The Unfortunately Action-Packed Afterlife of a California Grave-Robbery Victim

Nearly 140 years after being snatched, almost dissected, and eventually reburied, Clara Loeper may finally get a headstone.

Dennis Evanosky is deep in the underbrush, holding out his arms for balance as he makes his way across the uneven terrain around the perimeter of the massive Mountain View Cemetery in Oakland, California. He’s looking for a grave, the final resting place of a woman whose afterlife has been startlingly action-packed.

It’s February 2021, and Evanosky and I are searching for Clara Loeper, a 21-year-old whose corpse was snatched from this cemetery in 1883. Her cadaver was returned to its grave after turning up on the slab of a medical college dissection room—but where was it now? Like many graves in this old burial ground, it’s been lost to time and the initial failure to provide a tombstone. “It’s important to mark the graves that are unmarked,” says Evanosky, a local historian, author, and Mountain View docent. “It’s a respect thing for me to rediscover these people and let others know where they are.”

The recent search to unearth the history of Loeper’s burial began—as many quests to unspool local mysteries do—on Facebook. Throughout much of 2020, photographer Mike Ahmadi posted images scanned from glass plate negatives found in his neighbor Howard’s barn. He’d upload photographs daily, paired with prompts like, “Well, here is one for you super sleuths to figure out.” Armchair historians who visited the “In Howard’s Barn” page enjoyed helping him identify the people and places in the pictures.

One photograph seemed to show a medical school dissection, with nearly 20 students crowded around two corpses. One commenter mentioned Clara Loeper and her unfortunate ties to the Eclectic Medical College, wondering whether this might be a photograph of the school. Intrigued, I started tracing Clara’s story through old newspaper accounts. She was born with a marked spinal curvature and partial paralysis of her limbs, and was unable to walk or talk. Her mother, Wilhemina Loeper, spoon-fed her. Seven weeks before Clara’s death on April 3, 1883, Dr. Rudolph of the Eclectic Medical College came to visit.

Believing Clara would soon die, Dr. Rudolph asked Wilhemina to donate her daughter’s body so that doctors could learn more about her condition. Mrs. Loeper was unwilling to send Clara’s body to the college, but agreed to a future autopsy at home. This wasn’t what Dr. Rudolph hoped to hear. The next day, he ran into Mrs. Loeper on the street, repeated the request, and was again refused.

At Clara’s April 5 burial, her mother felt unsettled and shared suspicions that Dr. Rudolph might try something uncouth, so someone slipped a piece of wire into the mound of dirt covering the grave. On the 6th, Mrs. Loeper returned “and perceived at once that the grave had been violated,” the Oakland Tribune reported in 1883. Dirt was scattered, and the wire was nowhere to be seen. Mrs. Loeper alerted the cemetery superintendent, who started digging and confirmed the wretched truth: The coffin lid had been axed open, and Clara was missing.

She had been taken away nude. “Clothes were rudely torn off and thrown pell-mell into the grave. Even the stockings were pulled off,” noted the Tribune article. It’s hard to say why the thieves left Clara’s garments behind; maybe they thought the clothes would be easy identifiers, or perhaps they were concerned about adding property theft onto the crime of body theft. Grave-robbing was a felony in California, and a conviction could lead to a five-year prison sentence.

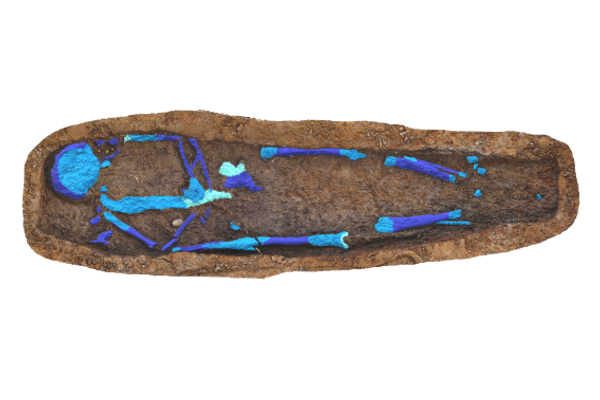

On April 7, armed with a search warrant, a sergeant and five officers descended on Eclectic Medical College, where two professors claimed the dissecting room was empty and refused to let them in. Officers picked the locks—and inside, they found Clara on a table. She had not been dissected, but her head had been shaved. The officers removed her to the coroner’s office.

The Tribune reporter went to the cemetery the next day and found tracks from the grave-robbers’ wagon, which had awaited its cargo on the other side of a low fence. The reporter gained permission from the coroner to look at Clara’s body, and concluded that she was probably pulled from her coffin by a rope wrapped around her neck and mouth. Clara was reinterred, with an armed guard posted to remain until enough time had passed to render the body unusable for science.

Like many other 19th-century medical training grounds, the Eclectic Medical College was notorious for grave robbing. A chain of about a dozen homeopathic schools, its Ohio headquarters was the site of an 1839 uprising after multiple lawsuits had done nothing to curb the grave-robbing habit. In what came to be known as the Resurrection Riot, a mob armed with firearms swarmed the college, enraged by several disturbed graves, including one that housed a woman who died in an asylum and was buried in a potter’s field before relatives could claim her. Sure enough, her body was found on the dissecting table.

Although police had seized several shovels with moist, caked dirt, and a box that may have carried Clara to the college, they didn’t make any arrests in the Loeper case. Mrs. Loeper hired her own detective, and on the 12th, Doctors Crowley and Harrison were arrested for the felony charge of grave-robbing, along with a janitor.

Mrs. Loeper took the stand at the police court trial, as did a “rather agitated” Dr. Crowley. One physician testified that Dr. Crowley couldn’t possibly have taken part in the theft, since he had been receiving opiates in his bedroom at the time. Multiple witnesses denied seeing Clara in the dissecting room. Meanwhile, onlookers indulged their curiosity for the macabre: While the court took recess, the Oakland Tribune noted that spectators inspected the coffin for signs of Clara’s “stains” and showed morbid interest in the splintered box. The court ultimately discharged the defendants, while Mrs. Loeper wandered the courtroom weeping, “It’s too bad, too bad, too bad. They stole my child, they stole my child.”

College representatives were never made to say how they ordinarily obtained bodies for dissection, but one source was the County Infirmary. When the County Board of Supervisors mounted an investigation of terrible conditions at the infirmary that October, Dr. Crowley fumbled into a discussion of taking unclaimed bodies for the college’s dissections. Pressed to say how many, he sputtered, “We received six or seven, or eight, bodies… no more than eight; did not receive more than fifteen, or twelve,” the Tribune reported. One can practically hear sweat rolling down his hairline. The implication was that infirmary patients were treated so badly that they expired—and then their bodies could be dissected at the college.

Meanwhile, Mrs. Loeper continued to be tortured about whether Clara rested in peace. After the reburial, a silk-hatted man came to Mrs. Loeper’s house offering $100 for the body. This was a lot of money—since the family was poor, Clara shared a grave with her father, one coffin atop the other—but Mrs. Loeper refused. Her son proposed putting an “electric bomb” in the grave to deter repeat looters, and the San Francisco Examiner reported that the mother “is fretting herself to death for fear of a repetition of the outrageous crime.”

Mrs. Loeper returned that May to check on Clara. The kindly superintendent started shoveling, and Mrs. Loeper was relieved to find that Clara was there in an advanced stage of decomposition—no longer stealable.

The school faced still more scandal in March 1884. A little boy had died after being attended by Dr. Crowley, and the Alameda doctor who filled out the death certificate listed “eclecticism” as the cause of death. Dr. Crowley asked that doctor to retract the certificate. (And when he refused, Dr. Crowley punched him in the face multiple times until another doctor intervened.) The last of the Eclectic schools closed in 1939.

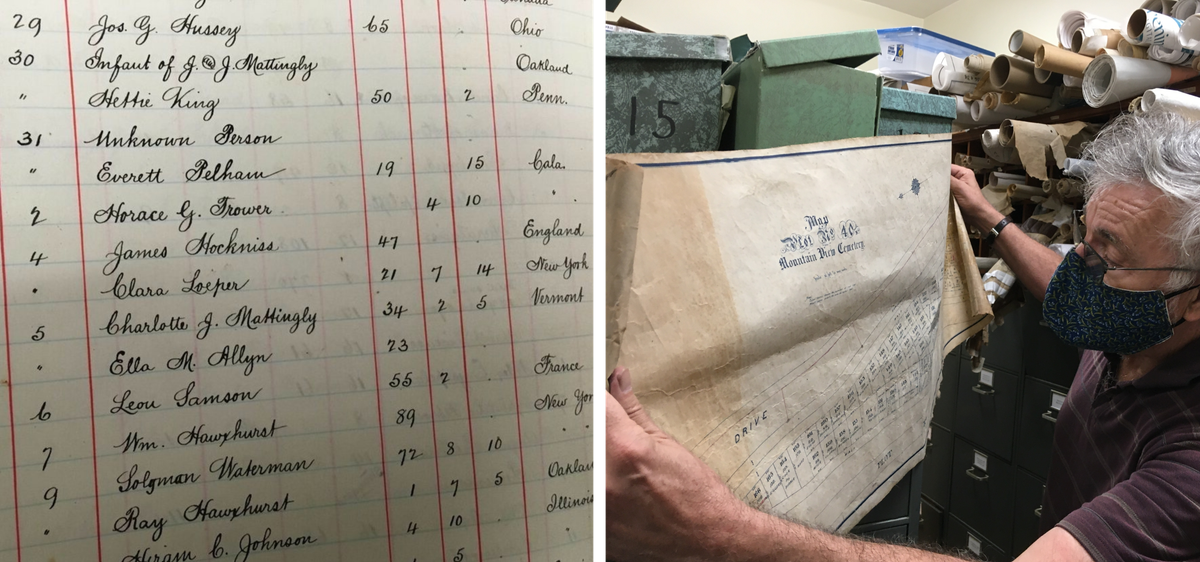

After hearing Clara’s story in October 2020, Evanosky offered to help find her. In the cemetery office, we looked her up in a handwritten volume—The Index of the Dead—and found her on the threadbare map so delicate it cannot be unrolled many more times before disintegrating. We set out on foot.

We were unsuccessful during that outing, but Evanosky later found her on his own. It took a few months for me to return to Oakland to pay my respects. Evanosky had defined the grave’s rectangle with eucalyptus leaves. As I stared down at Clara’s shared plot of earth, I thought about how, to the men who stole her body, she was more an object of fascination than a person whose life mattered.

Someday, her resting place may be more formally marked. In the cemetery’s maintenance yard lie stacks of unused tombstones. Some were incorrectly carved, and others landed there because the deceased’s family never paid for the work. Evanosky is petitioning for one to be used for Clara and her father. Placed flat on the ground, the “used” side will be hidden, and Clara will get a bit of kindness over a century later. That’s already happening: Evanosky noticed that after her gravesite was made apparent, passersby left stones behind to show that they had visited.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook