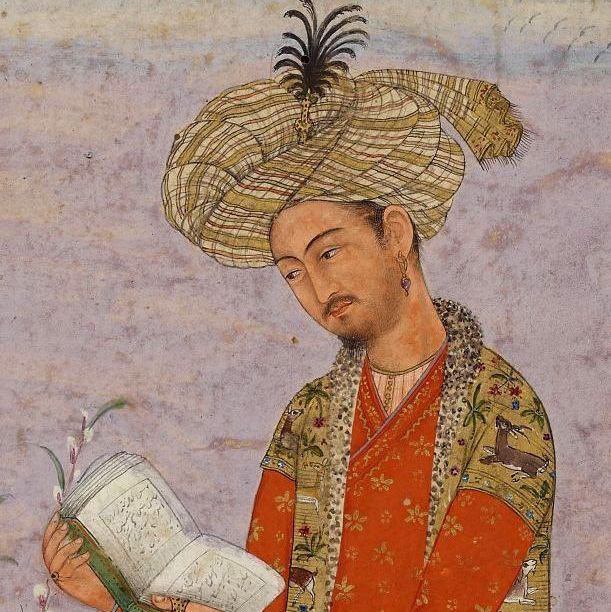

Zahir al-Din Muhammad, the 16th century Central Asian prince better known as Babur, is renowned for his fierce pedigree and proclivities. Descended from both Timur and Genghis Khan, he used military genius to overcome strife and exile, conquer northern India, and found the Moghul dynasty, which endured for over 300 years. He was a warlord who built towers of his enemies’ skulls on at least four occasions. Yet he was also a cultured man who wrote tomes on law and Sufi philosophy, collections of poetry, and a shockingly honest memoir, the Baburnama, in which he appears to us as one of the most complex and human figures of the early modern era.

Through the Baburnama, we learn that Babur was versed in courtly Persian speech and custom, yet nonetheless a populist who built strong ties with nomads and championed the vernacular Chagatai Turkic tongue in the arts. He was a pious man, but was also given to libertine escapades, including massive, wine-fueled parties.

But the first—and arguably one of the most culturally consequential—personal details he reveals is that he was a food snob. Babur loved the foods of his homeland and hated those he found when he had to reestablish himself in India, which to him was mostly a way station on the bloody road back to the melon patches of his youth. He didn’t just whinge about missing foods from home, though. He imported and glorified them in his new kingdom, laying the groundwork for his descendants to warp Indian cuisine so profoundly that they redefined that culinary tradition, as many know it worldwide, to this day.

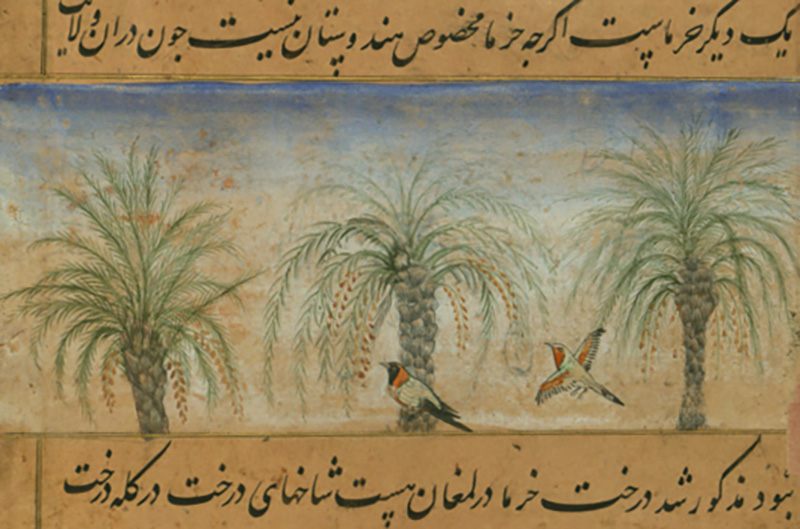

The Baburnama opens with a description of Ferghana, a region now split between Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan, where Babur grew up. Known then and now as the breadbasket of Central Asia, it follows that Babur would touch on agriculture. But in introducing his hometown of Andijan, Babur opens with a note on the quality of its grapes and melons before turning his attention to its layout and fortifications. He then ducks back to praise its game meats, especially its pheasants, which “are so fat, that the report goes that four persons may dine on the broth of one of them and not be able to finish it.” Only then does he tell us of the people who live there.

Almost anytime he describes a place back home, he starts with vittles. Margilan is known for its dried apricots, pitted and stuffed with almonds. Khojand’s pomegranates are proverbially good, but they pale next to Margilan’s. And Kandbadam is tiny and insignificant, but it grows the best almonds in the region, so it’s worth mentioning.

“Early sections of his Baburnama,” writes Fabrizio Foschini, in a report on Afghanistani melons authored in 2011, “really sound like a consumer guide to the fruit markets of Central Asia.”

Babur doesn’t forget food once he gets into the meaty war stories, either. He breaks one narrative to note that the area around a castle he just besieged grew a unique melon with puckered yellow skin, apple-like seeds, and pulp as thick as four fingers.

The Baburnama is not solely concerned with food. The bulk of it is a painstaking record of families and feuds, and Babur dwells on other seemingly random details that tickled him, such as a courtier’s talent at leapfrog. Since we don’t have a similarly honest accounting from his peers, it’s hard to say whether Babur’s epicureanism was atypical.

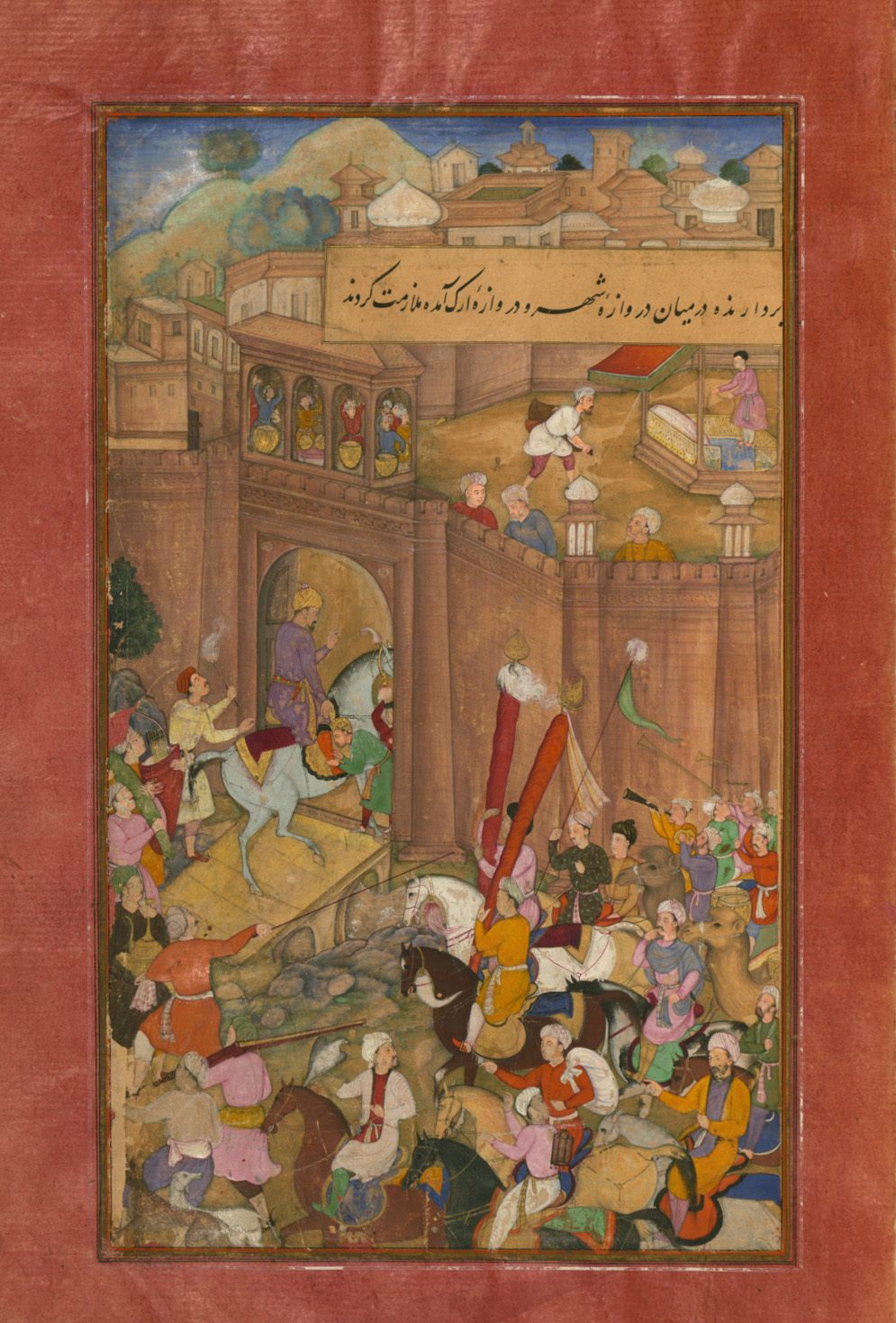

Given the chaos he grew up in, though, it’s incredible that Babur could spare any thought for food. Thrust to power at age 11 (by the Gregorian calendar), in 1494, he had to navigate bloody infighting amongst his relatives. Known as the Timurid princes after their conqueror-ancestor Timur, they jockeyed against each other for regional control. Babur became an active participant in this Central Asian game of thrones—he seemed particularly obsessed with taking the regional cultural capital of Samarkand. While he seized it in 1497, he lost the city almost immediately, as well as Ferghana, and (a very long story short) spent the rest of his teenage years reclaiming or losing bits of territory, fleeing into exile with remote nomadic tribes, and trying to court new followers and surge back. Although he never stopped trying to reclaim Samarkand and his homeland, by 1504, at age 21, he’d effectively been forced out of the region for the rest of his life.

That year, he pulled off a fantastic feat of warlord jiujitsu, flipping a rival’s forces into his service and marching on Kabul, which was vulnerable after undergoing its own contentious power shift. Babur took the city, and, naturally, set to cultivating its produce scene. In and around the city, he built at least 10 grand gardens that included a fair number of fruiting plants.

While Babur’s writings suggest a personal obsession with food, it’s hard to disentangle this obsession from homesickness. There were also political reasons for him to pay so much attention to cuisine: Food snobbery was a standard way for a Timurid prince such as Babur to make his mark and prove his elite bona fides in a new land. “The Timurids, while ethnically Turkic, based their legitimacy to a large extent on their being champions of Persianate ‘high’ culture,” says Central Asian historian Richard Foltz, “which included taste in food.”

Kabul proved ill endowed to support a successful campaign back to Ferghana, though. So Babur turned his attention to neighboring India. He got a lucky break when a new king—an inept man who clearly had dissenters and rebels in his ranks—came to power in the northern Sultanate of Delhi. Babur struck at this weakness, invading the region through the early 1520s. Despite being outmanned by a ratio of perhaps five-to-one in his final standoff with the sultan, he usurped the throne in 1526.

According to Foltz, Central Asians mostly looked down on Indians, who were neither Muslims nor Persianate. Babur, his recent biographer Stephen Dale notes, was also still deeply homesick. These factors, and possibly personal tastes, led him to dismiss his new territory, and especially its food: “Hindustan is a country that has few pleasures to recommend it. … [There is] no good flesh, no grapes or muskmelons, no good fruits, no ice or cold water, no good bread or food in their bazaars.”

Babur shouldn’t have had time for food in India either. He spent the last four years of his life fighting local insurgencies and consolidating his power. In 1530, he died at the age of 48, in Agra, the north Indian city where his great-great grandson Shah Jahan (lived 1592–1666) would later build the Taj Mahal. But he wrote letters in those years expressing his desire to return home, or at least taste its grapes and melons. He describes receiving a melon from Kabul and weeping as he ate it. He planted Central Asian grapes and melons in India, which brought him some joy. He even asked local chefs to make Persianate food for him, although one of them tried to poison him.

By establishing supply chains that brought his native agriculture and cuisine to the region, Babur left a lasting legacy. “He probably played a role in bringing Central Asian influences into the elite, courtly Indian life,” says Elizabeth Collingham, a food historian who explored Babur’s life and influence in her history of curries.

Granted, Babur was not the first Central Asian lord in what is now India. From 1206 to Babur’s day, five prior Central Asian dynasties ruled from Delhi. They too imported foods from home, cooked dishes they knew, and even did some fusion cooking. Trade and migration also meant there’d always been interplay between the regions, including culinary influence. Glimpses of this cultural mingling include the first mentions of samosas in the region’s written record—in accounts of those earlier medieval sultans’ feasts.

But according to Rukhsana Iftikhar, a historian of social life amongst the Mughals, the Persian word for “Mongols” by which Babur’s descendants came to be known, many of these dishes differed in style and flavor profile from the Persian-influenced Central Asian cuisine Babur preferred. They likely had not caught on with the general Indian population by the time Babur arrived, and few of them would sound familiar to fans of global Indian fare today.

Historians like Dale and Foltz chalk this up to the fact that previous dynasties—while they had some cultural influence—seemed to see India mostly as a piggy bank. They didn’t like to mix with local elites, and their culture was not grand or stable enough to invite mimicry and adaptation.

Babur, by contrast, was more statesman than raider. His pedigree and strong connections to Iran also gave him and his descendants more cultural cachet, and those descendants mixed more readily with the local populace. And for over a century after his death, Mughal rulers continued to praise the same foods Babur praised and keep the caravans of his beloved Central Asian fruits and nuts flowing. Babur’s successor Humayun brought Persian cooks to Delhi, and Humayun’s son, Akbar, was notably cosmopolitan and curious in the kitchen. Later descendents were not as invested in Persianate culture and the foods of Ferghana as Babur. But either as a means of displaying their wealth or of brandishing the superiority of their heritage, they carried on the culinary trajectory Babur set up.

Babur’s descendants also spent lavishly on their kitchens, elevating food as a status symbol. But unlike Babur, they made it a point to round up chefs from around their Indian domains, a practice that invited fusion. The grandeur and duration of their courts, argues Collingham, led local elites to copy their Persianate and Central Asian motifs and augment their own kitchens, leading to parallel fusion work in places like Hyderabad, Kashmir, and Lucknow. Over the centuries, these innovations coalesced into Mughlai food, a stable cuisine common across, although not ubiquitous in, northern India by the early 20th century.

This cuisine was defined by, among other things, aromatic, creamy curries, often incorporating the nuts and dried fruits Babur adored. It includes many dishes familiar to Western diners today: Korma, a blend of Central Asian nuts and dairy with Persian and Indian spices. Rogan Josh, a slow-cooked, Persian-style meat spiced up in the kitchens of Kashmir. And tandoori grilling, facilitated by Mughal tweaks to said grills and to marinades and spicing styles.

These dishes became ubiquitous in the West, Collingham says, because haute Indian chefs have long viewed Mughlai cooking the same way Western cooks used to see Le Cordon Bleu. Indians who set up restaurants abroad made Mughlai food the template of Indian food in the U.S. and U.K.—to the chagrin of Indians who grew up eating many other cuisines that remain hard to find outside their homelands.

None of this was a conscious project for Babur. But by setting up shop in Agra and Delhi, he created a wave that shook the foundations of India, culinary and otherwise. His tastes indirectly fueled 300-plus years of kitchen innovation. It’s no Central Asian dynasty of skulls and melons. It’s something more widespread and enduring, if unexpected or unwanted.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook