In 1933, Four Cows Went to Antarctica

It was not their idea.

Guests of New York City’s Commodore Hotel in the 1930s were used to spotting celebrities. But on May 15, 1935, they were joined by two true heavyweights. Around lunchtime, a cow and a bull were wheeled out of a freight elevator and into the East Ballroom, where they mingled with guests and posed for photos. “Both had hay cocktails—heaps of hay with cracked ice,” explained the New York Times, which covered the event. Despite this delicacy, they grew restless: “Iceberg [the bull]… grunted vociferously,” the Times reported. “Foremost Southern Girl [was] also indifferent to the speeches.”

No one likes to be ignored, even by a cow. But the speakers and the hay-bartenders were likely sympathetic. These two animals, more than most, were used to adventure: Just days before, they had returned from a two-year trip to Antarctica, where they and a couple of other cows had been part of an expedition led by Rear Admiral Richard E. Byrd.

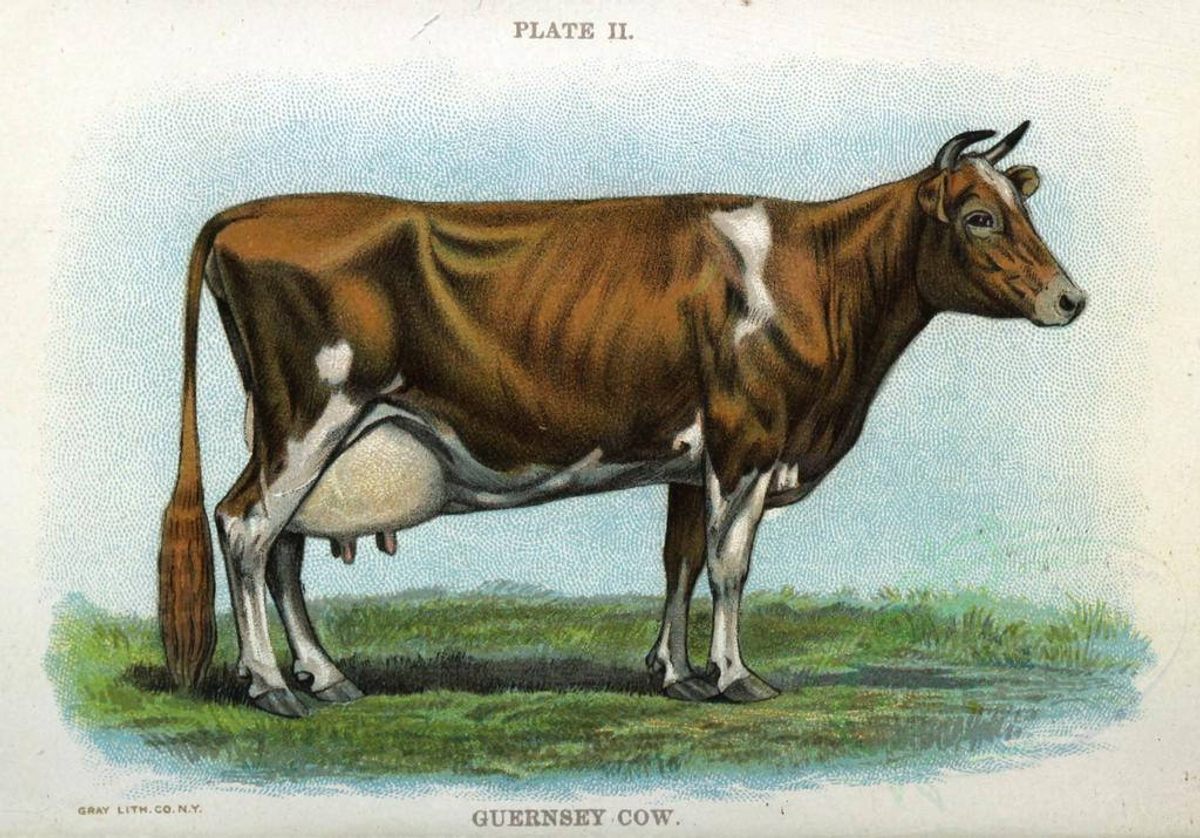

What drives someone to bring cows to the bottom of the world? In the press, Byrd gave one main reason: milk. “Admiral Byrd drinks two quarts of Guernsey milk daily,” one article explained. Another said that although Byrd had brought plenty of dried and evaporated milk on his first expedition to the continent, the crew missed the real thing.

But as Antarctic scholars Elizabeth Leane and Hanne E.F. Nielsen detail in a recent paper, Byrd likely had other motives, too. One was publicity: While Byrd initially gained fame for his feats of derring-do—becoming the first person to fly over the South Pole, for example—this expedition was a bit more staid. It focused on scientific endeavors, including meteor-spotting and ice-cap-measuring, rather than dramatic stunts. “[The cows] added some novelty and newsworthiness to an expedition which, in contrast to Byrd’s first Antarctic venture, threatened to be a little dull,” Leane and Nielsen write. More news coverage meant more sponsorships, and more chances to raise money in the future.

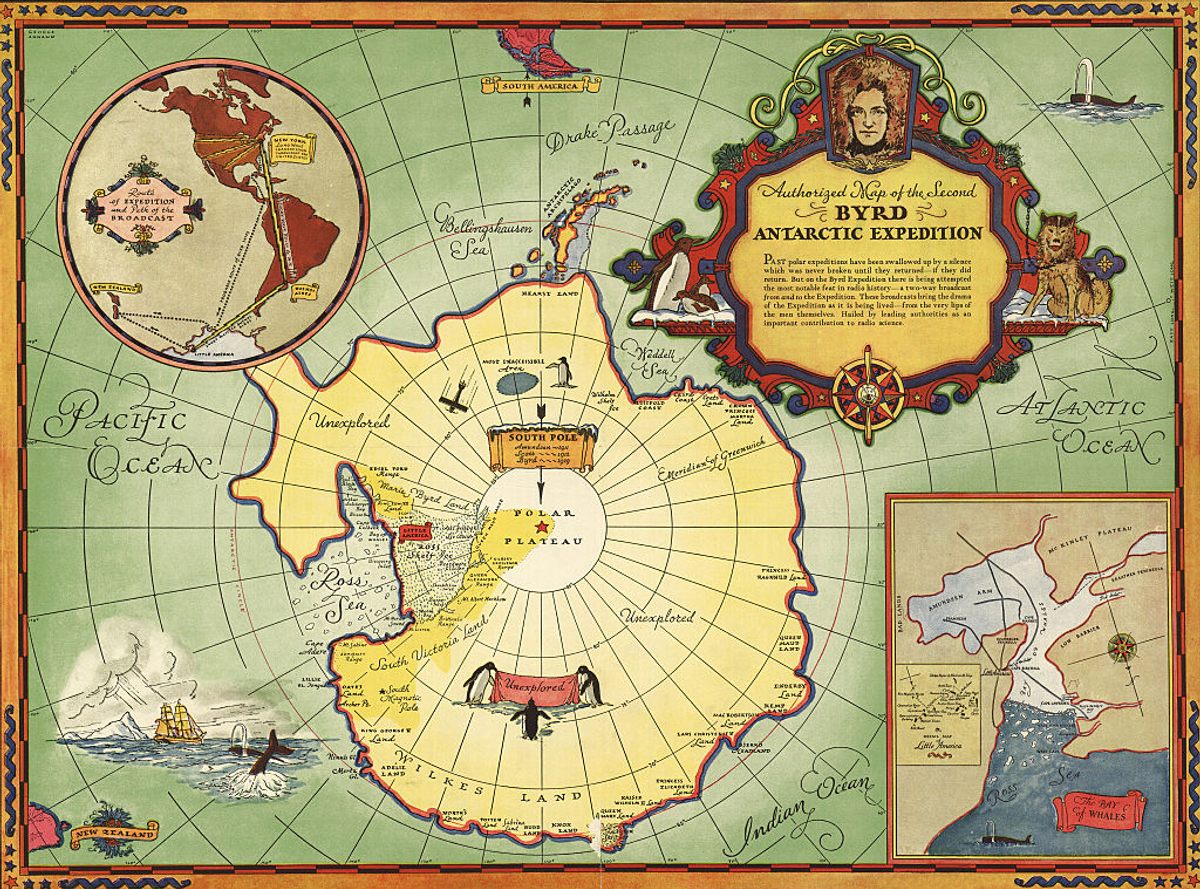

Another impetus, they argue, was more symbolic. Over the course of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as other countries scrapped for territory at the bottom of the world, the United States had fallen a bit behind. By the time the 1920s and ’30s came around, nations including France, Argentina and Great Britain had claimed chunks of the continent, and America found itself at a bit of a geographic disadvantage: even the base Byrd had established during his first trip was on land the British considered their own. To that end, Leane and Nieslen write, Byrd had purposefully styled said base “in the form of a frontier town,” calling back to the the U.S.’s colonial-era pushes into (supposedly) unknown territory. He called it “Little America.” And what was a little America without a little dairy farm?

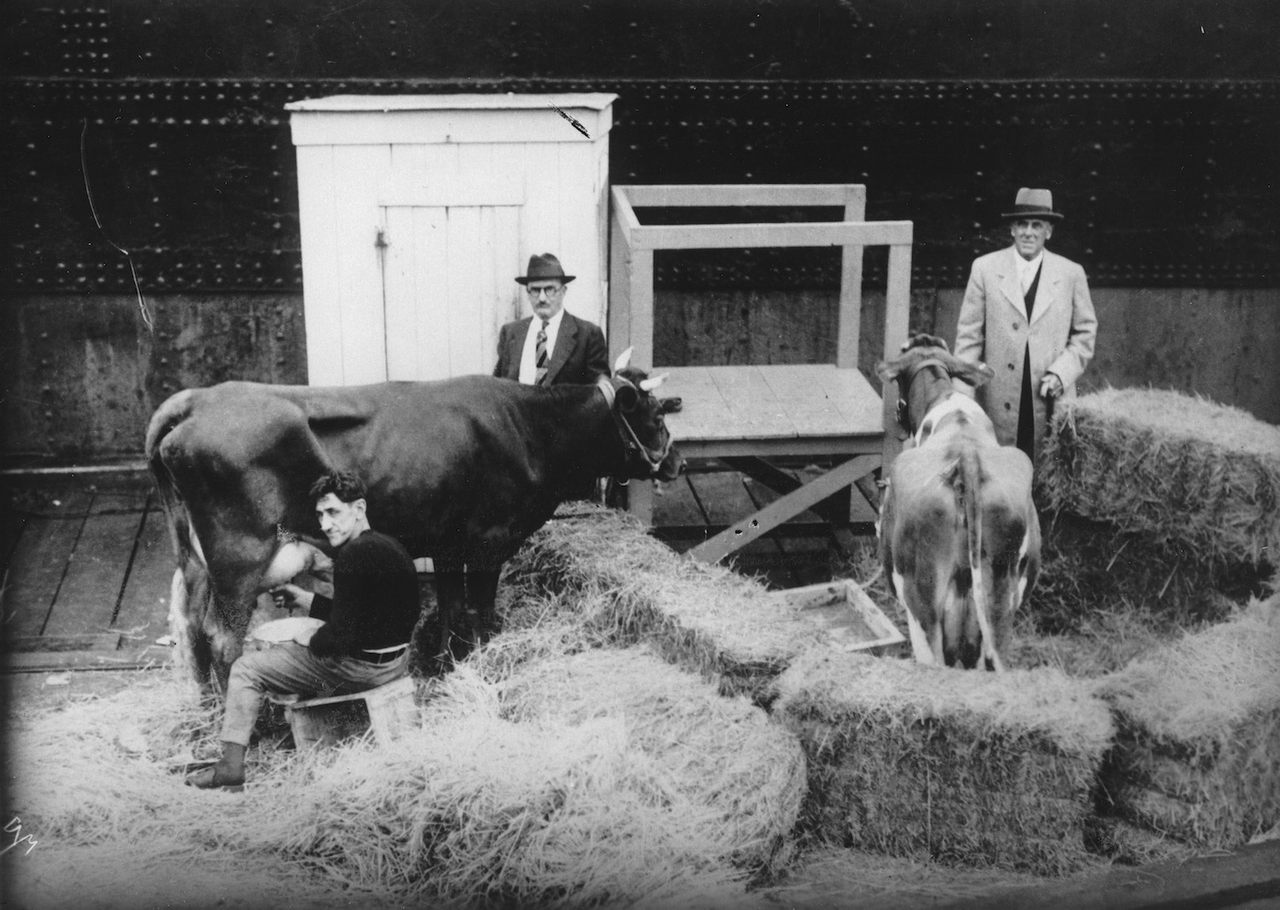

And so—for all these reasons, and perhaps more—in the fall of 1933, the team loaded a trio of Guernsey cows into the SS Jacob Ruppert. There was “Foremost Southern Girl,” from New York, “Deerfoot Guernsey Maid,” from Massachusetts, and “Klondike Gay Nira,” from North Carolina, who was pregnant. All were the same breed, thanks to a deal Byrd had struck up with the American Guernsey Cattle Club. The crew’s carpenter, Edward Cox, shouldered the caretaking responsibilities. A bevy of other sponsors provided the cows with some necessary accoutrements: 10 tons of feed, various farm equipment, and a Surge Milking Machine.

The cows took the three-month journey alongside their human companions, living first in a knocked-together stall on the deck, and later, after it was completed, in a larger barn below. There was hope that Klondike would give birth within the Antarctic Circle, giving her calf “a unique claim to immortality,” as Byrd put it in his memoir of the expedition. Instead, it happened about 250 miles too far north. Still, this proved more thrilling than the frozen surrounds: “Almost to a man the crew waited with breathless expectancy for an event which has been common in Nature since the world began,” Byrd recalled wryly. They named the calf Iceberg—only fair, given baby icebergs are called calves—and the birth announcement made the New York Times.

The team made landfall in mid-January, and soon after, the cows were craned down from the ship and onto the ice. Southern Girl immediately tried to walk back up the gangplank. According to a crew dispatch, Iceberg “took it like a major and led the way,” trekking three miles on foot before hitching the rest of the way in a tractor. A wood-and-iceblock cow barn went up in Little America, alongside other new infrastructure—including a mess hall, a meteor observatory, and an underground “dog town” for the expedition’s 126 huskies—and the four cows moved in, along with Cox and his assistant, the milking equipment, two kittens, and a wolf-dog hybrid named Jimmy.

It was a pretty strange life for a cow. “The only relaxation they have is a weekly walk down the narrow tunnels during which they are usually assaulted by the wild pups from dogtown, and the only grass they have seen is hay at least a year old,” the crew’s head of communications, Charles J. V. Murphy, said in a radio dispatch. “In spite of it all they maintain that blank, docile expression of resignation characteristic of all cows.” It helped that they were pampered by the crew members, who liked to visit the warm, lively barn. “If our cows get back to New York alive they will be worth 20,000 dollars,” wrote one fan. “Don’t we all make a fuss of them … they love apples.”

Caring for the cows could be tough work. “To me one of the most melancholy sights of the winter was the spectacle of Cox, with the temperature -70°, trying to pry with a crow bar a bale of hay from a stalagmite of ice,” wrote Byrd. It didn’t always pay off, either: although the three adult cows gave “up to 40 quarts of milk a day” at first, this later slowed to “a trickle which barely moistened the morning cereal.” In mid-December, Klondike—who had suffered a bad case of frostbite—was put down via gunshot, while a weepy Cox covered Southern Girl’s ears. Meanwhile, despite the crew’s wishes, Iceberg steadfastly refused to mate with Deerfoot. Three cows had left for Antarctica, and only three cows would return.

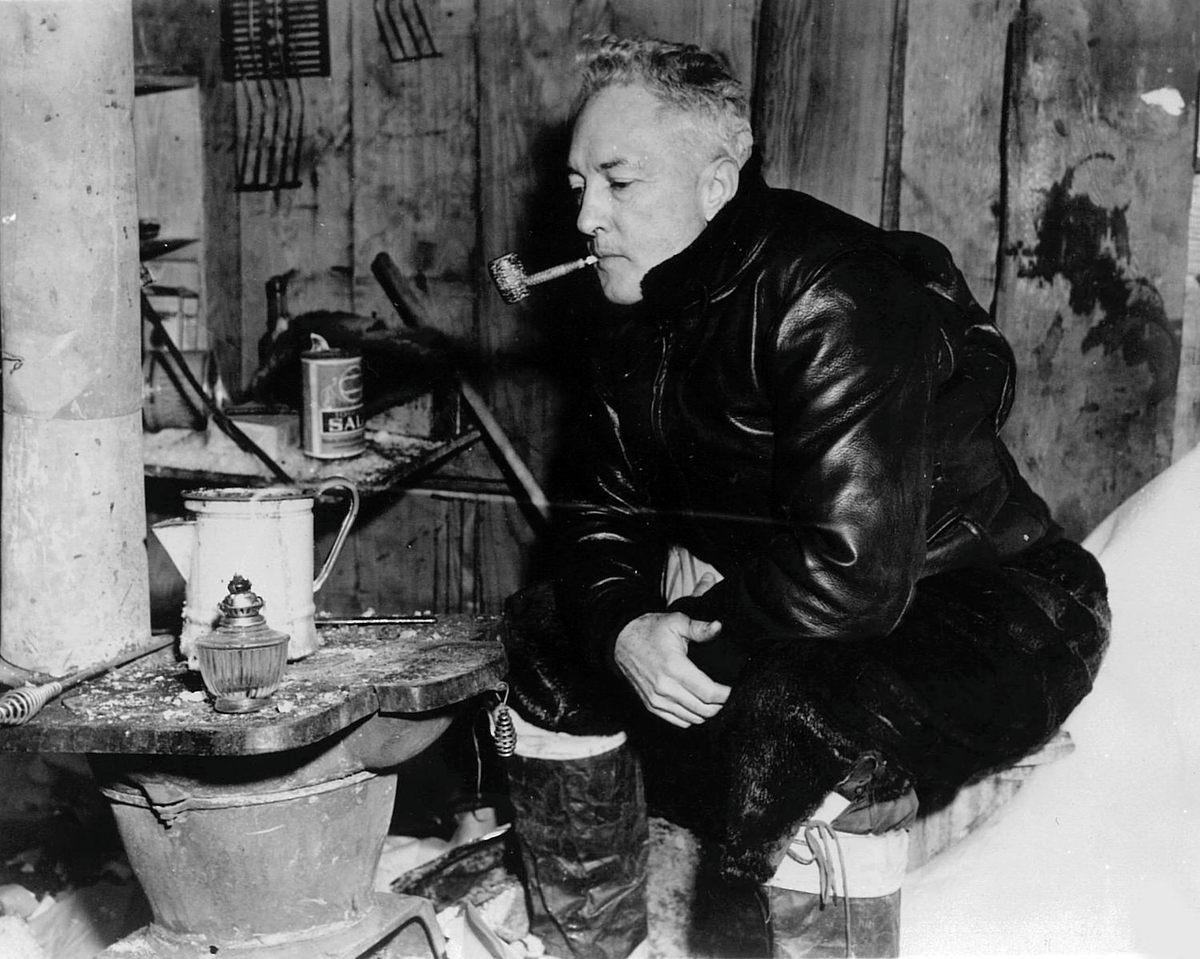

Meanwhile, back in the U.S., various bureaus and companies were happily capitalizing on the cows’ journey. Larro Dairy Feed, which provided rations for the cattle, put out a multi-page booklet about “the first cows to ever venture into the frozen wastes of the South Pole region.” Several New York newspapers reported on how happy the state’s Commissioner of Agriculture was to receive good tidings from “the strangest dairy in the world.” When Admiral Byrd returned to the base from an ill-fated solo journey, Leane and Nielsen write, the Guernsey Breeders Journal published an article detailing his calcium-rich recovery, titled “The Milk Really Pulled Me Out Of My Tailspin.”

In early 1935, Deerfoot Guernsey Maid, Foremost Southern Girl, and Iceberg got back on the Jacob Ruppert, which arrived in the U.S. that May. Although the expedition was over, all three were on the hook for a different kind of journey: a publicity tour.

Iceberg and Southern Girl made their appearance at the Commodore. Deerfoot—who never lost the shaggy winter coat she grew during the trip—showed up at the Michigan Dairy Fair, at which point she had already “grazed on Boston Common … eaten from a banquet table in one of Washington’s best hotels, [and] crooned over the radio.” Even after all three retired to their original farms, their legend spread via screenings of a documentary called Guernseys Discover Antarctica, which apparently features footage of Iceberg “frisking on the ice barrier… at the tender age of two months.”

Byrd returned to the Antarctic multiple times, and eventually helped establish the current American base, McMurdo Station. He never brought cows with him again, and, it seems, neither did anyone else. As for Iceberg, Deerfoot, and Southern Girl, their expressions continued to betray very little. As dispatcher Murphy put it during the expedition, “it is a great pity that cows can’t talk. I would certainly like to hear what they think of this whole business.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook