The Strange Case of Mexico’s Shrinking Jumbo Squid

Too many El Niños have diminished the “diablo rojo.”

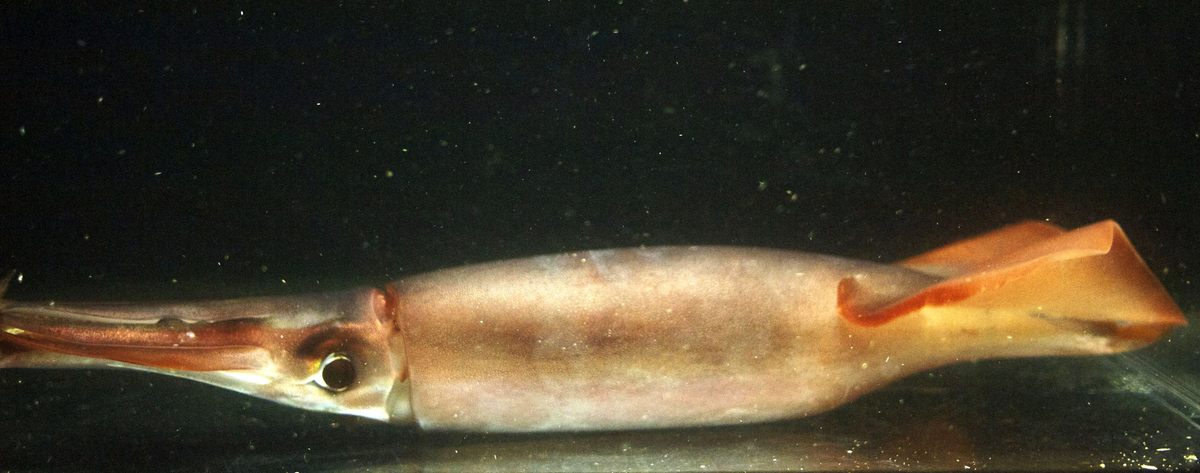

At the turn of the 21st century, Mexico’s Gulf of California was ruled by human-sized cannibal squid. The Humboldt squid weren’t quite giant but they certainly were jumbo, growing up to six feet long and weighing up to 100 pounds. They mobbed those tropical waters, devouring fish, crustaceans, and cephalopods—including other Humboldt squid. Their reign was chaotic underwater and lucrative on land, as they nourished the world’s largest invertebrate fishery. At dusk, you could see them swarm, thousands of tentacle tips breaking the surface and grasping at air, remembers William Gilly, a marine biologist at Stanford University’s Hopkins Marine Station, whose professional academic headshot is a photo of him cradling a hefty Humboldt like a Madonna with child.

But by 2015, these large marine predators vanished—or rather, they shrank. Squid fishers who had become accustomed to hauling up catches longer than themselves found creatures barely fit for calamari. They were still Humboldt squids, but shrinky-dink versions. “You could catch 20 or 30 of them and not fill up a bucket,” says Tim Frawley, a Stanford research fellow and the lead author of a new study in ICES Journal of Marine Science that finally solves the mystery of Mexico’s missing jumbo squid.

Frawley had been working as a commercial fisherman in Alaska and Maine before he fell in love with the thriving squid fishery in the Gulf of California. He saw local fishers lug in mammoth squid, hand over hand, and was hooked. Humboldt squid only surface at twilight, a few hours after dusk, when the light has almost disappeared from the sky. The squid change color, flashing from pale pink to red in syncopated patterns as fast as four times per second. In Mexico, these demonic flashes earned them the nickname diablo rojo. In deep water, the red coloration causes the squid to seemingly disappear, and Frawley remembers watching fishers haul in squid that seemed to blink in and out of existence while hooked on the line. “It was a sight to behold,” he says. “I was all in.”

Frawley joined Gilly’s Stanford lab in 2013 and crafted a PhD project oriented around tagging the squid to build 3D models of their habitat. But as soon as he made it down to Baja, the big squid seemed to have disappeared. Fishers only found those tiny Humboldts, so small you could hold one with just one hand. So Frawley needed a new project, and there was one obvious place to start. He needed to figure out what happened to all those squid.

Luckily, the once-thriving jumbo squid industry had left behind a healthy record of squid size over the prior decade, with the measurements of more than 1,000 individual squid. Frawley dug into the data and compared the squid size timeline with other data, including satellite photos, temperature and salinity readings, shifts in fishery productivity, and observed changes in ocean habitat. The research was far less exciting than hooking these monsters, but also considerably less slimy.

Frawley and the other researchers found a flurry of factors that drove the jumbo squid’s demise. The Gulf of California historically cycled between warm-water El Niño conditions and cool-water La Niña phases. The warm El Niño waters were inhospitable to jumbo squid—more specifically to the squid’s prey—but subsequent La Niñas would allow squid populations to recover. But recent years have seen a drought of La Niñas, resulting in increasingly and more consistently warm waters. Frawley calls it an “oceanographic drought,” and says that conditions like these will become more and more common with climate change. “But saying this specific instance is climate change is more than we can claim in the scope of our work,” he adds. “I’m not willing to make that connection absolutely.”

To cope with warmer waters, the squid have begun reproducing at an incredibly young age. Jumbo squid normally reproduce after 18 months. Now they’re breeding after just five or six months. “The squid says there’s not going to be much food leftover later, so I’m going to reproduce now before there’s no food,” Frawley says. “But how the squid makes this decision I don’t know.”

This ability to shrink is a handy evolutionary strategy that makes squids a unique sentinel of environmental change. But it’s also alarming, and happening worldwide. “This is the equivalent of a bear becoming reproductive as a little cub,” Gilly says. Recently, he’s seen other squid that normally become sexually active when they are around the size of a banana begin to reproduce at half that size. Until water conditions cool down in Mexico, Gilly says, the jumbo squid in the Gulf of California will be anticlimactically small.

It was never easy to catch a jumbo squid when they were actually jumbo. There’s really only one method: Send a weighted, luminescent jig down around 300 feet and then sort of wiggle it around. It’s called jigging, and it sounds simple enough. But when the squid you seek weighs up to 100 pounds, you need a strong line and strong arms to get the beastie on board. “I got yelled at by the guys my first time down there for letting a squid dominate me,” Frawley says, bashful. “It’s like riding a horse. You can’t let the squid take control.” Squid fishers must be constant and forceful, at least until the animal goes slack.

But for the past five years, the equipment the squid fishers use has become comically oversized for the task. “Normally, they use hand lines that can hold 400 pounds, like weed-whacker lines, and big lures that weigh a pound,” Gilly says. “But these lures are so much larger than the squid now.” Now, fishers are resorting to trout rods with line that can handle 10 pounds. It works just fine, but it takes the same amount of time to catch a tiny squid as it did to catch a jumbo one. Frawley says small-scale fishers in Baja have begun to diversify what they catch in order to stay afloat.

While consulting with these fishers for his research, Frawley began to understand that the entire ecosystem of the Gulf of California has begun to shift. With no more jumbo squid, sperm whales that used to feed on them have moved on. So, too, have the sardines, confronted with waters lacking in the nutrients to support their schools.

Gilly expects that the Gulf of California will continue to change in ways nobody will be able to predict. “If you alter a complex system like the Gulf of California for a long enough time, new species will take over and new rules will take over, “ he says. “If you’re a booby and you like eating small squid, you might think this is great.” If you’re a jumbo squid that believes in its name, not so much.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook