How Island Evolution Forged a Bizarre Mammal in Ancient Madagascar

Back when reptiles were all the rage, Adalatherium really stood out.

In July 1999, David Krause was enjoying the balmy winter weather of Madagascar as he dug in the dirt for dinosaurs. The island’s soil was fertile ground for life in ancient times. At the end of the Cretaceous period, 66 million years ago, Madagascar—already an island at that point, having chipped off of a drifting India some 20 million years prior—crawled with the legendary reptiles of the age, from meat-eating theropods to a 20-foot-long constrictor snake.

Which is why three years later, when Krause opened a plaster jacket that contained the fossils from the dig, the last thing he expected to find was a mammal.

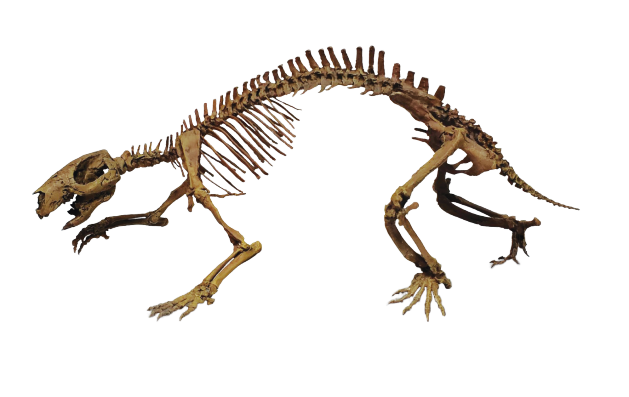

Yet there it was. Tucked into the mold, along with a small, ancient crocodilian, was Adalatherium hui—a stubby-tailed mammal from the Cretaceous, preserved exquisitely after its demise in a mudslide. The oldest mammal yet found south of the equator, Adalatherium had a unique set of characteristics that set it apart from all other living animals at the time, as well as Gondwanatheria—the mysterious mammals that evolved as the supercontinent Gondwana broke apart.

“Once the jacket was open, I recognized an elbow joint and knew it was mammalian,” says Krause, a paleontologist at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science and lead author of the paper. “ I didn’t sleep for two days, I was that excited.”

Studying the fossil remains of Adalatherium took nearly 20 years, as researchers tried to decipher every twist and turn in its strange morphology, from its toes to its teeth. Last week a new paper was published in the journal Nature, describing the find.

Scrawnier and more modern looking than their giant, scaly contemporaries, Cretaceous mammals were few and far between—especially in the Southern Hemisphere, which has fewer, and less scrutinized, fossil deposits than the Northern Hemisphere. The mammals that preceded an asteroid’s impact in modern-day Mexico, catalyzing the mass extinction event that killed off the dinosaurs, were generally eensy—a trait helpful for hunkering down to survive a global cataclysm, but troublesome when it comes to finding fossils. Adalatherium was a clear exception to that rule.

“It was a giant in its time, in the sense that during the Cretaceous, most mammals were shrew- or rat-size,” Krause says. “This thing is about 100 times larger than your standard house mouse.”

Adalatherium was a product of the island effect, which posits that large creatures shrink on isolated landmasses, while little critters get big. Perhaps inspired by a couple of reptilian goliaths that resided on Cretaceous-era Madagascar, Adalatherium grew to the size of a small dog.

Besides its unusual size, Adalatherium had a bevy of traits that make it an “outlier” on the evolutionary timeline, even when compared to the oddball fossas, lemurs, and aye-ayes that now inhabit the island nation. With forelimbs tucked close together underneath its body but hind limbs that splayed out on either side, it was a walking paradox. Among other things, it had a hole in its skull just above its nose that paleontologists still don’t fully understand—even after two decades of study and analysis. Adalatherium also boasted two pairs of upper incisors—and back teeth that defy explanation.

“The teeth are the standard thing to look at across early mammalian evolution,” Krause says. “These teeth are truly weird. There’s just nothing like them in any living or extinct mammal.”

When the asteroid hit, Adalatherium was among the many mammals wiped from the Earth. But Madagascar’s unique modern fauna evolved nonetheless.

How, you ask? Krause suggests that life may have found a way on large rafts of vegetation, drifting over from Africa—a theory that’s been floated for various combinations of species and continents. Madagascar is a particularly appealing subject given its close proximity to Africa, and the amount of flotsam that still washes off the east coast of the continent after heavy storms.

“If this happens within our puny lifetimes, what are the chances of success over 65 million years?” Krause says. “The improbable becomes much more probable with the passage of time.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook