The Nazis Tried and Failed to Build the World’s Largest Stadium

The remains of the giant test model are now overgrown on a hillside near Nuremberg.

This week, we’re looking at unfinished infrastructure—places around the world where grand visions didn’t quite live up to their potential. Previously: the nuclear power plant in Crimea that Chernobyl stopped dead, Nikola Tesla’s giant electrical tower, an unfinished highway in Cape Town, South Africa, Cuba’s incomplete National Art Schools.

It was supposed to be the largest stadium ever built. And the Deutsches Stadium would have been a behemoth—almost 875 yards long, almost 500 yards wide and 100 yards tall. It was meant to be hold more than 400,000 people. By capacity, the largest football stadium in the United States today is Michigan Stadium, in Ann Arbor, which can fit around 107,000 spectators.

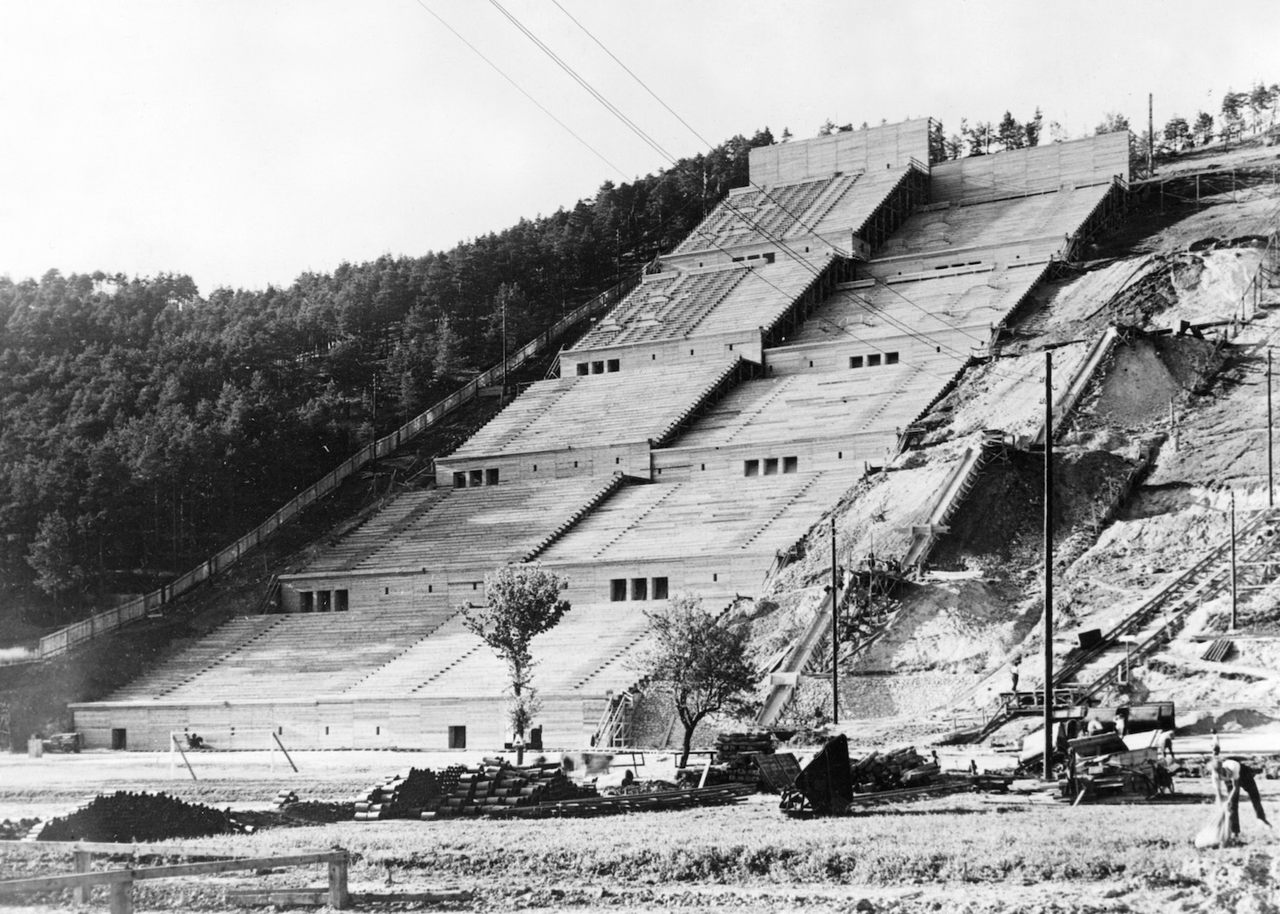

Adolf Hitler’s Nazi regime started working on this extravagant plan in 1937; a cornerstone was laid in Nuremberg, Germany, in 1938. Before the actual stadium was built, though, the Nazi Party’s engineers created a test model, about 25 miles outside of the city, near a small Bavarian village, on a hillside that had the same grade as the planned stadium. Over the course of 18 months, German workers built a stretch of stadium seating that could hold 40,000 people, a tenth of the stadium’s planned capacity.

The giant wall of seating stretched so high up the hillside that a block of people sitting at the top looked like a fuzzy black patch. (The view from the bad seats would not have been much of a view at all, though Albert Speer, the project’s designer, reportedly said that it wasn’t as bad as he imagined.) The workers had poured concrete foundations into the hillside and built the seats out of wood from the surrounding Bavarian forest.

When Hitler came to visit in March 1938, he was happy with results of the test. He imagined that after 1940, every future round of Olympic games would be held in the giant stadium he was building—even though its dimensions didn’t conform to Olympic standards. “That’s totally unimportant,” he said. “It is we who will determine how the sporting field is measured.”

But after the start of World War II, work on the grand stadium and the test model stopped. During the war, Allied troops destroyed much of a nearby village, and the wood from the stadium seating was salvaged to rebuild the town. But the concrete foundations remain, overgrown and ignored, if not forgotten.

In the past couple decades, though, some of the forest that grew over the test model of the unfinished stadium has been cleared away. In 2002, the site was protected as a historic monument. The foundations remain in the ground, concrete reminders of the hubris of Hitler and of his downfall.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook