Exploring Chernobyl’s Imprint on Neighboring Belarus

The Polesie State Radioecological Reserve is close to Ukraine’s Exclusion Zone, but a world away.

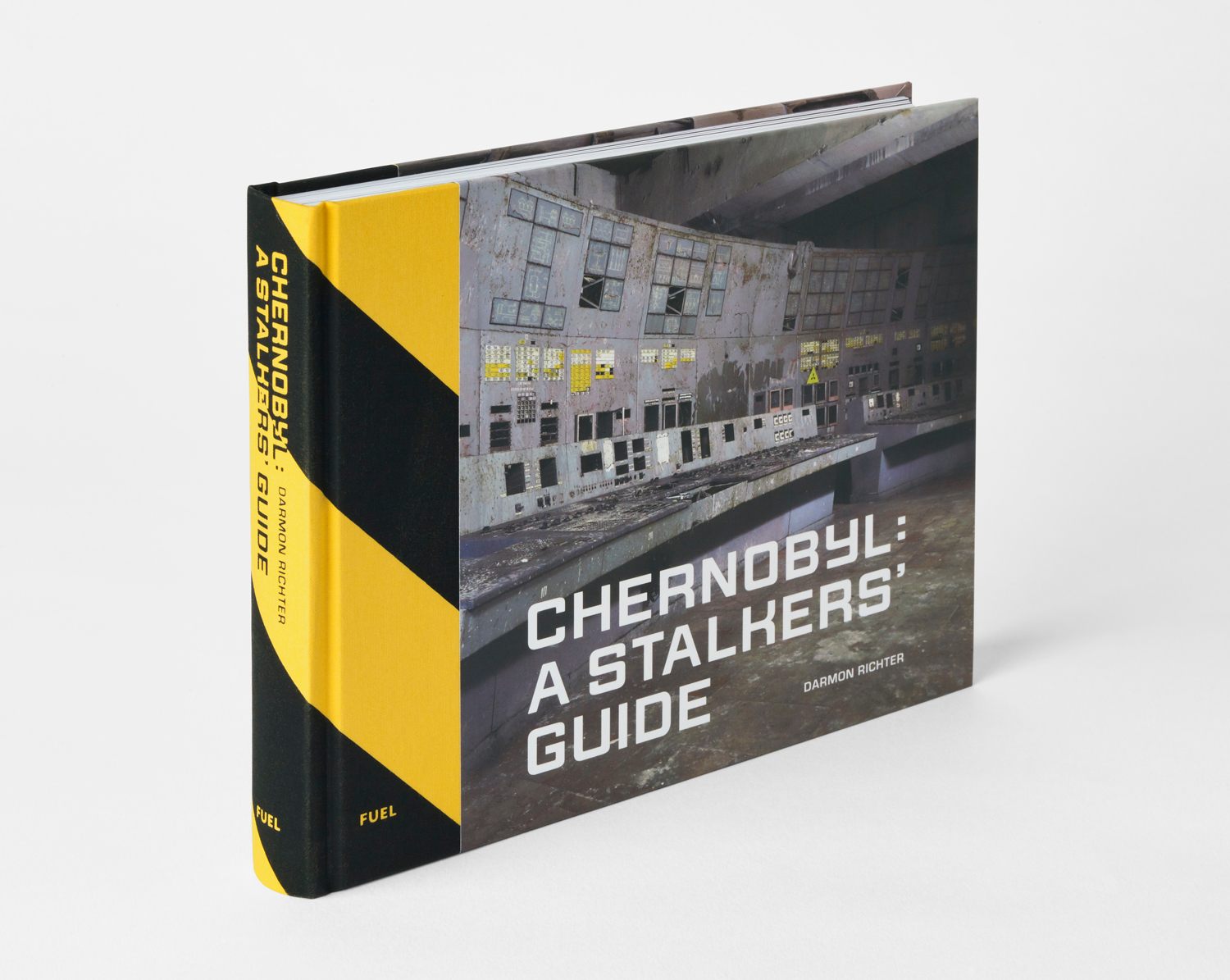

This story is excerpted and adapted from Darmon Richter’s new book, Chernobyl: A Stalkers’ Guide.

The Chernobyl disaster technically took place in the former Soviet republic of Ukraine, but radioactive contamination hardly respects geopolitical borders—especially the border with Belarus, a scant six miles from the site of the meltdown. Roughly two-thirds of the territory of Belarus suffered significant contamination, and within two years of the disaster, the Belarusian government had designated the most toxic area, along the Ukrainian border and closest to the plant, the Polesie State Radioecological Reserve. This restricted zone, once home to scores of villages, was to be used exclusively for scientific monitoring and research. In November 2018, as tourism to the Chernobyl area of Ukraine continued to grow, Belarusian authorities tentatively began offering tour routes through their Reserve. I’ve led some of these Exclusion Zone tours in Ukraine for years (Disclosure: including for Atlas Obscura), so the following summer I decided to pay Belarus’s Reserve a visit. The prescribed tours usually took the form of highly structured one-day itineraries focused on select locations, but I asked if it might be possible to explore further afield, on a two-day “monumenteering” trip. The Reserve’s administration approved my request.

I invite a few colleagues along, and we meet our guide, Karina, outside Minsk’s central train station—a pristine work of postmodernist design, all futuristic glass and steel, facing 1950s Stalinist towers still adorned with hammers and sickles. The city feels almost unnaturally clean. Even at this late hour, a team is polishing the station’s glass facade to a perfect finish. On the pavement out front, skater kids are wearing freshly ironed T-shirts.

Karina has only been to the Reserve 10 times herself. She is bright and energetic, a sharp contrast to many of the jaded veteran Ukrainian guides I know, whose Zone visits number in the hundreds or even thousands. Her independent tour company, Walk to Folk, specializes in adventure trips. For three years they have offered kayaking, hiking, camping, and cultural tours around Belarus. In December, a month after the Reserve was opened for tourism, Karina was invited on a promotional trip there, and soon after her company made it a regular tour offering.

We take the overnight train—seven hours in a sleeper carriage—to Rechitsa in Gomel Province. As stipulated by Belarusian law, our group will be accompanied throughout by scientists from the Reserve. Our scientist-guides are waiting for us at the station, both of them dressed in military-style camouflage gear. Dmitry is a botanist, around 50, with a kind face, eyes the color of Arctic glaciers, black hair, and a perfectly trimmed Freddie Mercury moustache. Leonid, our driver, is larger, with short, fair hair. He appears almost intimidating at first, until he smiles, and he suddenly looks more like a teddy bear. Karina doesn’t know either of them—she is assigned different scientists every time, she says.

Our tour is conducted in a classic UAZ-452 van, owned by the Polesie State Radioecological Reserve. The Reserve’s own vehicles are the only ones ordinarily allowed into the restricted area—these Soviet-built machines are not just best suited to the terrain, but are also the easiest to maintain and repair. Phone coverage is nonexistent in much of the Reserve, so each vehicle is fitted with a radio. Our small group huddles in the back, sitting on benches facing one another, as Leonid drives us across a vast, flat stretch of cornfield that was once given over to collectivized farming. Any houses we see are built to a uniform design, as though they were all produced during the same burst of construction. We pass a new solar farm, and Dmitry shouts something back that Karina translates: “Are you interested in monuments generally, or just monuments in the Reserve?”

“Generally,” I answer, keen also to avoid giving the impression that we are “disaster tourists,” interested in local culture only after it has been abandoned. Abruptly the van pulls over in the village of Malodusha, and Dmitry begins explaining a monument dedicated to local children who were killed in 1959 by a mine left over from World War II. “The echo of war,” reads a small sign marking this as a national historic site, and Dmitry explains how even inside the Reserve, the government still maintains every memorial.

The entrance to the Polesie State Radioecological Reserve looks similar to one of Ukraine’s smaller Zone checkpoints: no modern buildings, no police with guns, and certainly no souvenir van. While a sleepy-looking guard pushes open the gate, Karina reads us the rules for the Reserve, which essentially are the same as those of the Ukrainian Zone, including prohibitions on smoking, alcohol, and eating out in the open. Today is a busy day, with two tour groups inside the Reserve at once. As we listen to the rules, the other group pulls up in their own Soviet-era van, and their guide comes over to talk briefly with ours. He grins as he vigorously shakes hands with each of us. After he leaves, Karina says, “We call that guy Stalker Peter,” the term “stalker” used here to refer to those explorers with an almost obsessive interest in the Zone. His group are Belarusian ruin enthusiasts on a day-trip. “Some of them have gone to the Ukrainian side as many as 10 times. They’re real fans,” says Karina, though she explains that visitors to the Reserve are more often Polish and Czech. “For most Belarusians, the Zone is not so interesting. Many of us know someone who died or suffered from the disaster, so we already know as much as we want to. Besides, the place is hardly unique for us—there are plenty of villages in north Belarus where you can see abandoned buildings that look exactly the same as the ones here.”

The Polesie Reserve, established in 1988, now covers an area of more than 800 square miles and is divided into three regions: Brahin, Khoiniki, and Naroulia. Before the disaster, this largely agrarian region was home to more than 22,000 people spread across 95 villages, including numerous settlements of Old Believers, a schismatic Orthodox Christian sect. Now it’s home to moose, deer, lynx, and bison, as well as 48 of Belarus’s 189 species of endangered plants. No one officially lives in the Reserve, though 746 people work here, including 42 scientists divided into departments for, among other things, zoology, biology, and ornithology. Other Reserve employees work as border security, in forestry, or on fire-prevention teams.

After heading through the gate, we stop at monuments in the first few villages, most of them sites of wartime atrocities. The contrast with Ukraine is striking. Whereas Ukraine’s Soviet-era monuments have suffered greatly under the country’s decommunization law—either being removed altogether or allowed to fall into states of severe disrepair (particularly within the Zone)—here the monuments remain cherished focal points of local and national history. Even within the Reserve, surrounded by collapsing and ruined buildings, tumble-down pig sties, and overgrown roads, each village memorial we see is freshly painted. Many are also accompanied by a laminated sign bearing a title, some historical context, and a number relating to Belarus’s official list of heritage sites.

Dmitry, our quiet scientist-guide, is quite willing to tell us about every monument, but his real passion is for plants. On the outskirts of Babchin, beside a memorial to a massacre, he draws our attention to a succulent. “Russian houseleek—it’s extremely rare,” he says, lowering his voice as if to avoid disturbing the vegetation. “It only grows here, inside the Reserve.” Dmitry is from Brest, in western Belarus, on the border with Poland. He trained in forestry there, before taking a work placement at the Radioecological Reserve. After an initial apprenticeship he decided to stay on. While he has no personal connection to the disaster, or the lands most directly affected by it, this is an excellent opportunity for a career scientist, he explains. Dmitry enjoys his work in the Reserve. He loves the plants and seems to have a healthy respect for radiation: “This is the average in the Reserve,” he says, holding up the dosimeter for us to see the reading of 0.5 μSv/h, which is barely above the global average background radiation. “But later, I will show you some dirtier places.”

For the most part, the Reserve’s buildings are bare: tables, chairs, occasionally an abandoned boot or book, but none of the ghoulish decorations, such as the graffiti and arrangements of headless dolls and gas masks, that characterize tourism in the Ukrainian Zone. However, in Vygribnaya Sloboda we enter a deserted school to find toys propped upright on shelves, a scattering of gas masks, and books of fairy tales that have been left open beside maps and globes. I ask Karina who arranged them. She sighs: “One of the guides did it, the way they do in Ukraine. Many of the visitors have a code: They don’t want to touch things or move them around themselves, but they also want those photos—so this makes it possible. And when they share their photos online, more come.” She adds, without enthusiasm: “It’s good marketing.” Ukraine’s Chernobyl tourism industry is already committed to this type of sensationalism, but a more conflicted approach exists in Belarus. They want to use the Reserve for research and the sharing of knowledge, to preserve and respect its authenticity, but they recognize that dolls and gas masks are where the money is.

I ask Karina if the authorities want more tourists to visit. “Yes—but it seems we can’t agree on how to do this.” She explains how Reserve officials have stated that they don’t want more than 10 groups in any month. The approach of using their own vehicles and scientist-guides means they’re limited by the size of their staff and fleet. More than that, they don’t like the idea of the Reserve being “sullied” by over-tourism. As we leave the school, Dmitry draws our attention to a tree growing beside the building, with a modern plaque that details its genus and estimated age. “That’s a special one: Karelian birch,” says Karina. “Dmitry found it in April last year, and put up the sign in August.” Back on the road a little later, Leonid pulls over to marvel at a mushroom the size of a watermelon.

We eat a lunch of pickles, sandwiches, cured meat, and boiled eggs on a foldout table that only just fits in the back of the van. Karina talks about the evacuation in 1986: “They made a mistake evacuating villagers to the city,” she says. “These people had lived their whole life in the village, working at the collective farm, and then they were relocated to flats. They were called ‘Chernobyl houses’—around Malinauka district on the east of Minsk. A lot of those people died young. Many became depressed and started to drink. They couldn’t find work and just couldn’t deal with the city. So the second wave of people who were resettled, from the edges of the Reserve where it wasn’t so urgent, were given houses in other villages instead. The government learned from their mistake.”

After lunch we visit Zherdnoye, one long village street lined on both sides with decrepit wooden houses. Hidden among the foliage, beams carry hand-carved details, loving touches of individual artistry now lost to the forest. All around the village are fields of corn. “Are they growing food?” I ask.

“For the cows,” says Karina. But who eats the cows? I wonder.

I discover that much of the Reserve has been converted back into farmland. Aside from corn and cattle, we drive past fields of freshly mown grass used to make hay for the horses that are bred here, which are then sold for riding and farm work. “We have Przewalski’s horses, too,” Dmitry says proudly, referring to an endangered wild equine. “They were originally released in Ukraine, but they’ve started crossing the border, to come and live in our Reserve.” I cannot bring myself to tell him that in Ukraine I’ve met poachers who boast about turning them into sausages, but I do wonder if perhaps the horses feel safer on this side of the border. By the roadside, we pass huge quantities of massive logs stacked for collection. Much of this lumber goes to Lithuania, a country with a booming manufacturing sector, including the large-scale production of IKEA furniture.

On the drive back out we pass a village sign that reads “Prosmychi.” Nearby an old man leans on his rake to watch us. The beautifully maintained village houses are painted in a striking palette of purples, oranges, and navy blues. Tidy stacks of black plastic–wrapped silage bales stud the field behind the houses. In the distance, smoke rises dirty-yellow from a crop fire. Planted in the bushes at the road’s edge is a solitary radiation warning sign—the only acknowledgement that this village is in any way unusual. We haven’t passed radiation control yet and there has been no indication that we’ve even left the Reserve. I ask if we’re still inside it. “No, we left a while ago,” says Karina, “but now we need to drive back to the entrance for a radiation check.”

The Belarusian Radioecological Reserve’s lack of a solid border marks a striking difference from the situation in the Ukrainian Exclusion Zone, where police with Kalashnikovs watch over checkpoints. It would be easy for anyone to ignore the warning signs and just walk straight in. “So why don’t they?” I ask. Karina explains that the penalties are severe for anyone caught trespassing in the Reserve. However, once a year, on the weekend after Easter, the citizens of Belarus are given free rein to drive their own vehicles into the Zone and visit their former homes and the graves of loved ones. Children can go, too, and while all visitors are expected to carry identification, they are not required to pass through radiation control. “Ukraine has the same thing,” says Karina. I ask what stops these people from stealing metal, or entering the more contaminated areas closest to the border and the power plant beyond , which, even on this special day, remain strictly off-limits. “Because they know it’s bad to be caught.” Then as if reading my mind, she adds, “The penalty is even worse for foreigners.”

Looping through the town of Bragin, back toward the entrance to the Reserve, by 4:30 p.m. we’re pulling up beside the checkpoint we passed through this morning. Leonid toots his horn and a gray-haired man in camouflage makes his way slowly over from the security hut. He carries a full-size radiation detector, and one by one he waves the wand across our boots. We’re all clean and Dmitry, grinning, tells us we’ve likely received a total dose of around 1.5 μSv. “One day in the Reserve, the equivalent of half an hour in a plane,” he says.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook