The Feminist Lunch That Broke Boundaries 150 Years Ago

For women, dining in public without men was revolutionary.

On April 20, 1868, a dozen women filed into Delmonico’s. The New York restaurant was the most famous in America, and the women were all middle- and and upper-class. But many of the women worked, which was an anomaly in the mid-19th century. And their lunch was even more of an anomaly: It was the first time American women deliberately dined in the public eye without the accompaniment of men.

At the time, American society was strictly segregated by sex, and the streets were a male sphere. A middle- or upper-class woman alone in public attracted intense attention, and working women were often invisible. For all women, a male companion was a necessary ticket into a restaurant. (Private dining rooms where solitary women could eat out of sight were the norm, and only for the most elite women.) According to food historian Paul Freedman, very few establishments accommodated women shoppers and travelers. In 1850s New York, for example, only a handful of ice cream “saloons” allowed women to eat by themselves.

But in 1868, reporter Jane Cunningham Croly was fed up. Charles Dickens was touring the United States, and the New York Press Club threw a dinner in his honor at Delmonico’s. Croly wanted to attend the Dickens dinner, scheduled for April 18. But the Press Club refused, even though she was a member. After she protested, the Club leadership relented, but they insisted that she and other female members stay behind a curtain where they could be neither seen nor heard.

Infuriated, Croly didn’t attend. But she was intent on doing something about her treatment, and she was well placed to do it. Croly was a well-known reporter who, under the pen name Jenny June, was one of the first American women to write a syndicated column. Later, she became one of the first female journalism professors.

In response to her treatment, Croly founded the first American women’s club, which she named Sorosis: a scientific term for the group of budding flowers that form a fruit. She recruited fellow upper-class professional women, such as the journalist Kate Field and the minister Ella Dietz Clymer. For the first meeting, Croly approached the restaurant proprietor Lorenzo Delmonico. She asked him to host her “risky and outré” group of unaccompanied women for a lunch just two days after the Dickens dinner. Gracious as well as progressive, Delmonico agreed, providing a dining room for the first meeting.

The choice of Delmonico’s was a statement. Not only had Charles Dickens been hosted there (he declined Croly’s invitation to attend the first Sorosis meeting), but Delmonico’s was the culinary center of America. Founded in 1827 as a pastry shop, Delmonico’s became America’s first true restaurant, an island of good taste and good food in a country previously indifferent to fine cuisine. During its mid-century glory years, the kitchen was ruled by French chef Charles Ranhofer, who created dishes such as Lobster Newburg for the politicians, luminaries, and upper crust who frequented Delmonico’s. Croly made the restaurant Sorosis’s headquarters.

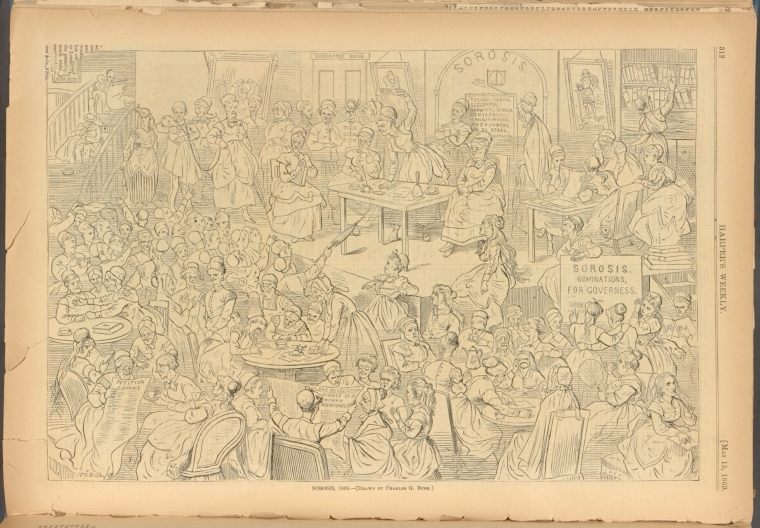

As the first club entirely run and administered by American women, Sorosis immediately attracted attention and censure. The club’s goal was to bring together “women of thought, taste, intelligence, culture, and humanity,” and to encourage women to work. Guest speakers attended regular women’s lunches at Delmonico’s, lecturing on the topics of the day. In January 1869, an editorial in the New York Times poked fun at the development of a charitable coalition between Sorosis and Susan B. Anthony’s “Revolutionists,” which aimed to help the working women of New York. “But the dear creatures are as impractical as ever,” the anonymous journalist wrote about the discussion. Magazines portrayed club members in cartoons as combative shrews. One unflattering 1869 illustration derided both African-American and women’s suffrage, with the caricature of the suffragette holding a knobby club labeled “Sorosis.”

Even under duress, Croly defended Sorosis. “The traditional home life is insufficient for our needs, mental and physical,” she said in 1869. Croly understood this well, since the illness and death of her husband made her the family breadwinner. Croly was a product of her time—she also advised women to be good homemakers and mothers. But she simultaneously worked for 40 years as an author and journalist, and helped found the New York Women’s Press Club and the General Federation of Women’s Clubs.

The club flourished, and by the end of its first year, 83 female historians, writers, artists, and physicians attended its precedent-setting lunches. Before Sorosis’s founding, wrote Lately Thomas in his book Delmonico’s: A Century of Splendor, there had been “no garden clubs, no bridge clubs, no associations for professional women, not even church or missionary societies carried on solely by women.” Sorosis sparked a slew of women’s clubs across America, and many Sorosis branches are still active today. The lunch at Delmonico’s in 1868 kickstarted the emergence of women into the public sphere.

Yet change was slow to come. Certain restaurants and clubs remained off-limits to women well into the 20th century. Two women travelers in 1906 described how a waiter hedged and questioned them until he found out that no man was joining, at which point he refused to let them eat at his establishment. As the 20th century progressed, more and more women worked outside the home and needed places to eat. Yet as late as the 1960s, many restaurants refused to admit women.

While the concept of barring women from restaurants now seems dated, there is once more a national movement of women fighting for the right to pursue careers without harassment. In light of that, as well as the 150-year anniversary of the first meeting of Sorosis, the modern Delmonico’s will offer an updated 19th century menu for a week, starting at a debut lunch on April 20. Under chef and author Gabrielle Hamilton, beef bouillon with Madeira, jellied consommé, soft-shell crab, and brûléed rice pudding will be served. It may very well be what Croly and her recruits ate 150 years ago.

Though the early Sorosis meetings didn’t involve alcohol (the members didn’t want to raise even more eyebrows), Delmonico’s special events director Carin Sarafian thinks the original Sorosis members would want to celebrate the gains that women have made in the last 150 years. “I think they’ll be here in spirit, toasting this remarkable day,” she says.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook