The Tiny Building That Pays Tribute to a Larger-Than-Life Civil Rights Leader

Daisy Lampkin’s brick house is the newest addition to a beloved, shrunken cityscape in Pittsburgh.

If you’d driven along Pittsburgh’s Webster Avenue decades ago, you may have caught a glimpse of Black suffragist and civil rights activist Daisy Lampkin at her home. The red-brick building on the corner stretches three stories tall, with ornamental cornices and rows of windows. It was Lampkin’s house for four decades, when she wasn’t traveling for work with the NAACP. The building still stands today—and now, so does a miniature version of it.

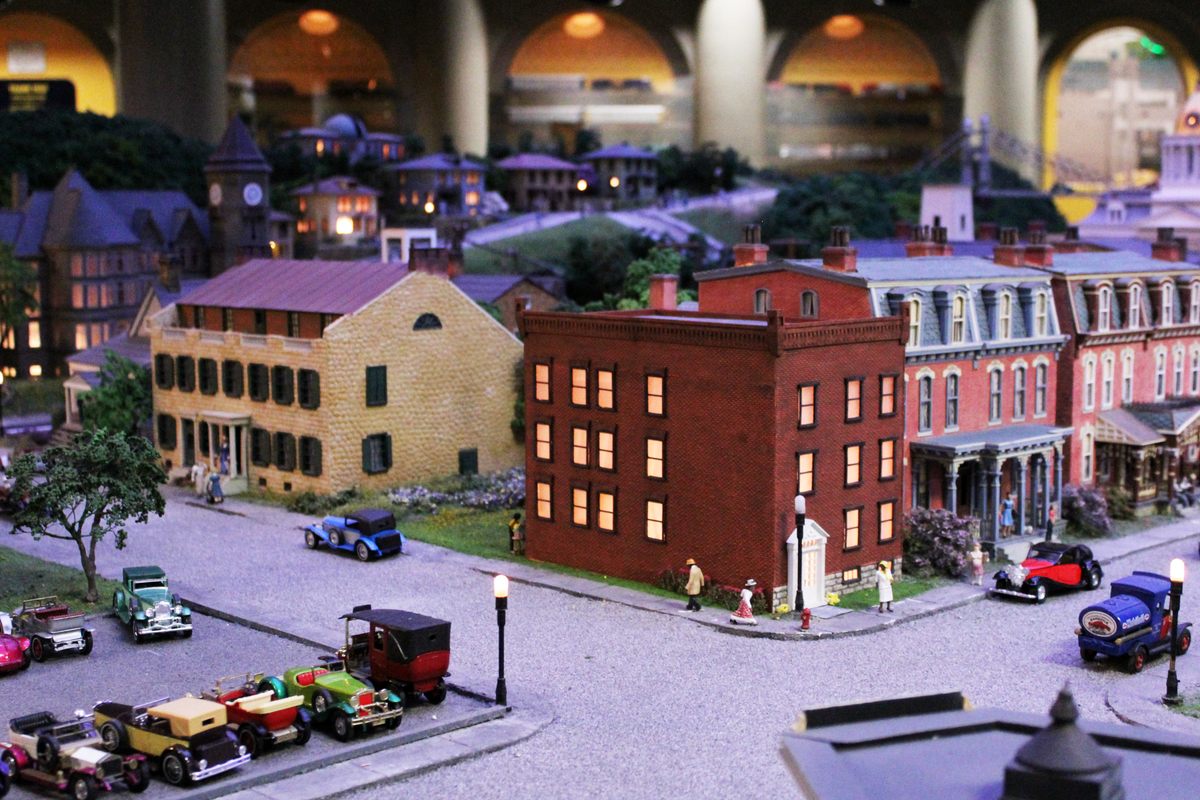

An eight-inch model of Lampkin’s residence is the newest addition to Carnegie Science Center’s century-old Miniature Railroad & Village, where a Pittsburgh-themed model is added each year. Lampkin, only an inch tall, is dressed in yellow and white—the colors of suffrage—and holds court on a sidewalk, as if ready to give an impromptu speech.

Lampkin’s figurine joins miniatures of businessman Gus Greenlee, newspaper publisher Robert L. Vann, architect Frank Lloyd Wright, and photographer Teenie Harris, among others. The new model pays tribute to the 100th anniversary of the 19th amendment, which granted women the right to vote (though, in practice, it would be decades before non-white women were able to fully exercise this right, and voter suppression still disproportionately affects communities of color). Spotlighting the tireless advocacy of Lampkin, an “often-overlooked famous suffragist,” was “the perfect fit,” says Patty Everly, curator of historic exhibits for the science center.

Carnegie Science Center program assistant Nikki Wilhelm suggested a tribute to Lampkin. During an internship, Wilhelm stumbled across Lampkin’s story in the archives at Heinz History Center. Then more recently, she noticed Lampkin’s home in an article about important buildings for Black history in Pittsburgh, and it all clicked. “This would be perfect for the railroad,” Wilhelm says. “She’s so influential, and she’s never come up in any history book that I’ve read.”

Lampkin was “one of many Black women who were very active politically and socially going back to the late 19th century,” says Samuel W. Black, director of African American Programs at Pittsburgh’s Heinz History Center, an affiliate of the Smithsonian Institution. “They were forming organizations, and many of these organizations were maybe social organizations, but they all had a political agenda,” Black says. Lampkin is “one of my favorite people,” Black adds. “There’s so many layers to her.”

In her lifetime (1883-1965), Lampkin pushed for civil rights locally and nationally. Beginning in 1912, she led groups of Black women in street-corner campaigns and consumer protests. For decades, she served as president of the Negro Women’s Equal Franchise Federation, later named the Lucy Stone Civic League. In 1924, she was the only woman in a group of African Americans who met with President Calvin Coolidge to discuss racial violence and discrimination. In 1941, she raised $2 million worth of Liberty Bonds to support WWII.

During Lampkin’s tenure as vice president, the Pittsburgh Courier—which Black calls a “crusading newspaper for civil rights”—became one of the nation’s most widely distributed Black papers. At the NAACP, Lampkin worked her way up from regional field secretary to national field secretary to a member of the Board of Directors and became the first woman on the Board. She was named the NAACP Woman of the Year in 1945 for building the largest membership enrollment in the group’s history and raising more money than any other executive.

“Racism existed very thickly in Pittsburgh in almost every facet of life,” Black says. “The reason you had these organizations is because the struggle still existed,” Black adds, reflecting on educational discrimination in Pittsburgh, where the public school system didn’t hire a full-time Black teacher until 1937. “These were the types of concerns that Black women knew and understood because this affected them directly.”

Lampkin managed it all from her home in Pittsburgh’s Hill District. Today, a blue-and-yellow Pennsylvania historical marker honors its place in history. The home was Lampkin’s headquarters for phone calls with people like lawyer Thurgood Marshall (who would go on to become the first Black Supreme Court justice), activist Roy Wilkins, and politician K. Leroy Irvis, says Lampkin’s grandson, Dr. Earl Douglas Childs. “She was looking to help people or to advance the cause, and she was the facilitator in many ways,” Childs says. “She was a doer. She was a worker.” Childs remembers the home where he grew up as a place for his grandmother’s work (he recalls seeing “Stop Lynching” buttons around the house) but also for simple pleasures (like games and family breakfasts).

Like many Pittsburgh kids, Childs relished his visits to the Miniature Railroad & Village; seeing his family home on display as an adult brought tears to his eyes. “It was such an honor. I’m so thrilled that she is getting the recognition now and that I’m alive to see it,” he says.

The artisans at Carnegie Science Center scoured newspaper records and sought expertise from the archivist of the Teenie Harris photography collection to get every detail just right for the plexiglass structure. The model has more than a dozen 3D-printed windows, and an ornate front door. The science center team used different washes of colors and dry brushing on brick-patterned plastic sheets to emphasize the brick-and-mortar details, Everly explains. The windows even glow, thanks to tiny light bulbs that cycle through a day scene and a nightscape.

“What would life have been like for Black people in Pittsburgh, especially Black women, if Daisy did not exist?” Black asks. “I don’t think Black Pittsburgh could’ve done without her.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook