Forgotten Notebooks Chronicled the Lives of Congolese Trees for 20 Years

The data could help biologists understand how climate change is affecting forests.

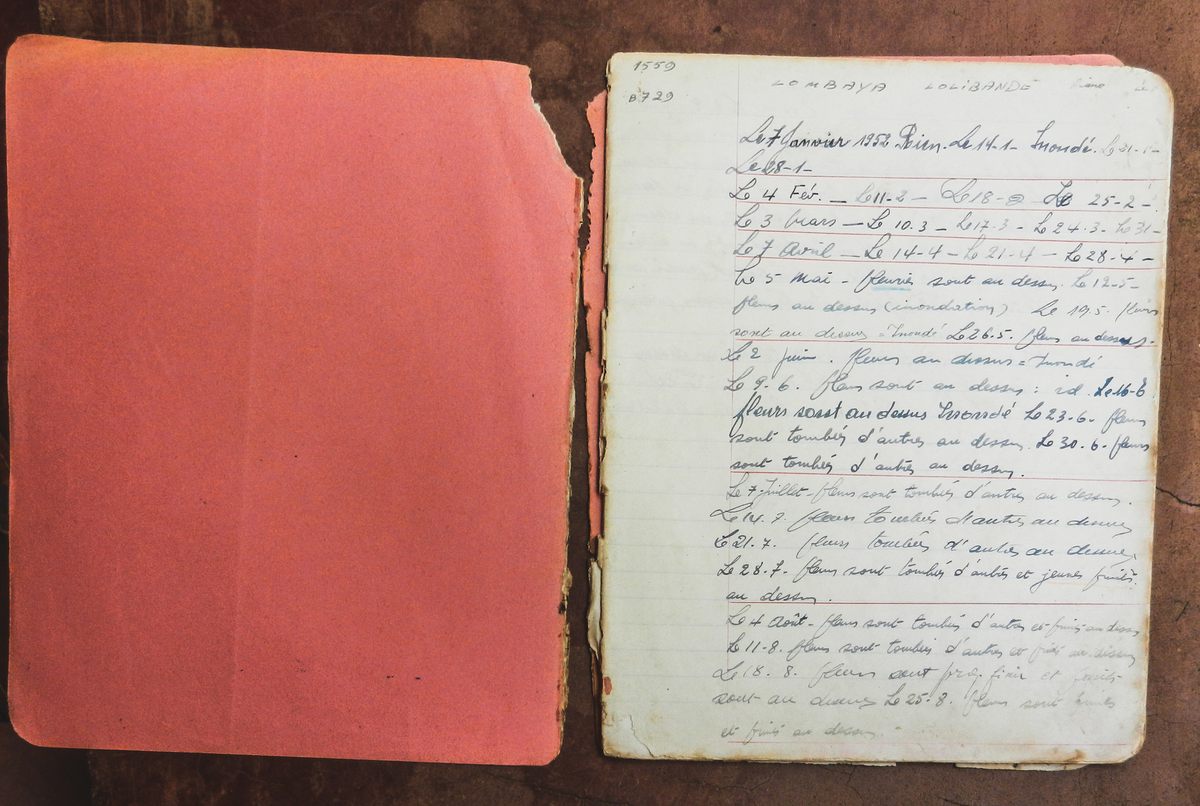

For close to 60 years, a set of notebooks sat unused in the herbarium at the Yangambi Biological Station in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. During the colonial era, this was an agricultural research station, the National Institute for Agronomic Study of the Belgian Congo, or INEAC. Every week for two decades, from 1937 to 1958, biologists at the station observed 2,000 individual trees and recorded whether they had flowered, fruited, or dropped their leaves. As The Guardian reports, the scientists scrawled their observations in small notebooks and coded them into larger logs, creating a detailed record of forest life during the final decades of Belgian occupation of this part of Africa.

When Koen Hufkens, an ecologist now affiliated with Ghent University in Belgium and Harvard University in the United States, arrived at the station in 2013, the documents had been overlooked for years. The roof of the herbarium was broken, and the notebooks had been damaged by water and nibbled away by rodents. But there was still valuable information inside. Hufkens pulled them together and set about saving the data gathered more than half a century before.

Why would scientists today care about mid-century Congolese trees? The forests in this part of the world have been relatively little-studied compared to the forests elsewhere, in part because of the political instability and military dangers of this region. But the rain forest in Africa, which covers more than 2.4 million square miles, is one of the most important carbon sinks on Earth, as it absorbs carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and locks it away in organic matter, which helps regulate the Earth’s climate. The project that Hufkens was originally working on when he arrived sought to better understand the relationship between carbon storage and biodiversity in Yangambi.

Like all ecosystems on Earth, the rain forest in Africa is being affected by climate change. That part of the world is beginning to dry out, so scientists want to understand how that will change the forest’s ability to store carbon. To do this, they need to know how the plants grow, drop their fruit and leaves, and eventually die, and how that has changed over time. The information trapped in those old, forgotten notebooks might contain some clues.

Observations like these—weekly data for 500 species of trees over 20 years—is hard to come by, says Hufkens. (Imagine trying to get a research grant for that project now.) The data from 60 to 80 years ago can “provide baseline measurements to which to compare the state of the forest and/or its response to climate change,” he says. “These measurements currently do not exist, and only historical data can fill in this knowledge.” The project he and a team of partners are now working on, called COBECORE (or “Congo basin eco-climatological data recovery and valorisation”), aims to extract data from the analog archives of INEAC—to store it all in a formal archive, not a crumbling herbarium.

First, the analog records need to be transformed into digital data, a painstaking process. After he found the tree data in the herbarium, Hufkens scanned the record books and enlisted help on Zooniverse, a platform that connects scientists with amateur researchers.

The records books contain a sort of code, of faint, penciled lines that chronicle the trees’ lives. Solid lines and cross-hatched marks indicate events such as fruiting and leaf fall, while an X stands for a tree’s death or removal from the study. Volunteers coded each of these marks so that a computer could read them and translate them into a digital database.

That’s just the beginning of unlocking the value of this data, though. Hufkens and his colleagues also need meteorological and weather data to start to understand how environmental changes might have affected the trees’ growth. The INEAC archives that COBECORE is digitizing are vast. But ultimately these old, almost entirely lost records may be able to help scientists see into the future of the Congo’s forests and understand how they might react to the challenges to come.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook