Ancient Trees Were Bafflingly Complicated, and Scientists Don’t Really Know Why

Tree rings are so much simpler.

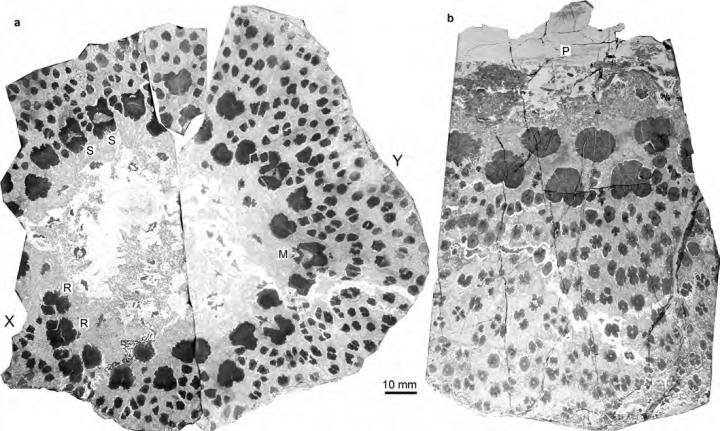

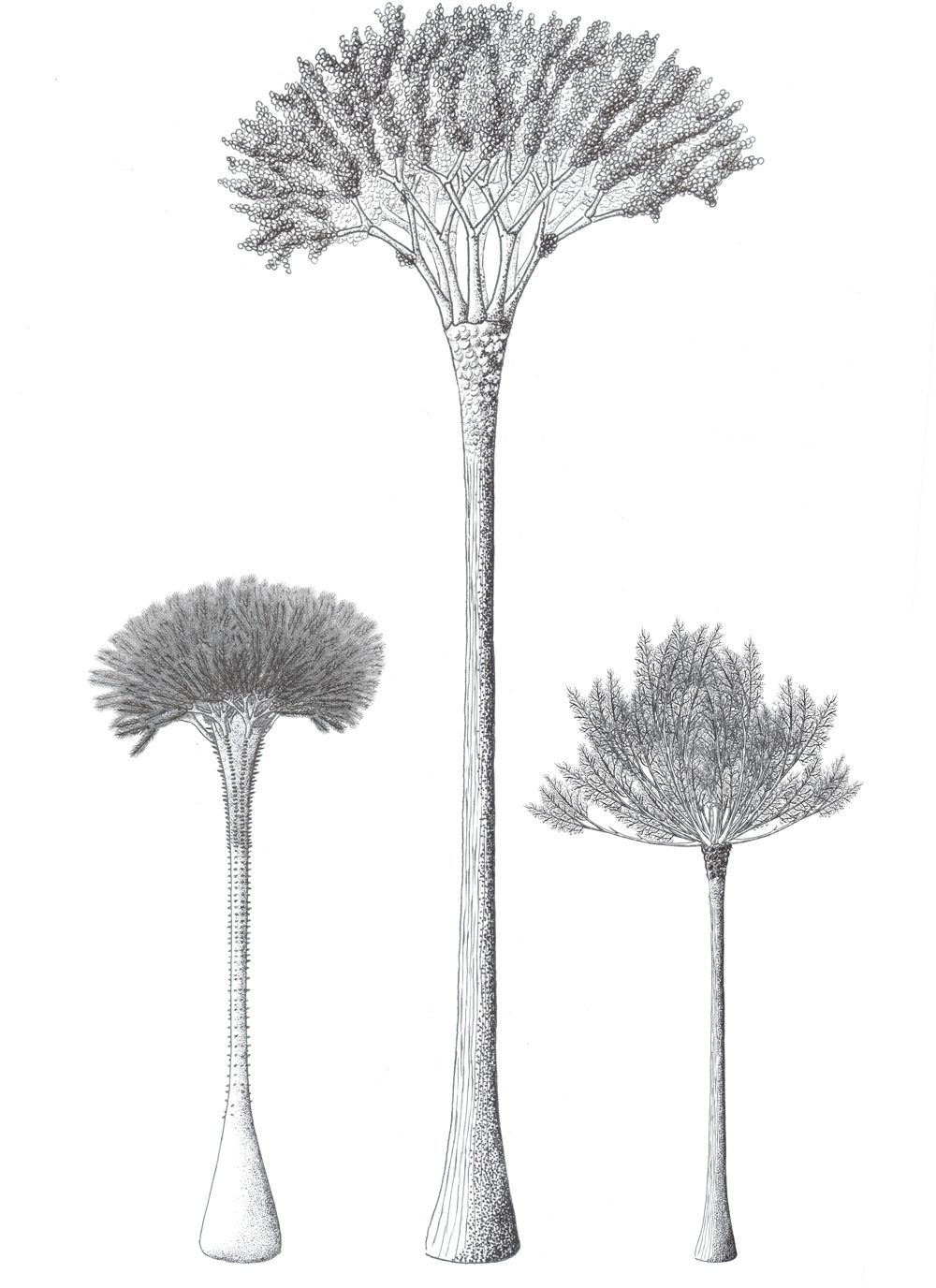

In the cross-section of a tree trunk, each ring represents a single year that the tree has been on the planet. The appearance can be intricate but the underlying pattern is simple, clear—elegant, even. But it wasn’t always this way. Ancient trees, scientists say, were way more complicated. A fossilized early tree, belonging to a group known as cladoxlopsids, that grew in what is now northwest China around 374 million years ago, revealed a tangled web of trunks—hundreds of individual strands, each with their own set of concentric growth rings.

Within this single large tree were hundreds of “mini trees,” whose trunks split apart and then repaired themselves as the tree grew. “The tree simultaneously ripped its skeleton apart and collapsed under its own weight while staying alive and growing upwards and outwards to become the dominant plant of its day,” Chris Berry, who coauthored a study on the fossils in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, said in a statement. It’s not yet known how this unusual structure would have affected the amount of carbon these trees were capable of caching from the atmosphere, which was the primary focus of this research.

The smaller trunk structures, Berry said, would have worked like “a network of water pipes,” transporting water from root to leaf, as opposed to the single-column structure of modern trees. The “pipes” are arranged only in the outer couple of inches of the trunk, and the core itself is entirely hollow. This all begs the question, Berry said, of why older trees seem so much more complicated than their modern equivalents.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook