When New Yorkers Were Menaced by Banana Peels

They slipped and fell. Really!

In 1907, Anna H. Sturla boarded a ferry, slipped on a banana peel, and demanded $250 in compensation from the boat’s operators. Three doctors had examined her, she claimed, and told her she needed an operation. She received $150—a significant sum at the time, although less than the $500 she received after her first banana-peel incident, a fall on the train-station steps at 125th Street and Park Avenue.

“Not six months went by after that,” a New York Times reporter wrote, “before Mrs. Sturla was once more in trouble with these arch-foes of hers, banana peels.” In total, Anna Sturla received $2,950 from 17 accidents in four years. In 11 cases, Sturla blamed banana peels. When the Times wrote about her, Sturla was on trial for making fraudulent complaints.

But for years, she was taken seriously. After all, many New Yorkers suffered similar injuries. Slipping on a banana peel is a cliché, a vintage vaudeville gag. But its origins weren’t just slapstick comedy. Before it became a comedy trope, banana peels menaced New Yorkers for decades.

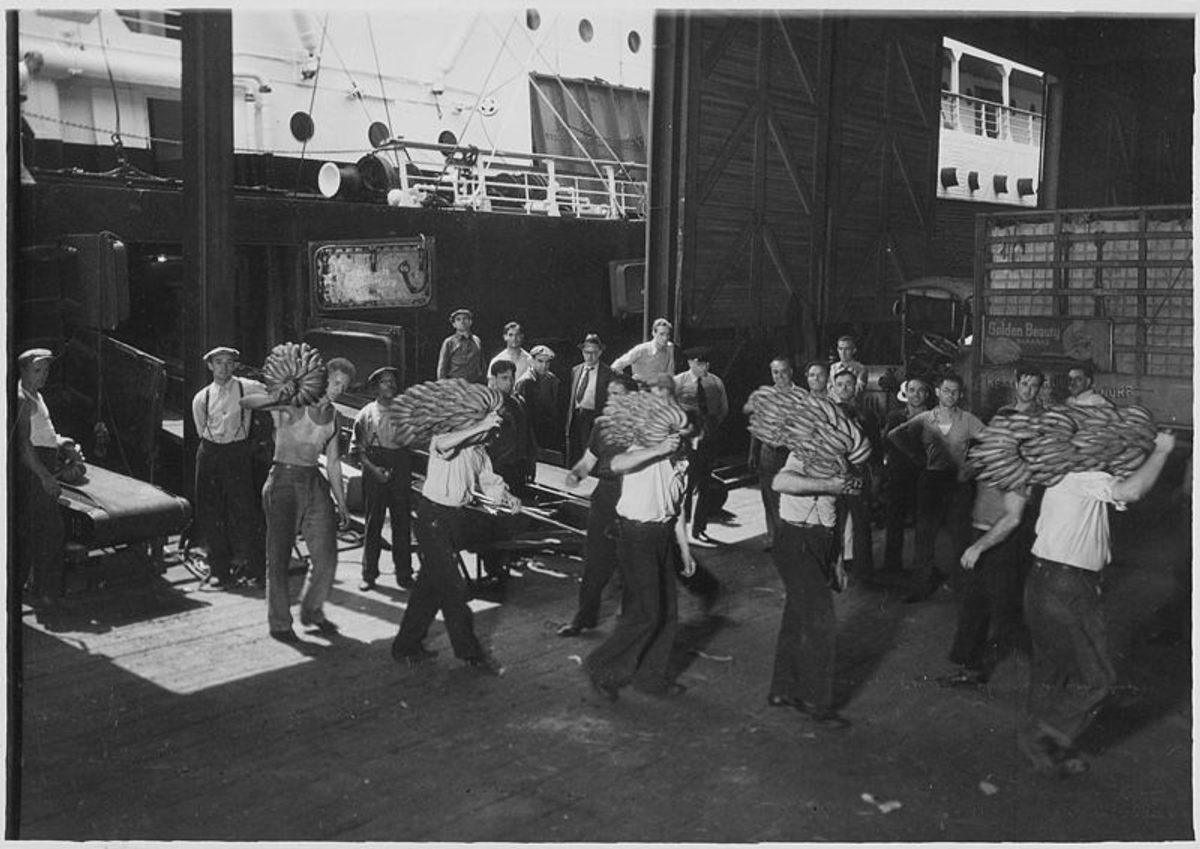

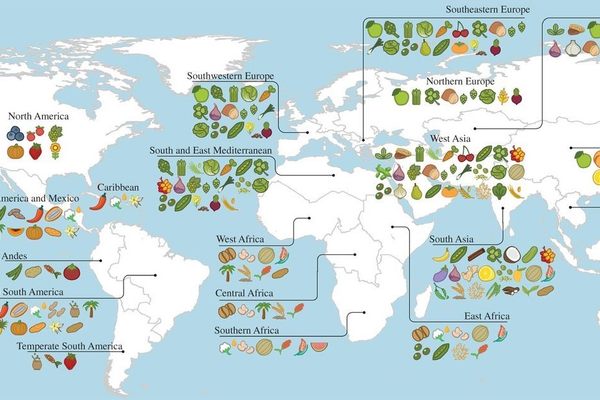

When bananas first arrived in New York City, it was a triumph of logistics and planning. After the Civil War, writes Dan Koeppel in Banana: The Fate of the Fruit That Changed the World, bananas in the U.S. were like caviar: expensive and hard-to-find status symbols. After all, sailing the tropical fruit from the nearest banana-producing area, Jamaica, could take three weeks by schooner, which was longer than the banana’s shelf life. But once an entrepreneur realized that leaving bananas on-deck kept them cool and unspoiled, it sparked a banana bonanza. Soon, networks of factories were providing ice to cool bananas in transit, and the fruit became a ubiquitous and cheap snack stateside.

But it came at a cost. Vendors touted banana skins as “sanitary wrappers” and sold them as a street food. Sure enough, New Yorkers discarded the wrappers onto the street, and the pages of turn-of-the-century New York City newspapers contained accounts of shockingly serious banana-related injuries.

“A wealthy merchant, aged 75 … slipped on a banana peel in front of his home and broke his right leg near the hip,” the Times reported in 1884. “He is not expected to recover.” More than 30 years later, an article headlined “Banana Peel Causes Death” described how a factory worker slipped and fell into the street, where a truck hit him.

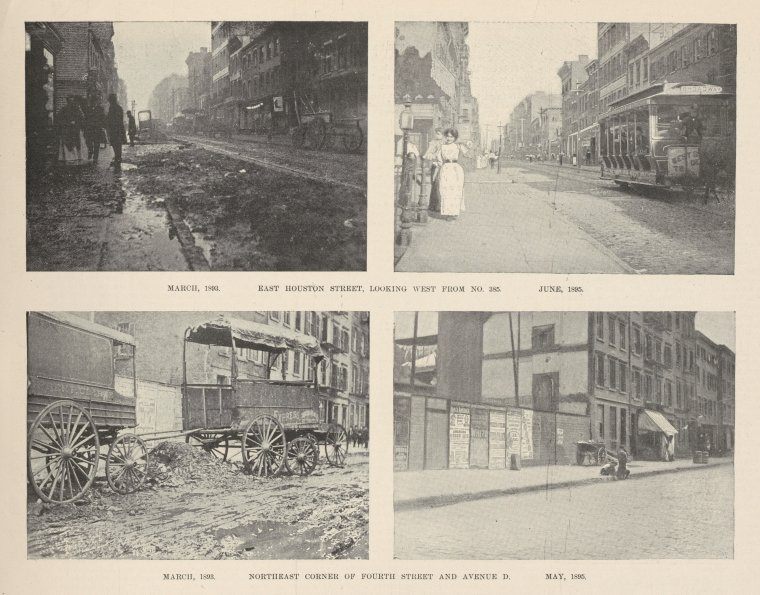

A lone banana peel on a sidewalk—its yellow color practically a hazard sign—doesn’t seem very threatening. But in the late-19th century, trash in New York City piled up ankle- or knee-deep. The city did have a Department of Street Cleaning, created in 1881. But this was the era of corrupt, Tammany-Hall politics, and jobs were handed out on the basis of party loyalty, often to absentee workers who misused funds.

Accounts and photos from the time are stunning. New Yorkers threw their trash in the street, where no one picked it up, leading the city to release wild pigs to eat the refuse. Dead animals lingered in gutters for days. In this environment, discarded banana peels rotted into slippery messes and mottled into a camouflaging brown.

Orange peels and potato skins caused slips and falls too, but pedestrians feared bananas, which scientists have since confirmed rank among the slipperiest of fruits. Letters to the editor demanded harsh penalties for discarding peels. Theodore Roosevelt, then New York City’s chief of police, declared war on banana peels, and gave a public address to his captains and sergeants on “the bad habits of the banana skin, dwelling particularly on its tendency to toss people into the air and bring them down with terrific force on the hard pavement.”

New Yorkers were not alone in fearing bananas. St. Louis took up the issue and banned the public disposal of peels, and accounts of death by discarded banana came even from Panama, a country intimately familiar with the fruit. But the scale was entirely different in New York City.

In other American cities, the garbage men did their jobs and cleared trash and banana peels from the streets. Yet according to Robin Nagle, anthropologist-in-residence for New York City’s Department of Sanitation, in an interview with Collectors Weekly, “New York persisted in being infamously, disgustingly dirty.” It’s likely this confluence—New York City’s corruption, and its status as an entertainment capital—that led to movie stars and comics performing so many banana-peel gags. A weary Charlie Chaplin griped the only way to get a laugh was to have a character step over a banana peel and directly into a manhole.

In the 1890s, a police corruption scandal—incited by a minister who hired a private detective to show him the city’s illegal brothels, bars, and gambling venues, as well as the policemen enjoying them—exposed Tammany Hall corruption and swept a reformist mayor into office. The new mayor, in turn, appointed the man who would rescue New Yorkers from banana peels: George Waring.

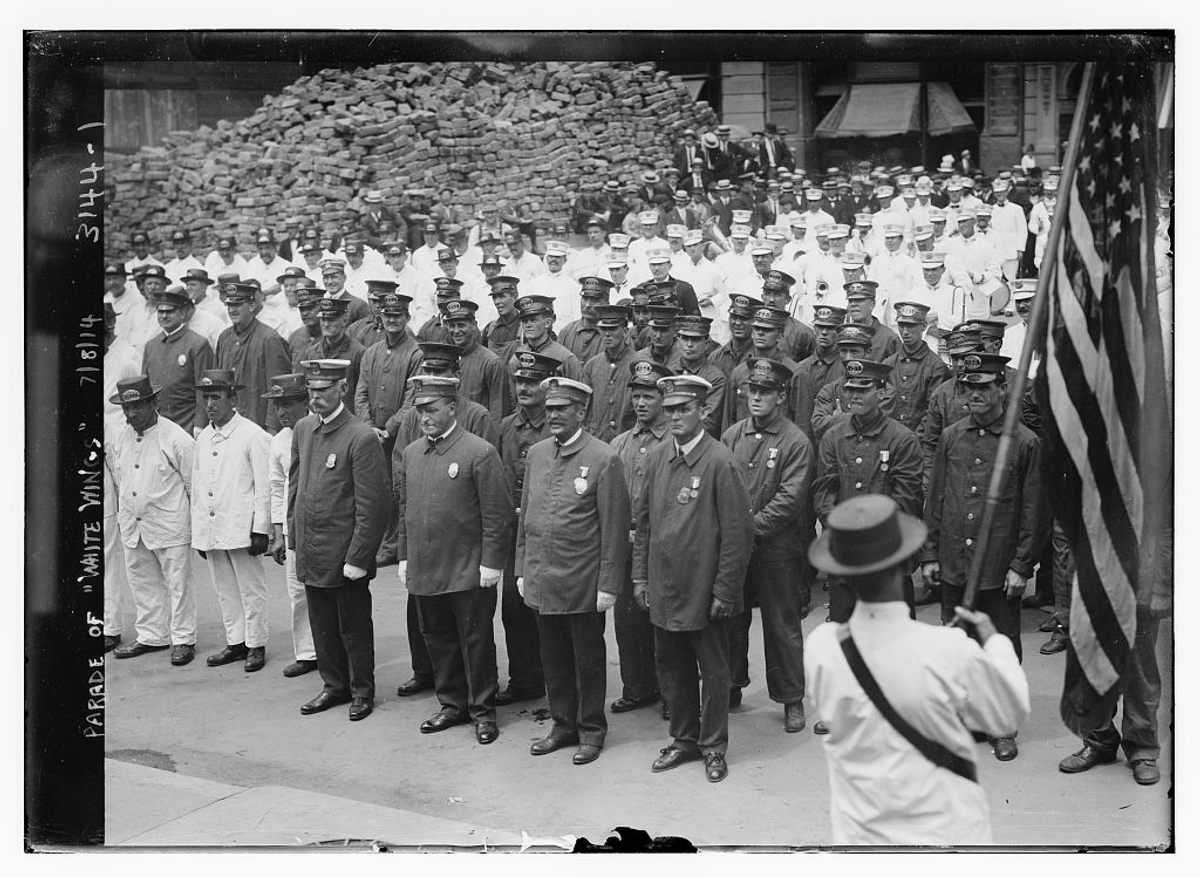

Waring was a Civil-War colonel whose re-design of sewers in Memphis, Tennessee, ended an era of local epidemics. As commissioner of street cleaning, he rooted out corruption and instilled military discipline. “He found the street-cleaning force a rabble and left it an army,” the Times wrote. He insisted his men wear white uniforms—to the dismay of their wives—in order to associate them with health, ordered them to march down the streets, and prioritized cleaning poor neighborhoods.

They were not met with open arms. “In the really poor corners of the city, like Five Points, to see anyone from the local government come into the neighborhood was not good news for local residents,” Nagle explained. “They threw bricks at the street cleaners and came out to fight them with sticks.” But Waring sent them out again, and eventually, they won hearts and minds in the tenements by transforming New York’s streets. Soon enough, the trashmen had pride of place in city parades, and the mayor gave them “manly and helpful talk[s]” on the importance of their work. A corrupt department that once pocketed taxpayer money had become an exemplar of government service.

As trash and peels disappeared from city streets, banana slips lived on only in films and slapstick comedy. Now, decades later, people are puzzled by banana-peel gags, and question whether it’s even possible to slip on one. Our puzzlement, though, is a testament to the success of people such as Waring and his men, who cleaned the streets of New York and saved us from the scourge of banana peels.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook