Cracking the Mystery of the Atmosphere’s Dazzling Red and Blue ‘Lightning’

Sprites, elves, and jets look like special effects, but they’re electrical discharges.

In folklore, sprites and elves flit and frolic amid mushrooms and moss. According to astronauts and atmospheric scientists, they also live high up in the sky, too, in the form of mesmerizing weather patterns. With a new tool on the International Space Station, researchers are about to learn a lot more about them.

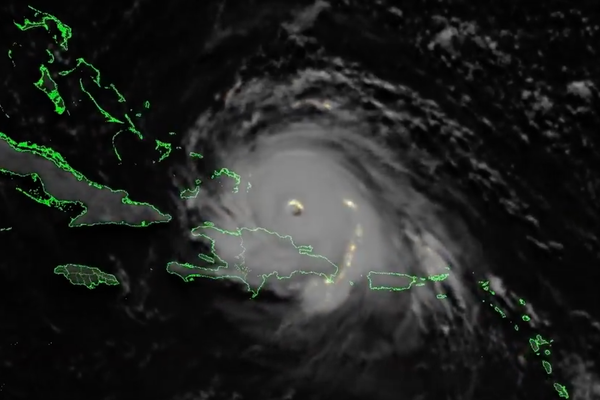

On Earth, we’re used to seeing lightning shooting downward, in the direction of the ground. In the stratosphere, mesosphere, and ionosphere—roughly 31 to 62 miles above storm clouds—sprites and other so-called Transient Luminous Events (TLEs) crack the other way. The dazzling electrical discharges often accompany thunderstorms, but they’re not quite lightning. Blue jets and red sprites spark like fireworks, shooting flares up higher into the darkness, and dangling tentacles beneath them. Elves are electromagnetic pulses that flash horizontally and vanish in milliseconds. (Their name is generally lowercased, but it’s technically a fanciful acronym to shorten “Emissions of Light and Very Low Frequency Perturbations due to Electromagnetic Pulse Sources.”)

Because they manifest so quickly and so far from us, these otherworldly weather entities are uncommon sightings on Earth—not entirely unlike their fantastical counterparts. Pilots reported spotting some throughout the 20th century, but it wasn’t until 1989 that video footage—captured accidentally during a rocket launch—backed up those anecdotes. That prompted NASA to take a closer look at other tapes, where they found a smattering of similar events.

Still, these spectacular bursts have remained somewhat enigmatic. A certain degree of mystery lingers right in their names. The late geophysicist Davis Sentman gave sprites their moniker in 1990s, concluding that they were elusive and fleeting, like those mythical forest dwellers.

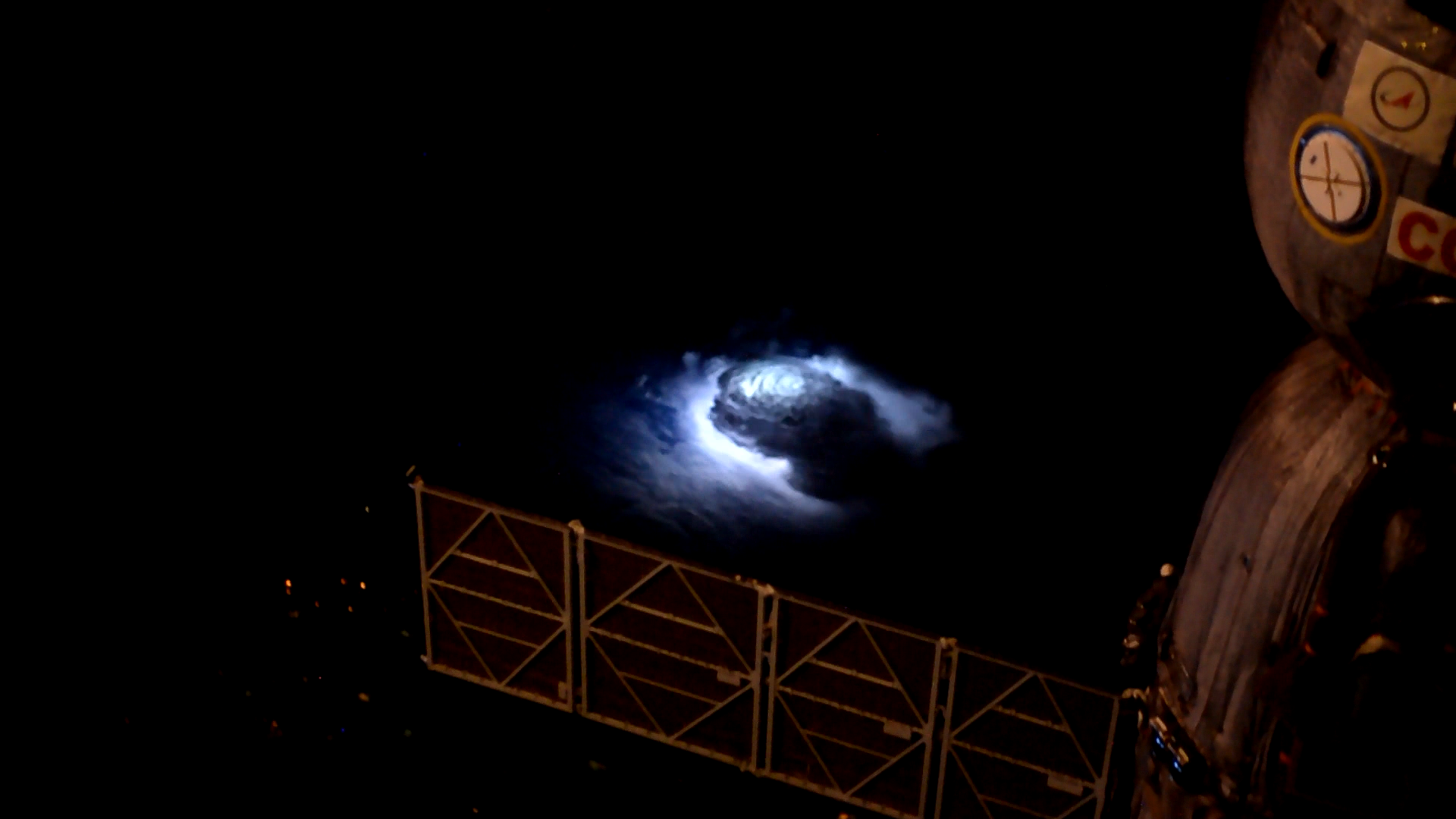

The name has stuck, and many questions have hung on, too. “We don’t know how often these lightning phenomena occur, or under what conditions, or what effect they have on our atmosphere,” said Andreas Mogensen, a European Space Agency astronaut who was sent up on a 2015 mission to document the phenomena. Mogensen’s voyage included a lightning-imaging project christened Thor, after the prickly Norse god of thunder and lightning. Mogensen returned to Earth with beguiling footage of the crackling action.

Now, scientists are hoping for a front-row seat to much more of it. Last week, SpaceX launched a batch of supplies and equipment to the International Space Station—including the Atmosphere-Space Interactions Monitor (ASIM), which will be installed this Friday. When it’s up and running, it will gather data about elves, sprites, jets, and more.

The researchers hope that ASIM’s cameras, sensors, and other instruments will crack open the mystery of the physics and chemistry behind these events. “We don’t really know what’s inside lightning. It happens so fast and it’s so dangerous,” Torsten Neubert, a researcher at the Technical University of Denmark and ASIM’s lead scientist, told the BBC. This project could be a window in, he added—and it’s a landscape with a pretty magical view.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook