The Competitive Book Sorters Who Spread Knowledge Around New York

Inside an annual contest of brains, brawn, and library logistics.

The Lyngsoe Systems Compact Cross Belt Sorter hogs most of a drab, boxy basement under an unremarkable office building in Queens—238 feet of fast-flying conveyor belt, like a cross between a baggage carousel and a racetrack. The machine scans the barcodes on thousands of library books an hour, and shoves them quickly, efficiently into bins so they can make their way between branches of the New York and Brooklyn Public Libraries. Requested books are dropped off here every day by the truckload and, once processed, are promptly shuffled off to eager readers all over the city. A day’s work is typically about 40,000 requests, and each one of those books needs to be placed—by hand—onto an empty space on the relentless sorter, with the barcode facing the right way. But November 9, 2018, is no ordinary day. For the sixth time, an elite squad of 12 professional New York sorters—the fleet-fingered men and women who feed books into the machine—will compete with their counterparts from Washington State’s King County Library System to see who can process the most books in an hour. Losing to King County, which serves the Seattle suburbs and was the first library in the United States to get a Lyngsoe sorter, is not an option.

Enter Sal Magaddino, Deputy Director of Logistics for BookOps, the collaboration between the New York and Brooklyn Public Libraries that operates this facility. Formerly the NYPD captain in charge of Brooklyn’s major crimes investigations, Magaddino glides around the machine, with one hand gesturing to its component parts and the other clutching a styrofoam cup of coffee. Wearing a checked suit, he gloats in consummate Brooklynese about the remarkable operation this beast enables. Sorting items that move every day from the tip of the Bronx to the lip of Staten Island, his team tallied nearly 7.5 million successful deliveries last year. It seems like an odd gig for a former major crimes investigator, but to him it brings to mind the challenges of the 2000 World Series, when the Yankees played the Mets and Magaddino helped secure the airspace for the NYPD. “You have to have a logistic component” when dealing with homicides and robberies, he says. You have to know “how to use resources.” It is the same here, and the whirring giant in the room is only one of his resources; another is the team being put to the test today. A perfect score for them—not a book slot missed—would be an astonishing 12,800, the most the machine can handle in an hour. And that’s his goal. A perfect game in the World Series.

That number may be virtually unachievable, but there was a time not so long ago when it was beyond imagination. Before the Lyngsoe was introduced in 2010, library logistics were “a dismal failure,” says Magaddino. The sorters couldn’t crack 12,000 on their best full day, though it was no fault of their own. The process for sorting book requests consisted of dumping crates of books out onto a giant table, rummaging through them, and dealing with each book individually. First, they had to examine the slip rubber banded to each book, and then walk it over to the assigned point of departure for its destination.

“We weren’t able to keep up,” says George Rodriguez, who has been sorting for the New York Public Library (NYPL) for 17 years. Getting books out to patrons used to take up to six weeks, “if they ever got it at all,” says Magaddino. Tens of thousands of books in the red, he insisted on making a major change as the new BookOps building was being designed. Washington’s busy King County Library System (not to be confused with Brooklyn’s Kings County) was a guiding light, having had great success with a Lyngsoe sorting machine, so Magaddino fought for the $2 million needed to bring one to New York. Once it was finally installed, the backlog disappeared. But there was still unfinished business: Could BookOps now best its northwestern nemesis, King County, which had heralded the dawn of this book-delivery golden age? So the battle of high-speed logistics and library pride was set. Each library would get an hour to sort as many books as they could with the Lyngsoe—King County on their machine in Preston, Washington, and BookOps on this one. Five annual competitions have come and gone, and so far, the Pacific Northwest is up 3–2. Last year, technical difficulties led to a cancellation of the contest. So this is the long-awaited Game 6, and BookOps wants to make a statement.

With minutes to go until game time, the 12 elite sorters have emerged, wearing matching BookOps T-shirts. They march toward the machine as if boarding Apollo 11. The offices upstairs have emptied into the basement, and a wide variety of library personnel fill every available space in the room to cheer the sorters on. “We’re gonna take ‘em down, it’s not gonna be an issue,” says Michael Genao, a 22-year-old sophomore sorter with a linebacker’s build. “I guarantee it,” he adds, as he paces between his teammates, the last few bites of a chocolate donut in his hand.

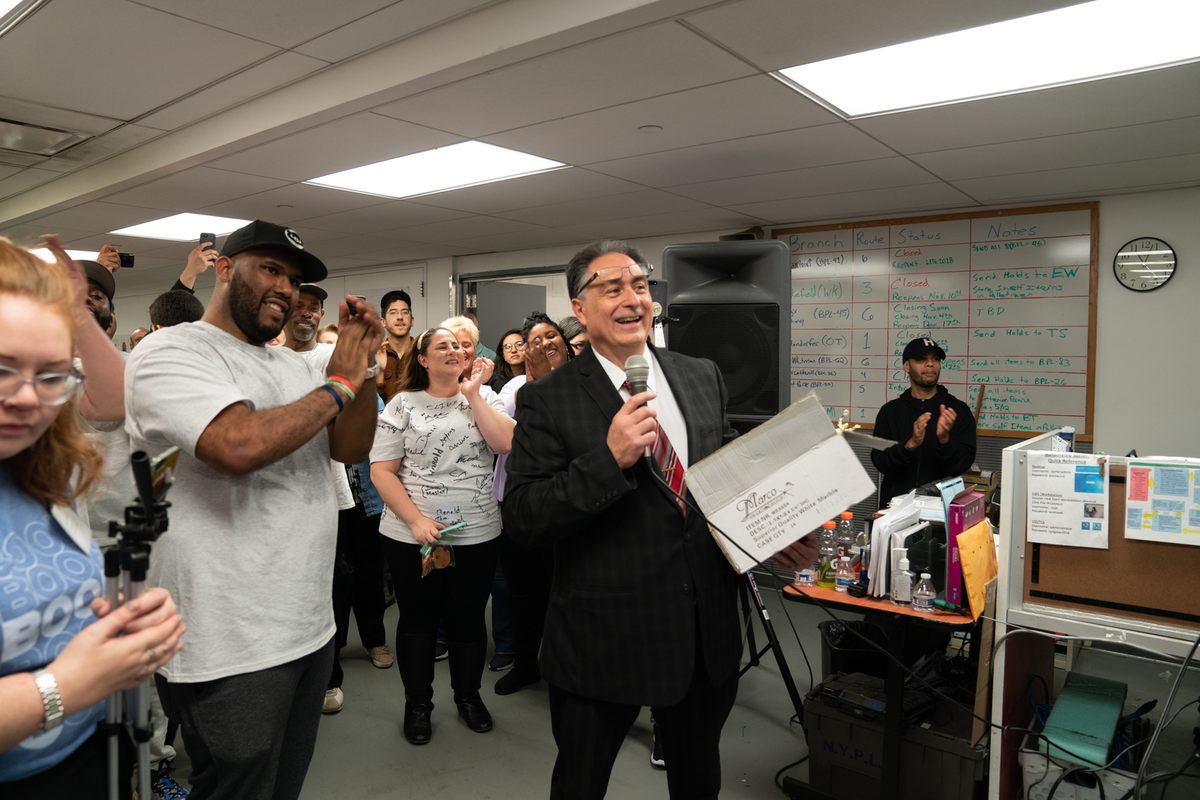

“You guys are the best in the world,” Magaddino assures his team. “I know you’re gonna prove it today. So the only thing I ask is that you give it 100 percent, and when your hands start cramping, just move on, get through it. It’s only an hour.”

The sorters take their places, two to a station. Miguel Roman, Manager of Automatic Distribution, reminds them, “We have no malice, they just have what we deserve.” As observers are escorted to a safe viewing distance, away from where new batches of books arrive by motorized cart, Kanye starts booming, red lights start spinning, gears start churning, and books start flying.

The belt on the machine goes by at 1.5 meters per second, which looks faster than it sounds. It’s covered with square pads, and the idea is to get one book, properly oriented, onto each, which carries it under a bright red barcode scanner. Then, after a quick hairpin turn, they head down a long straightaway lined with bins, each marked for a different branch. The system is smart enough to know just where to deposit each item without slowing.

In each sorting team, one member stacks arriving books, while the other deftly shuttles them onto the pads. It’s a simple proposition but a complicated task, requiring the nimble dexterity and improvisational flair of a jazz drummer. The sorting teams are in sequence along the belt, so not every pad is unoccupied as it passes by—the pattern is always changing. Sometimes, five open pads roll by in a row, allowing Angel Cortez to lay books down at evenly timed intervals, gently flicking them so that each one lands with an audible “thwack.” But just as his wrist locks into rhythm, it’s now every other pad that’s open, so he adjusts. Then it devolves into a random free-for-all, and it becomes far easier to miss one—or several. Missed pads are inevitable, sure, but each one chips away at that goal of 12,800.

The pads’ unpredictable patterns, however, are just the beginning of the sorters’ problems. Then there’s the books themselves, encompassing a remarkable range of sizes, weights, shapes, and textures. There goes a thick, weathered copy of The Odyssey, curling at the edges. Here comes a flimsy Japanese manga comic, and then a hardcover, slick under library laminate. Each of these requires a different scoop, a different toss. And then there are the devious DVDs. At one point one of these thin, bouncy interlopers trips Cortez up, and a copy of Black Panther hits the floor. The book sorter is not an assembly line worker. He is more like a juggler who cannot choose his pins. Cortez’s face trembles with sweat and concentration.

Roman, the distribution manager, assures the spectators that none of this is for show—every book here, and that Black Panther DVD, will be dropped off in Brooklyn later this afternoon. On the other side of the barcode scanner, books are automatically directed neatly off the conveyor belt and into bins labeled for Windsor Terrace, Sheepshead Bay, Ulmer Park. Full bins are carried outside to a truck, the next axon in New York City’s knowledge distribution system. And for all of the knowledge about to be acquired, most readers will never have any idea how it works. Akkim Thomas, a 24-year-old sorter, says he discovered a new favorite book on the belt: Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man.

As they stream by, the books are a reflection of the city itself. There’s The Very Hungry Caterpillar, for a child just learning to read. Then there’s a slew of how-to and self-help, from SAT prep to Economics for Dummies to a five-copy stack of Easy Vegan Baking. To Kill a Mockingbird, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, and As I Lay Dying are there for the literary types, alongside biographies of Richard Nixon, Mikhail Gorbachev, and Frida Kahlo. The Autobiography of Malcolm X, Barack Obama’s Change We Can Believe In, and a book of essays on race called We Can’t Breathe join the Twilight series, a chunky Ayn Rand opus, and lots and lots of Lee Child thrillers. It’s like a look into New York City’s mind, through the 8.6 million minds that compose it.

Then, as sudden as the “thwack” of a perfectly placed book, the machine halts. The sorters can’t even raise their exhausted arms to celebrate. Their total is 12,330 books in one hour—that’s, astonishingly, over 96 percent of the machine’s capability. As someone calls for tequila, Cortez just tries to catch his breath. “I wish I could clap,” he says, hunched and panting, “but my arms are gone.” King County isn’t due to compete for a few hours, and the specter of their last-ups looms over every recited statistic and sweaty bro-hug. As if preparing for the worst, Magaddino surprises the team by announcing that the NYPL has selected them for a leadership award. It’s nice, but not what they came for. They want to be champions. No one knows it yet, but the outcome will be decisive, a blowout, even—12,330 to King County’s 10,007. The series is locked up at three apiece. That makes next year Game 7.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook