Don’t Worry, Said Most Weather Reports in Fiji Before One of the Worst Cyclones Ever

How two Peace Corps volunteers narrowly escaped Cyclone Winston–an option that few Fijians had.

Cyclone Winston damage in Tailevu, Fiji. (Photo: Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade/CC BY 2.0)

Cyclone Winston damage in Tailevu, Fiji. (Photo: Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade/CC BY 2.0)

When Peace Corps volunteer Carissa Wills-DeMello arrived at the grass-strip airport in Koro, Fiji, on Saturday, February 20, the winds were picking up. She watched the eight-seater plane emerge from a mass of gray clouds, then turn around and disappear. Minutes later, it reemerged, then turned around a second time.

A Fijian police attendant at the airport shook his head, and they were just about to load back into the truck to leave, when the plane reappeared again, this time finally landing. “If it had come 30 minutes later, I don’t think we would have gotten off the island,” says Wills-DeMello, speaking from a hotel in Suva, Fiji’s capital.

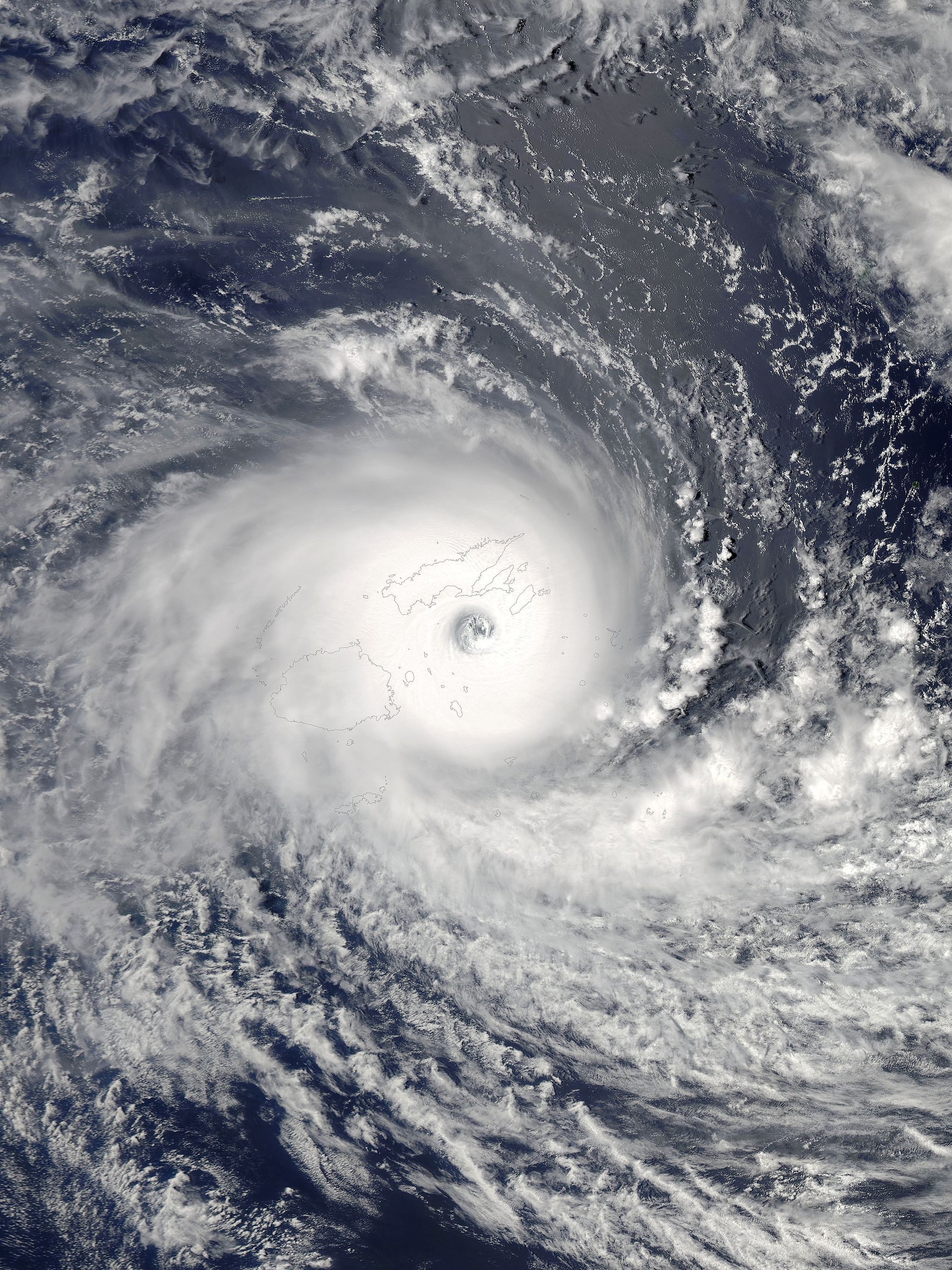

On February 20, Fiji—a nation composed of over 330 islands located in the South Pacific Ocean—was hit by a Category 5 cyclone; it was the strongest storm ever measured in the Southern Hemisphere and one of the strongest the Earth has ever seen. The previous month, January 2016, was the planet’s most abnormally warm month since humans began keeping records in 1880, and elevated ocean temperatures fed directly into the cyclone’s intensity.

Cyclone Winston descending upon the islands of Fiji on February 20. (Photo: NASA/Public Domain)

But Cyclone Winston was unique in its extreme unpredictability. Leading up to the storm, forecasts fluctuated daily, and often dramatically; many locals laughed off the changing reports. “There’s a big pervading myth on Koro and all of Fiji,” says Wills-DeMello, “that storms don’t come here.”

Wills-DeMello, a 2013 college graduate, was in the second year of her post in a village of about 200 people on Koro, an island with 14 villages, around 3,500 inhabitants, and one dirt road. Like most of Fiji, Koro functioned on a subsistence economy of fishing and farming, the main crops being dalo (taro), cassava, and kava. Few people have electricity, and while mobile phones are common, only teachers have computers.

Most Fijian communities rely of farming and fishing. This is Wills-DeMello’s “na” (mother) getting fishing bait ready. (Photo: Carissa Wills-DeMello)

In the week leading up to the cyclone, villagers got whichever weather reports crackled through on the radio. After a few unthreatening reports, everyone assumed that Koro was in the clear. When the Peace Corps suddenly called the day before the storm, and told Wills-DeMello to leave immediately, she grabbed just a few basics. “It never crossed my mind that my house would be blown away,” she says.

It wasn’t until Saturday, the morning of the storm, that anyone in Wills-DeMello’s village began to make serious preparations to secure their houses and belongings. The shift came when relatives in the cities started calling to warn family members on smaller islands like Koro, that the storm they’d all been hearing about might be a bigger deal than anyone had imagined.

Carissa Wills-DeMello with her Fijian family in Koro. She doesn’t know if and when she’ll be able to go back to see them. (Photo: Carissa Wills-DeMello)

Carissa Wills-DeMello with her Fijian family in Koro. She doesn’t know if and when she’ll be able to go back to see them. (Photo: Carissa Wills-DeMello)

For Connor MacKenzie, a first-year volunteer on the outer island of Kadavu, circumstances leading up to the storm were flipped. MacKenzie had a bag packed all week long in case he was told to get out. On Thursday, the storm did a U-turn from nearby Tonga, a country to Fiji’s east, and then lined up directly for Fiji. At that point, it was only a Category 3, and no one in MacKenzie’s village was worried. But overnight, it grew into a Category 4, and Kadavu was projected to be right in the eye of the storm.

At 2:30 p.m. on Friday, he received a call from his program manager: “How fast right now could you get to the airport? You need to get there within an hour.”

Hanging on the beach on the island of Kandavu before the storm. Kandavu, unlike most of Fiji, was left generally unharmed. (Photo: Connor MacKenzie)

MacKenzie grabbed the bag he’d prepared and jumped into one of the fiberglass boats that transport people around (the island has no roads). When he arrived at the airstrip, he found that the plane hadn’t made it, since the sky was too dark and the plane didn’t have lights. On Saturday morning, MacKenzie and one other volunteer climbed inside a little prop plane and made the 40-minute flight to Suva. There, in the capital, MacKenzie, Wills-DeMello, and other volunteers waited out the storm in a concrete building equipped with generators, food, and water.

“When I left my house,” says MacKenzie, “I was thinking, ‘Well, I think this is the last time I see my house, the last time I see my village. Goodbye everybody; please stay safe.’”

MacKenzie and Wills-DeMello both recognize not only their luck in escaping, but also their privilege. As members of the Peace Corps, they had support and resources that their Fijian neighbors and family members lacked. Local Fijians didn’t have an outside organization to monitor their safety, or the option of evacuation. Their islands are hard to access even when conditions are perfect, not to mention on the eve of a storm.

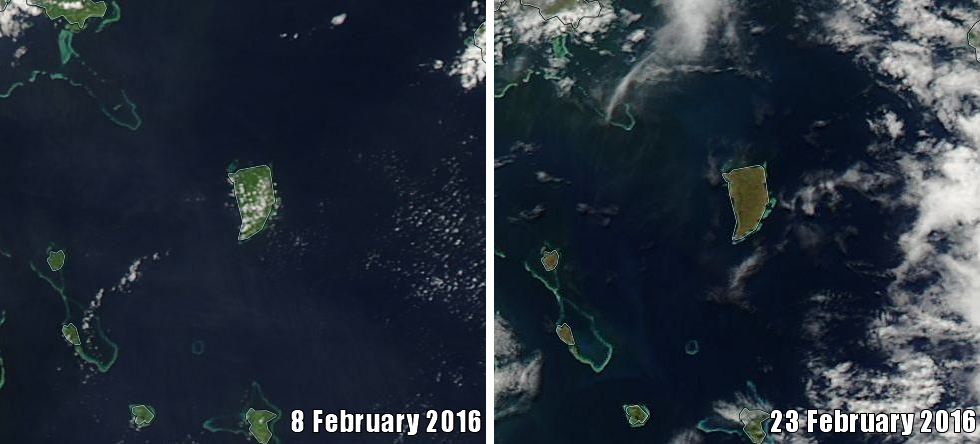

Cyclone Winston demolished plant life on the islands. You can see the change here from green to brown. (Photo: NASA/Public Domain)

The wrath of Winston skirted MacKenzie’s community, but that was a lucky exception. “The rest of this country is absolutely destroyed,” he says. Other islands were flattened; in some villages of 150 houses, the only structures still standing are the churches. Everything else was blown over, and then the sea came and washed it away.

Wills-DeMello has spent every day since arriving in Suva trying to get in touch with anyone in her village by telephone. For a long time, there was nothing. It was frightening and exhausting, she says. She and Luigi, another Koro volunteer, tried calling their district officer over and over.

Finally, he picked up his phone. He had walked seven hours from Koro’s capital to another village, just trying to find cell service. The island was completely in the dark, he reported. This was the first time anyone had connected to the mainland.

Meanwhile, the number of reported deaths was steadily rising as support efforts began arriving to the affected islands. The first relief efforts, from nations like Australia, India, and New Zealand, brought in food, water, and temporary shelters. But stagnant water and mosquitoes began breeding concerns over typhoid and Zika outbreaks.

“It’s going to be a long process, but it could be more successful if more people are involved in thinking creatively about how Fiji can respond, instead of just dropping off a stack of corrugated iron,” says Wills-DeMello, who believes there needs to be a focus on developing new, better infrastructure, constructing stronger homes, and planting disaster-resistant crops. “Just because money is being sent doesn’t mean we’re getting what we need.”

Humanitarian supplies headed to Koro. (Photo: Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade/CC BY 2.0)

No one can predict when kids will be back in school or cell phone towers resurrected. Wills-DeMello thinks it might take at least a decade before Koro can fully recover. But both she and MacKenzie report that Fijians are accepting their misfortunes with equanimity.

“Fijians have this zen perspective on life—that life unfolds the way it’s supposed to unfold, and they don’t really get stuck on mourning or obsessing over how they think things should happen,” Wills-DeMello explains. “People who’ve lost their homes and lost their family members can just say, well, the storm came, all we can really do is move on.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook