Seeking the Truth Behind Books Bound in Human Skin

And the “gentleman” doctors who made them.

This story is excerpted and adapted from Megan Rosenbloom’s Dark Archives: A Librarian’s Investigation into the Science and History of Books Bound in Human Skin, published in October 2020 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

In the summer of 1868, a 28-year-old Irish widow named Mary Lynch was admitted to Ward 27 of Philadelphia General Hospital. Nicknamed Old Blockley, this huge facility for the poor in West Philadelphia contained a hospital, an orphanage, a poorhouse, and an insane asylum. Just four summers prior, some walls in its Female Lunatic Asylum—“being undermined by workmen”—collapsed, killing 18 women and injuring 20 more. Patient care at Blockley was a far cry from physician house calls for the wealthy; it was a place for the desperately ill poor, and Lynch’s tuberculosis (then called phthisis) put her in a dire situation.

Lynch’s family did what they could to make her comfortable while she suffered, visiting her with ham and bologna sandwiches in tow. No one seemed to notice the white specks on the lunchmeat—a telltale sign of roundworm infection. The trichinosis she contracted from those sandwiches compromised her already weakened state.

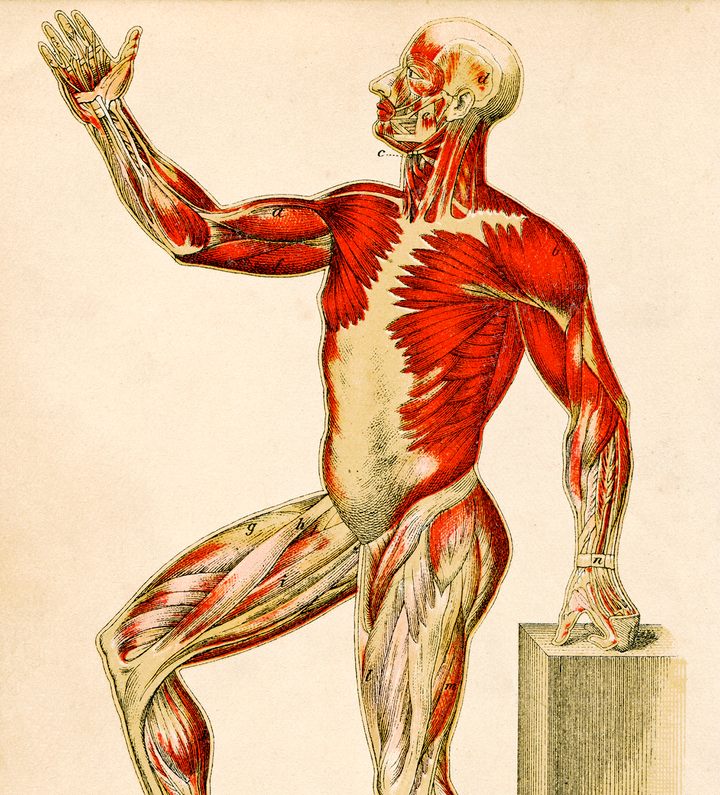

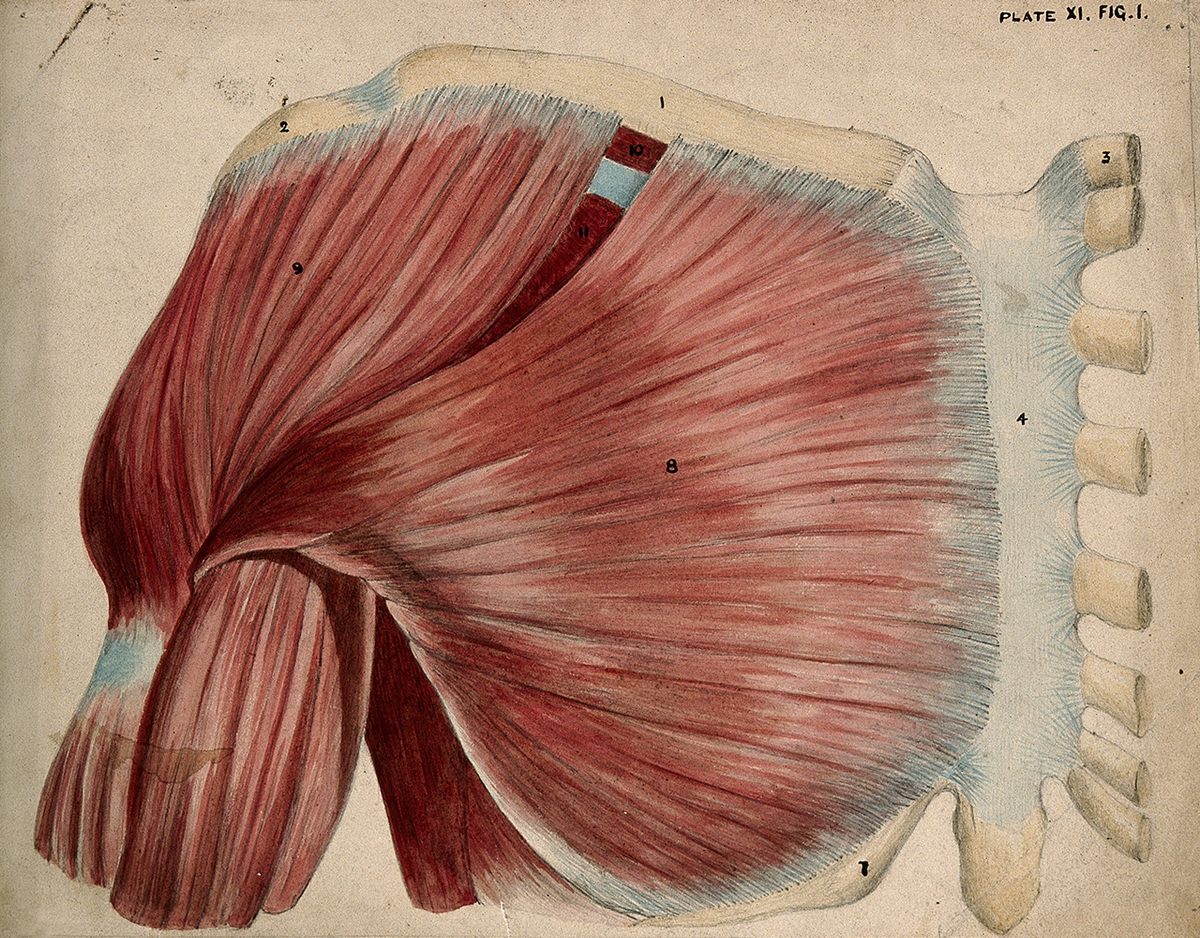

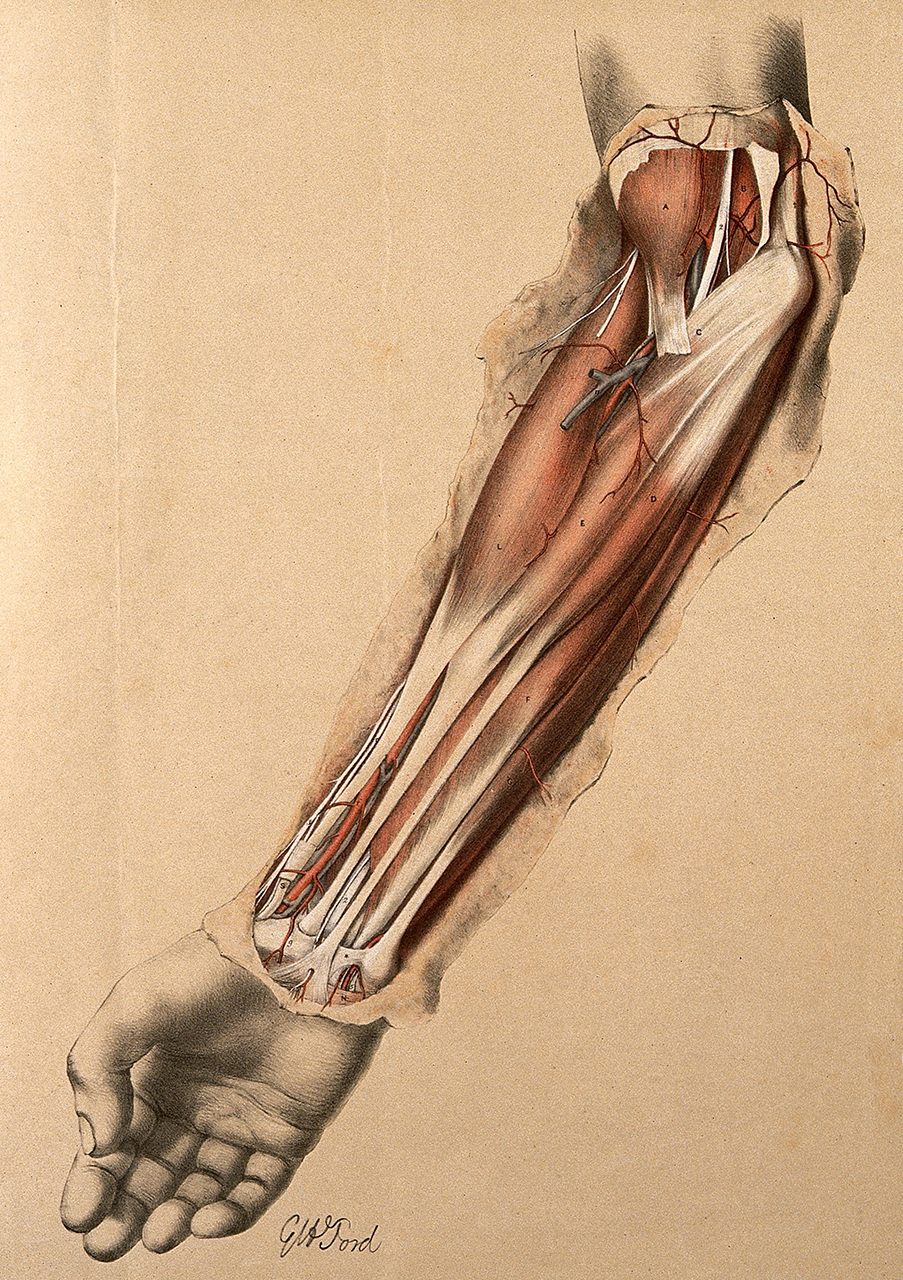

Nurses attended to Mary Lynch over six months as her body withered away to a mere 60 pounds. Eventually she succumbed to the two diseases wreaking havoc on her frail frame. When the young doctor John Stockton Hough first encountered Lynch, it was on his autopsy table in January 1869. In an article in The American Journal of the Medical Sciences, “Two Cases of Trichiniasis at the Philadelphia Hospital, Blockley,” Hough reported that when he opened her chest cavity to observe her tuberculosis-ravaged lungs, he noticed that the pectoral muscles that he had sliced along the way had some unusual lemon-shaped cysts. Looking into his microscope, he realized that the cysts were teeming with Trichinae spiralis (worms) in various stages of development.

“Counting the number in one grain of muscle, the whole number of cysts were estimated to be about 8,000,000,” Hough reported, making Lynch’s the first case of trichinosis discovered in his hospital and—as far as he could find—in Philadelphia as well. It was during that autopsy that Hough removed the skin from Lynch’s thighs. He preserved her skin in a chamber pot and stored it for safekeeping while the rest of Mary Lynch’s body was dumped into a pauper’s grave at Old Blockley.

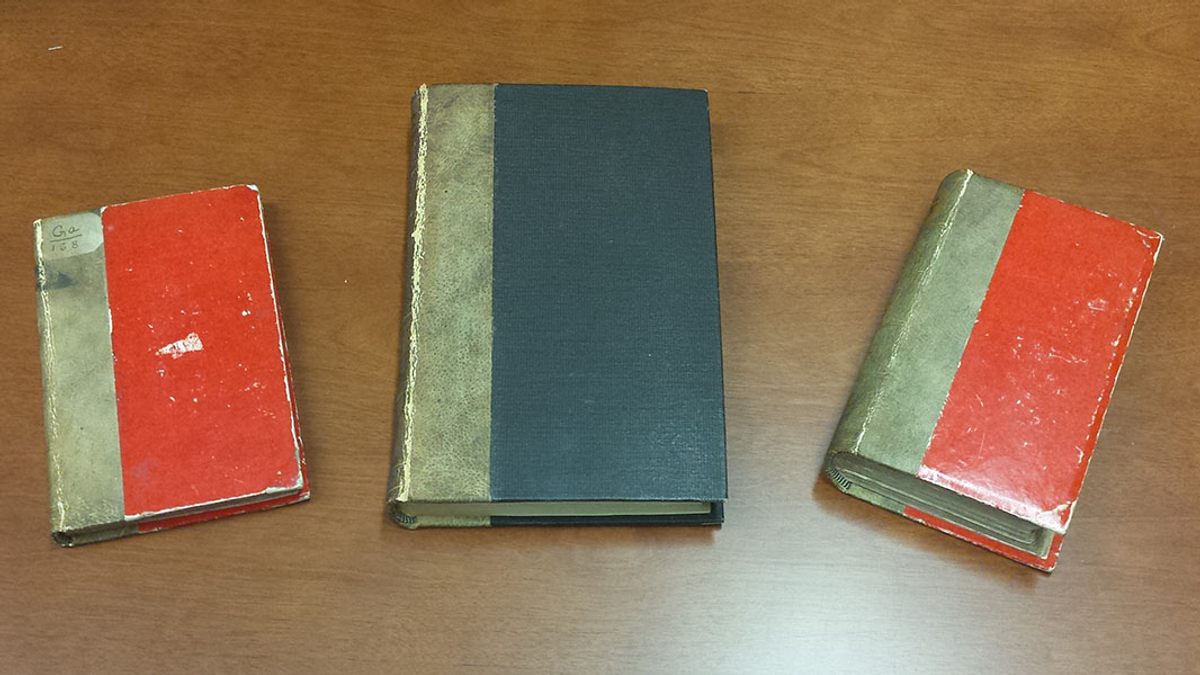

Decades later, Hough—by then a rich, well-respected bibliophile—used Lynch’s skin to bind three of his favorite medical books on women’s health and reproduction, including Louis Barles’s Les nouvelles découvertes sur toutes les parties principals de l’homme, et de la femme (1680), Recueil des secrets de Louyse Bourgeois (1650), and Robert Couper’s Speculations on the Mode and Appearances of Impregnation in the Human Female (1789). Hough had cultivated a specialty in women’s health beginning in his residency at Old Blockley, where he developed a speculum adaptable for vaginal, uterine, and anal use.

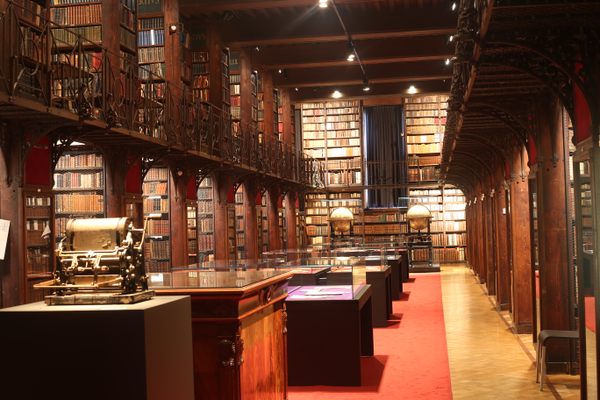

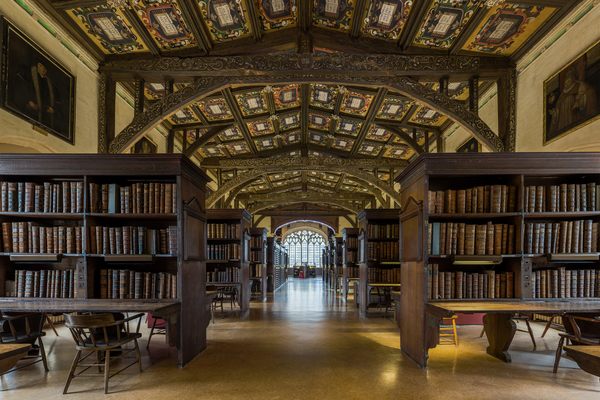

John Stockton Hough, like many gentlemen doctors of his day, enjoyed a classical education at the finest academies New Jersey had to offer before pursuing simultaneous degrees in chemistry and medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. During his residency at the Philadelphia General Hospital, he cultivated disparate clinical interests in reproductive medicine and parasitic trichinae. His family wealth and a lucrative private practice afforded him gentlemanly pursuits, and he began collecting rare books with vigor, particularly medical books from the dawn of the age of print. He traveled to Europe often, sending ahead to antiquarian booksellers a printed list of the medical incunabula he wanted to find; bibliophiles call these wish lists “desiderata.” He was invited to join book collector societies such as the Grolier Club in New York, established in 1884 to “foster the study, collecting, and appreciation of books and works on paper, their art, history, production, and commerce.” He delighted in showing off his collection in his luxurious home library in Ewing, New Jersey, to reporters, fellow bookmen, and (on Sundays only) his own children. With a roaring fire flickering off a bookshelf stuffed with rich leather bindings, he would pull down book after book, pointing out one “nugget,” “marvelous gem,” or “beauty” after another.

By the time Hough was 50, he had amassed a collection that was the envy of his fellow doctor bibliophiles; he estimated in 1880 that he owned around 8,000 books. His copy of Fabricius ab Acquapendente’s De formato foetu (1627) was rare to start, but Hough’s copy was made unique by its 30 painted folios illustrating fetal development. He also had a few examples of anatomical texts from the late 16th and early 17th centuries that featured anatomical flap illustrations, reminiscent of today’s children’s books, where flap after flap lifts to reveal the layers of body structures doctors would encounter as they dissected a cadaver. Few of these books survive today given the centuries of curious fingers folding their flaps. Hidden among these gems, looking much the same as any other book on the shelf, were the three works on reproduction bound in the skin of Mary Lynch. Hough died at age 56 after a runaway horse threw him from his carriage, and the bulk of his prized collection went to Hough’s alma mater, the University of Pennsylvania, and the library at the College of Physicians of Philadelphia.

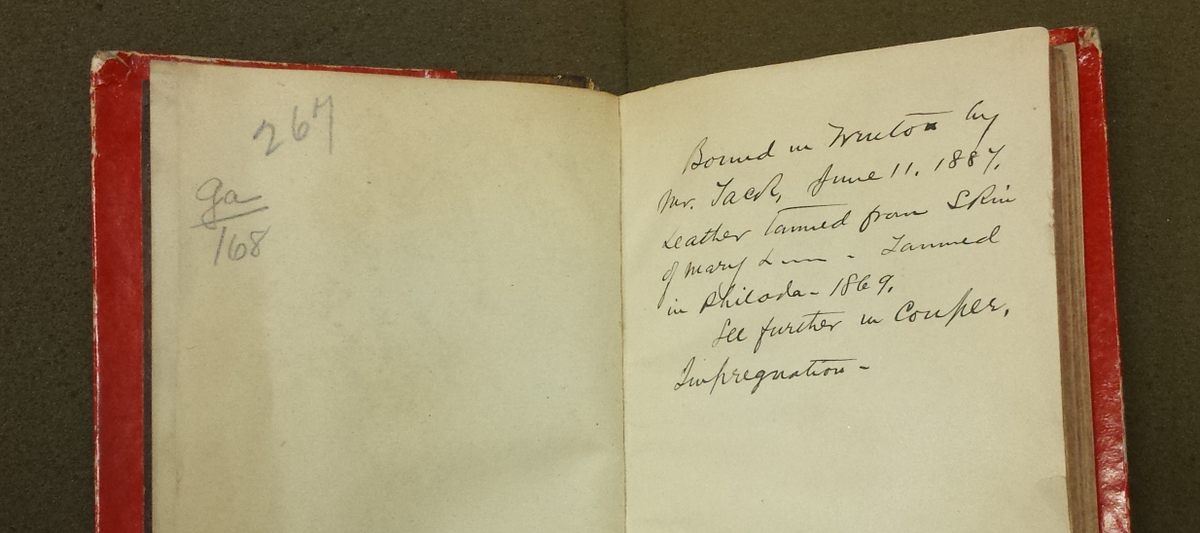

While the identities of most of the patients used by doctors to create human skin books are lost to history, the doctors who created them were often well respected in their fields, admired doctors and collectors occupying elevated social strata in a 19th-century United States clamoring for the legitimacy of its European counterparts. Unlike most doctors who created these books, Hough gave some identifying information about the source of his leather in his handwritten notes inside, referring to “Mary L___” in each of the three volumes made from her skin. It was this tidbit, plus her knowledge of Hough’s tenure at Old Blockley, that inspired the College of Physicians of Philadelphia librarian Beth Lander to dig into the Philadelphia General Hospital archives in search of the true identity of the woman who supplied the skin for three out of their five confirmed anthropodermic books.

This book is the biggest pain,” sighed John Pollack, a rare book librarian at the University of Pennsylvania. In my travels studying anthropodermic bibliopegy (a combination of the Greek root words for human [anthropos], skin [derma], book [biblion], and fasten [pegia]), I would soon become accustomed to this reaction from my fellow librarians. “A research library full of amazing stuff and people want to see this,” he said as he hefted the massive book in his hands.

Anthropodermic bibliopegy has been a specter on the shelves of libraries, museums, and private collections for over a century. Human skin books—mostly made by 19th-century doctor bibliophiles—are the only books that are controversial not for the ideas they contain but for the physical makeup of the object itself. They repel and fascinate, and their very ordinary appearances mask the horror inherent in their creation. Anthropodermic books tell a complicated and uncomfortable tale about the development of clinical medicine and the doctoring class, and the worst of what can come from the collision of acquisitiveness and a distanced clinical gaze. The weight of these objects’ fraught legacy transfers to the institutions where they are housed, and the library and museum professionals who are responsible for them. Each owner handles this responsibility differently.

A few years before, I had joined forces with two chemists and the curator of the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia to create the Anthropodermic Book Project. Our aim is to identify and test as many alleged anthropodermic books as possible and dispel long-held myths about the most macabre books in history. My team has so far identified only about 50 alleged anthropodermic books in public collections—including the five at the library at the College of Physicians of Philadelphia—and a few more in private hands.

I try to hedge a little about the types of titles that tend to be bound in human skin, as it takes only one confirmation of a certain kind of book to completely change our understanding of the universe of this practice, since there are so few of them. People often ask me if there are “sexy” human skin books, and I used to say no—until we tested a 19th-century printing of a 16th-century French BDSM allegorical poem, owned by that same Grolier Club to which Hough belonged, and lo and behold: real human skin. Even so, I have come to see certain traits that tip the scale toward whether an untested book might be real or fake.

To my eye, then, this doorstop at Penn had fake written all over it. It was Hough’s copy of the Catalog des sciences médicales (Catalog of Medical Sciences) from the Bibliothèque nationale de France. It contains lists of medical works housed at the library in that era, like a 19th-century library’s equivalent of a phone directory. It’s quarter-bound, meaning only one quarter of the book is covered in leather, around the spine, and the front and back covers of the book are more like what we would recognize as a hardcover today, with paper over board. It is so big that opening and closing over the years has put a lot of strain on the binding, which has developed red rot, an irreversible condition in which exposure to acids begins to break down the leather. The library covered it in a clear mylar jacket to stop the red rot from depositing bits of putative human leather on anyone who handles the book.

The real human skin books that our scientific team has verified over the years have content that was specifically chosen to match their macabre binding. The books that Hough bound in Mary Lynch’s skin were about women’s medicine, bound in the skin of a woman whose hide he held onto for decades before using it. So why would that same person use the world’s rarest binding material to bind a directory? Pollack, too, was incredulous: “I feel like he picked the most boring book off his shelf and said, ‘Oh, this will do.’” This book will always remind me not to lean too heavily on my initial instincts, because a few months prior to my visit, tests had confirmed that the binding of Catalog des sciences médicales is real human skin.

I might never know the full story behind this misfit skin book, but I slowly started connecting the dots to form a more complete picture of Hough as a gentleman collector. Hough was a bibliographer who loved compiling lists of desiderata, and he also attempted to quantify the world’s rarest medical books in lists. Inside the Catalog he wrote, “The Bibliotheque National [sic] in 1889 contained 15,000 incunabula of all kinds, of which a catalogue is being prepared, if 1 out of 30 books are medical there would be 500 medical books printed in the XV Century.” That kind of list-making might sound boring to me and John Pollack, but it must have been pretty exciting to Hough, as he was attempting to define the universe of medical incunabula and collect as many as possible. Above that note was another that read, “Bound with skin from the back-tanned June 1887,” and directly below that, “bound Jany. 1888.” But there is also a note on that same page that reads “Stockton-Hough, Paris, Sept. 1887.” It is possible he went back to this page multiple times to update these notes.

The notes in the Catalog reveal that the skin was tanned and the book bound in quick succession, without the intervening decades of storage like the other Hough anthropodermic books, which leads me to wonder whether the inveterate bibliophile, having finally run out of saved skins to bind books, procured more skin to try his hand at binding books himself. The Catalog lacks the gilded embellishments and other signs of skilled craftsmanship of the other specimens that he had created. Those specimens all appear to have been made by the same craftsman. The red rot now affecting the book could be a side effect of some of the newer tannins being used at the time, or it could have been made by someone with less expertise. Perhaps the Catalog was the result of Hough’s attempt at bookbinding—perhaps he truly did, as Pollack joked, pull any old book off the shelf and say, “This’ll do.”

The College of Physicians of Philadelphia owns a fourth anthropodermic book, also about reproduction, from John Stockton Hough’s collection: Charles Drelincourt’s De conceptione adversaria (1686). On the flyleaf inside, Hough’s handwritten note reveals that it was bound in Trenton, New Jersey, in March 1887, using the “skin from around the wrist of a man who died in the [Philadelphia] Hospital 1869—Tanned by J.S.H. 1869. This bit of leather never boiled or curried.” To curry, in this case, means dressing the already tanned hides by soaking, scraping, or dyeing to achieve a certain look and feel.

I returned to Hough’s article on the two cases of trichinosis. Mary Lynch was the first. The other is described as an “intemperate” 42-year-old Irish laborer he called “T McC,” who died in February 1869, emaciated and having suffered from chronic diarrhea (just as Mary Lynch had). Hough found Trichinae spiralis during his autopsy as well. Could he be the man whose wrist supplied the binding for the Drelincourt book?

A dig through the Philadelphia General Hospital’s Male Register turned up a Thomas McCloskey whose intake and discharge dates all align with those reported by Hough in his article. The timing certainly matches, but since Hough merely describes him, on the book’s flyleaf, as “a man who died in the [Philadelphia] Hospital 1869,” I can’t draw as bright a line there as Beth Lander could between Mary Lynch’s hospital records and the “Mary L___” in Hough’s handwriting.

If your mental image of a doctor binding books in human skin is that of a lone mad scientist, toiling away in a creepy basement creating abominations, that would be understandable. But the truth about these doctors—and Hough wasn’t even the only one in Philadelphia at that time making human skin books—is much harder to square with our current perceptions of medical ethics, consent, and the use of human remains.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook