The Forgotten Italian Tradition of Building Monumental Food Palaces

Then destroying them in a literal hunger games.

In 1768, Austrian princess Maria Carolina married Ferdinand IV, the king of Naples. To celebrate, they had a magnificent, fake fortress built in front of the Neapolitan royal palace and decorated with delicious food. At a signal from the king, a mob of Neapolitan commoners waded through a moat stocked with live fish, slipped through the mud, and grabbed all the food, to the delight of the noble spectators.

The event was a tradition of Naples and other Italian cities, because nothing caps off a royal wedding or holiday like watching hungry people fight for food. Temporary temples, pyramids, and castles were plastered in roasts, bread, and cheese, which the poor risked their lives to gather.

These Cuccagna festivals represented an earthy paradise where no one went hungry. For centuries, European poets and artists described the magical land of Cockaigne, or Cuccagna, where the lazy were king and food fell from the sky. One 14th-century poem described rivers of milk and honey. Unpleasant reminders of daily life, such as bad weather or fleas, didn’t exist.

Cuccagna festivals brought the dreamworld of Cockaigne to life. But instead of paradise, they were demonstrations of wealth and power that often descended into brutality.

Creating a real-life Cockaigne meant displaying massive quantities of fruit, cheese, meat, and bread in beautiful configurations, Marcia Reed, the chief curator at the Getty Research Institute, explains. But not all the bounty was dead. Reed, who also curated the GRI’s The Edible Monument: The Art of Food For Festivals exhibition, notes that Cuccagna also featured hunts of live pigs, bulls, and birds.

In 1716, Bologna had a Cuccagna-inspired Feast of the Roasted Pig. Men with spears pursued loose bulls, while commoners climbed “Cuccagna trees” in the gardens. The trunks were covered in grease, so only the most nimble could pluck the whole, live birds tied or nailed to the branches.

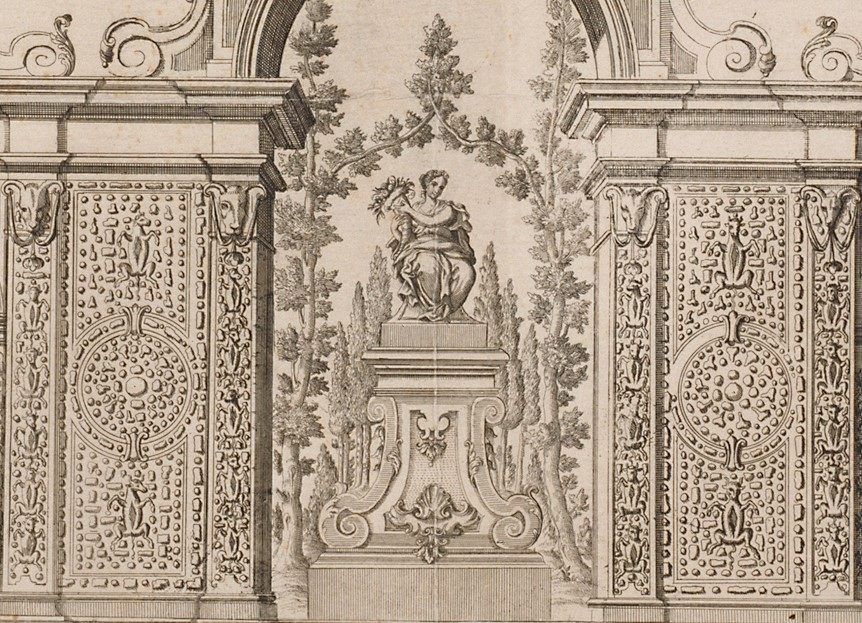

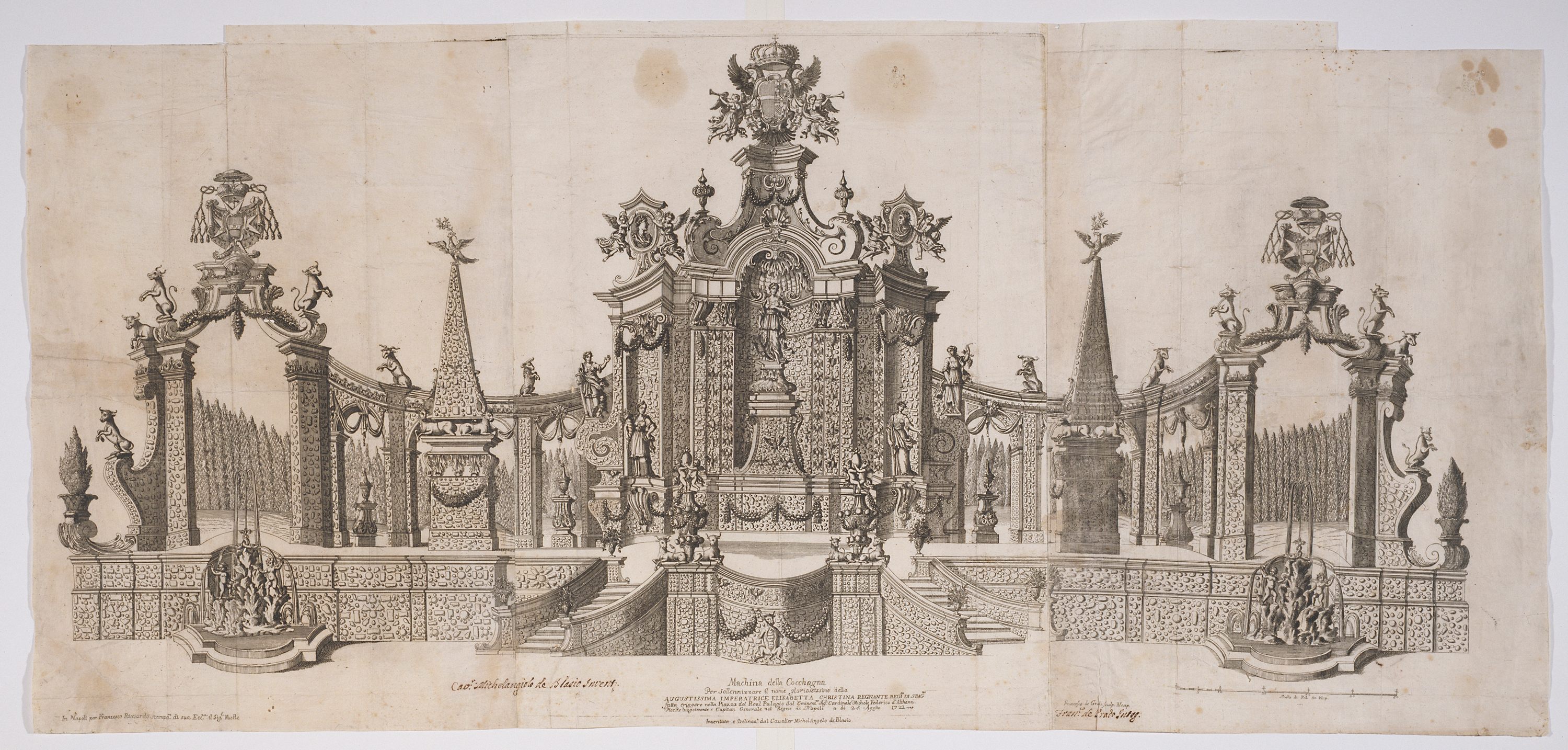

The most elaborate Cuccagna festivals were always in Naples. The first Cuccagna displays were more like parade floats. But by the 18th century, they were stationary. For the name day of Holy Roman Empress Elizabeth Christina, a massive, stage-like Cuccagna was built in 1722. Statues of gods and angels adorned each plinth, but a closer look reveals an unusual embellishment. Studding every wall and column, as Reed describes in Edible Monuments, were “breads, pastries, swags of fruit and vegetables, livestock and fowl.”

Cuccagnas were so popular that they were used to celebrate everything from saint’s days to royal birthdays. Nobility usually sponsored the monuments, and local craftsmen and farmers set up the edible embellishments. Occasionally, fireworks accentuated the beautiful scenes.

In 1747, a Cuccagna for the birth of Prince Philip, son of Charles VII, king of Naples, featured a fabulous building on a hill in front of the royal palace. The building’s balustrades and the paths up the hill were made of cheese, cows and goats roamed about, and fountains burbled with wine. Two greased Cuccagna trees, which look more like poles, have suits of fine clothing attached to the top. Surrounding the vision of perfection, “the poor wretches of the Neapolitan streets,” as Reed describes them in Edible Monuments, sprint towards the vision of food and plenty.

“I think one of the sad elements [of Cuccagna] is that the people running and getting the food were very poor and very hungry,” says Reed. The city elite watched from their balconies, but the Cuccagna was meant as entertainment for the whole city. Reed emphasizes one positive aspect: Many hungry people got their hands on food.

In 1764, a famine in Naples contributed to the demise of Cuccagna festivals. That year, hungry Neapolitans sacked the Cuccagna before the king’s signal. Disgruntled authorities decided the events weren’t worth the trouble, and over the next few decades, they disappeared.

It may have been for the best, as the Cuccagna often turned bloody. Stampeding citizens crushed each other and fought over food. One Neapolitan king, Charles III, set up a fund for widows of Cuccagna casualties. Even the infamous Marquis de Sade was horrified by the Neapolitan Cuccagna he witnessed in 1776, calling it a display of barbarity and chaos. The princess Maria Carolina reportedly expressed horror when she saw live animals being torn apart at her wedding Cuccagna.

The philosophy of the Cuccagna was always excess. “Too much was never a concept they absorbed,” Reed says of Neapolitans, whose idea of a good time was “More fireworks, more food, more fountains.” While there aren’t many similar events these days, Reed notes that food is still a central theme at festivals. She points to the Macy’s Day Parade: It’s all about a giant turkey float, even if no one tries to rip it to shreds every year.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook