Revisiting Dyckman Oval, A Lost Landmark From the Heyday of Black Baseball

At the northern tip of Manhattan, the ballpark was a magnet for families, entrepreneurs, and celebrities.

On a recent weekday morning, I took the I.R.T. to Inwood in northern Manhattan, where from 1915 to 1938 the ballpark Dyckman Oval was a frequent backdrop for Black baseball players barred from the Major Leagues. My train arrived at the Dyckman Street elevated station and I descended to the street. Encountering few other pedestrians, I walked uptown along broad, windswept Nagle Avenue. I soon reached where Academy Street hits the avenue; Academy used to cross the area, creating a natural placement for Dyckman Oval’s home plate and a parallel for the first base line. It was easy to envision a baseball park in that space, the third base line bordering Nagle with the El looming overhead, 204th Street out beyond left field and Amsterdam Avenue past right.

Dyckman Oval was just 50 blocks north of the Polo Grounds, where, 100 years ago, the World Series was held entirely in New York City for the first time. But while the Giants and Yankees faced off, Black teams were at Dyckman and all over the city. (I am setting aside the term “Negro Leagues” so as to include all the games played by Black teams, not just those considered part of league play.) They played at small stadiums and neighborhood parks such as Dexter Park, Ivanhoe Park, and Recreation Field in Queens; Catholic Protectory Oval and Bronx Oval in the Bronx; and New Lots Oval and Suburban Oval in Brooklyn. In prior years, the list would have included places such as Harlem Oval, Olympia, and Olympic Fields in Harlem, and Wallace’s Ridgewood Grounds in Queens.

One former Negro Leaguer, Pedro Sierra, welcomes attention to these sites. Black Baseball, he says, constitutes “an important chapter in baseball history” because the sport “isn’t meant for just one skin color.” Sierra, born in 1938, grew up in Cuba idolizing Negro League players, and started playing professionally long after the parks of 1921 were gone. When his career ended, he participated in exhibition games in Central Park celebrating Negro League history, but he was unaware of its past local locations. To uncover these sites, says native New Yorker Rowan Ricardo Phillips, an author and poet who is writing a book about Black baseball, is to remember “what happened and what was, what lived and thrived in places where we walk by today”—a history hidden in our midst.

Dyckman Oval’s history includes famous boxing and soccer competitions, but soon after its 1915 opening it became associated with Black baseball. In 1918 it was the frequent home of the short-lived New York Red Caps, and in 1919, the Bacharach Giants of Atlantic City began scheduling games there, largely due to the involvement of new owners John Connor, owner of the Royal Café and Palm Garden in Brooklyn, and Barron D. Wilkins, who ran clubs such as the Little Savoy on 35th Street and Barron’s on 134th. At the time, the Bacharachs were the only local team with Black ownership, according to Ted Hooks, sportswriter for Black weekly The New York Age. Starting in the mid-1920s, Dyckman served as home of numerous Negro League teams, including the Black Yankees, the Cuban All-Stars, and the New York Cubans. The latter two teams were owned by Alex Pompez, who was hugely influential in developing the business of Black baseball.

Dyckman, in these early years of the Harlem Renaissance, according to Rory Costello of the Society for American Baseball Research, “was a convenient location for Harlem’s sizable black population, well served by public transportation, and northern Manhattan had also become home to a large number of baseball-loving Latinos.” He added: “Celebrities such as Joe Louis, track star Jesse Owens, and jazz pianist Fats Waller were often in the crowd, which impressed even the ballplayers.” Costello cites historian Adrian Burgos Jr.’s description of the Oval as “a unique cultural space… The ‘color’ and ‘spirit’ of the scene produced a sense of collectivity, pride, and affirmation.” As early as 1920, jazz bands entertained the crowds at Dyckman games.

The city demolished the park in 1938. Currently, nestled in the former left field corner is Monsieur Kett Playground, while what was once the infield is given to the Dyckman Cornerstone Community Center and basketball courts that host high-profile amateur tournaments, often featuring cameos by NBA stars. Grandstands sit where third basemen and shortstops once fielded grounders. The Dyckman Houses, a massive housing project, has occupied the southwestern portion of the expanse, adjacent to the park, since 1951.

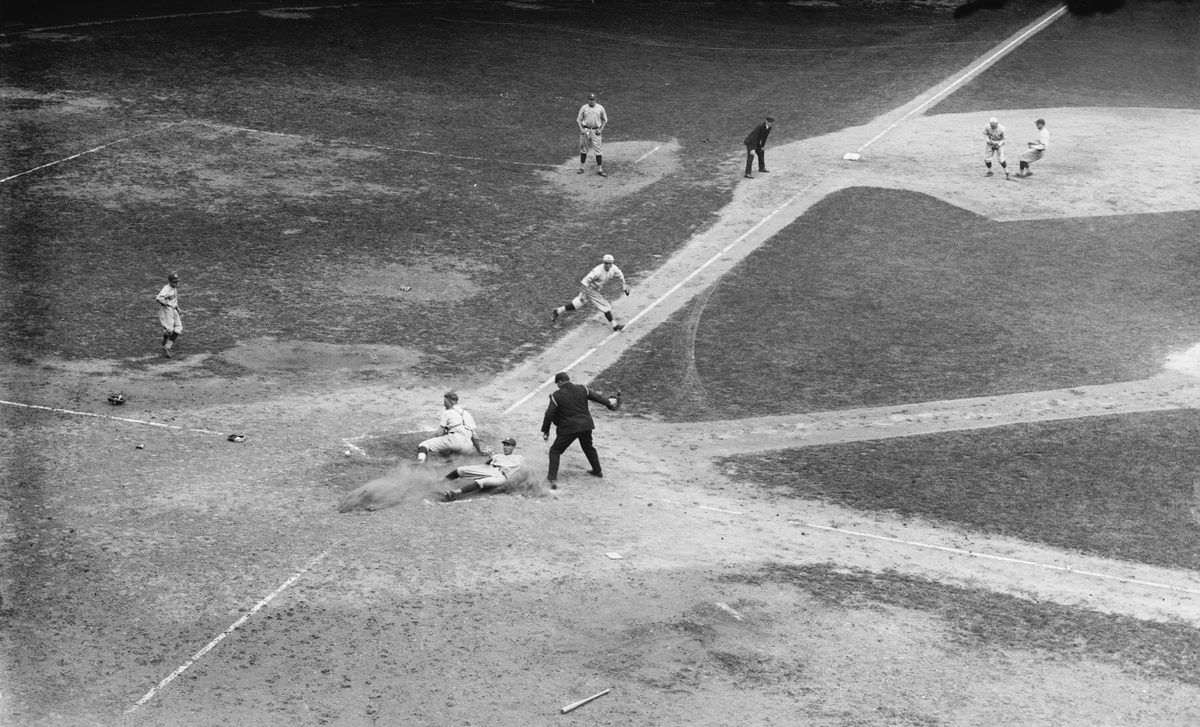

On my visit, I stopped to observe an informal 3-on-3, watching through the chain-link fence that rings the court. I started imagining what the scene looked like on October 2nd, 1921, when the Bacharachs played a doubleheader against the Chicago American Giants. The Americans, run by Rube Foster, founder of the Negro National League, were champions of the NNL with a 41-21 record, and a big draw: Dyckman’s largest crowd of the season turned out on what was also the last day of the Major League season. In my mind I saw crowds of Black fans arriving at the same I.R.T. station I had, walking en masse to the park, filling the grandstand that held up to 10,000 people. (Accounts of its capacity vary.)

Superimposed over the basketball game before me, I pictured Julio Rojo, the Bacharachs’ Cuban catcher, squatting behind home plate, and future Hall of Fame pitcher Dick Redding, the Bacharachs’ player/manager, striding out to a spot 60 feet, six inches away and then throwing Rojo his warm-up pitches. I tried to summon up the noises of the park, what Phillips calls “the long lost sounds we’re in search of today.” I played early jazz in my head. I heard raucous cheers, then the slow swell of groans: Redding gave up three runs in the first game while the Bacharachs scored once, on Rojo’s home run, as the Americans “completely outclassed” the locals (so said the New York Age). I imagined the second game starting under a somber autumn sky with the sun setting behind the elevated tracks; it was called a tie as darkness engulfed the park. I saw the crowd thin and then stream back to the streets.

The basketball game played on. A fellow observer glanced my way, so I took the opportunity to ask whether he had ever heard of the ballpark there. He had not. When I asked whether he lived nearby, he gestured toward the Dyckman Houses. As a current resident of the area, he has no reference, no marker to inform him of the Dyckman Oval; the city provides no history of itself.

“Black baseball and the history of New York City are both charged with a type of deep layering that asks us to dig below the surface of what we see in the present,” says Phillips. “Both demand we engage in a certain type of urban excavation to make sense of a rather ethical reading of a palimpsest.” I honored that demand, gripping the chain-link fence that kept me outside the basketball court while allowing me to witness the present moment, an unrecorded game.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook