For Teddy Roosevelt’s Son, Rebelling Meant Sneaking Christmas Trees Into the White House

President Roosevelt thought trees should stay outdoors—so in 1902, his son took matters into his own hands.

Theodore Roosevelt was tough. As a deputy sheriff on the Western Front, he chased a trio of boat thieves down a flooding river for eleven days. Once, when a gun-toting cowboy made fun of his glasses, he beat him up bare-handed. Another time, he got shot in the chest while giving a speech, and just kept on talking.

But on December 25th, 1902, one man got the better of Roosevelt—his eight-year-old son, Archie. And he did it all for the sake of a Christmas tree.

These days, a tree is a vital part of any Christmas tableau. But back in the mid and late 1800s, that particular tradition hadn’t quite taken root, Jamie Lewis explains on Forest History Society blog. While households with small children might put one up, others still considered the trees too pagan, too German, or just too difficult.

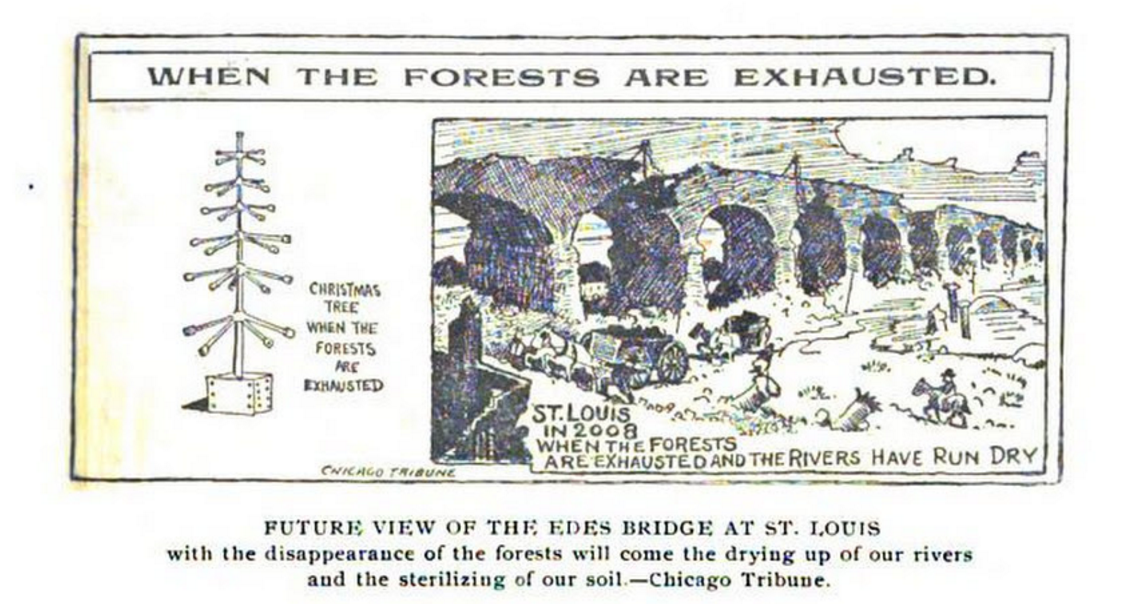

Starting at the turn of the century, Christmas trees also also faced an environmentally-minded backlash. In an editorial, the Minneapolis Times warned that the annual harvest “threatens to strip our forests;” soon after, the Hartford Courant bemoaned what they called “an altogether endless sacrifice… just to meet the calls of an absurd fad.”

The public agreed: “Many among the general public opposed cutting trees for the holiday because of the injurious impact on forests, the destructive methods used to harvest them, or the overall perceived wastefulness of the practice,” writes Lewis.

In 1899, one green-minded group took their grievance all the way to the White House, sending letters calling on President McKinley to publicly denounce the “Christmas Tree Habit.” (While McKinley, childless by the time he took office, didn’t put up a tree for himself, he was known to keep one around for the White House maids.)

There’s no evidence that this lobby also reached out to Roosevelt, who became President in 1901, after McKinley’s assassination. As it turned out, though, they didn’t have to—Teddy and his wife, Edith, just weren’t that into Christmas trees.

It’s unclear what put the Roosevelts, who had six young children, off the custom. Although Teddy was a staunch environmentalist, he never specifically spoke out against harvesting Christmas trees—and Gifford Pinchot, whom he eventually chose to head up the U.S. Forest Service, was in favor of the practice. The true naysayer may have been Edith, who, Lewis postulates, probably had enough to deal with: “They’ve got a bunch of rambunctious kids, and this growing menagerie of animals as well,” he says.

In years past, they had sated their kids’ arboreal appetites by going to see the tree at the local Episcopal Sunday School, or at the home of Theodore’s sister, Anna Cowles, who always had a big one. But by 1902, dissent was quietly growing in the ranks. While the New York Sun reported early that “there will be no Christmas tree at the White House,” Archie Roosevelt, the family’s next-to-youngest child, was secretly taking matters into his own hands.

That year, the Roosevelt parents had arranged a tasteful Christmas for their brood. A December 26th letter from the President to James Garfield (whom he addressed as “Jimmikins”), sets the scene: bulging stockings, dancing in the East Room, and an electric train set for the children, rigged up by the White House electrician.

“But first there was a surprise for me,” writes Roosevelt, “for Archie had a little Christmas tree of his own which he had rigged up with the help of one of the carpenters in a big closet.”

According to Robert Lincoln O’Brien, then Washington correspondent for the Boston Transcript and a close friend of Roosevelt, this event was weeks in the making. A steward had smuggled a two-foot-tall fir top into the White House at the request of Archie, who had hidden it in one of the many unused clothes closets and slowly trussed it up.

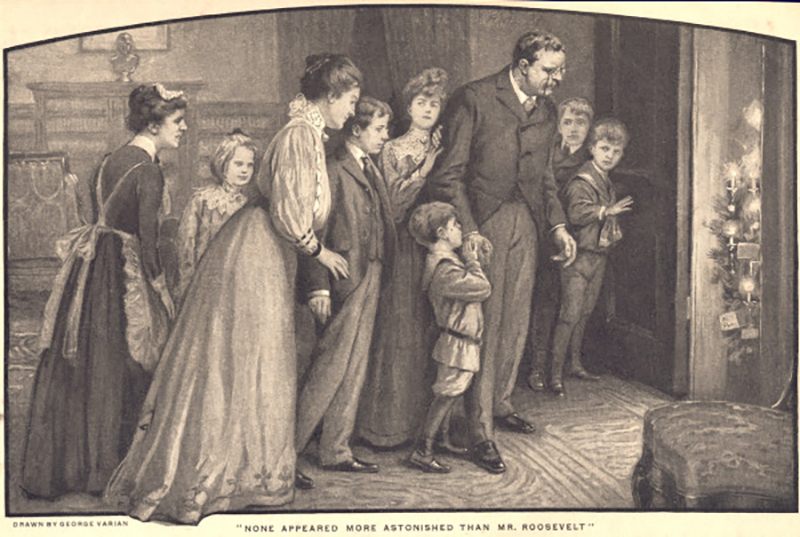

The eight-year-old then gathered everyone around for the big reveal. “All the family were there… but none appeared more astonished than Mr. Roosevelt himself at the sight of this diminutive Christmas tree,” O’Brien wrote in a 1903 account, published in Ladies’ Home Journal.

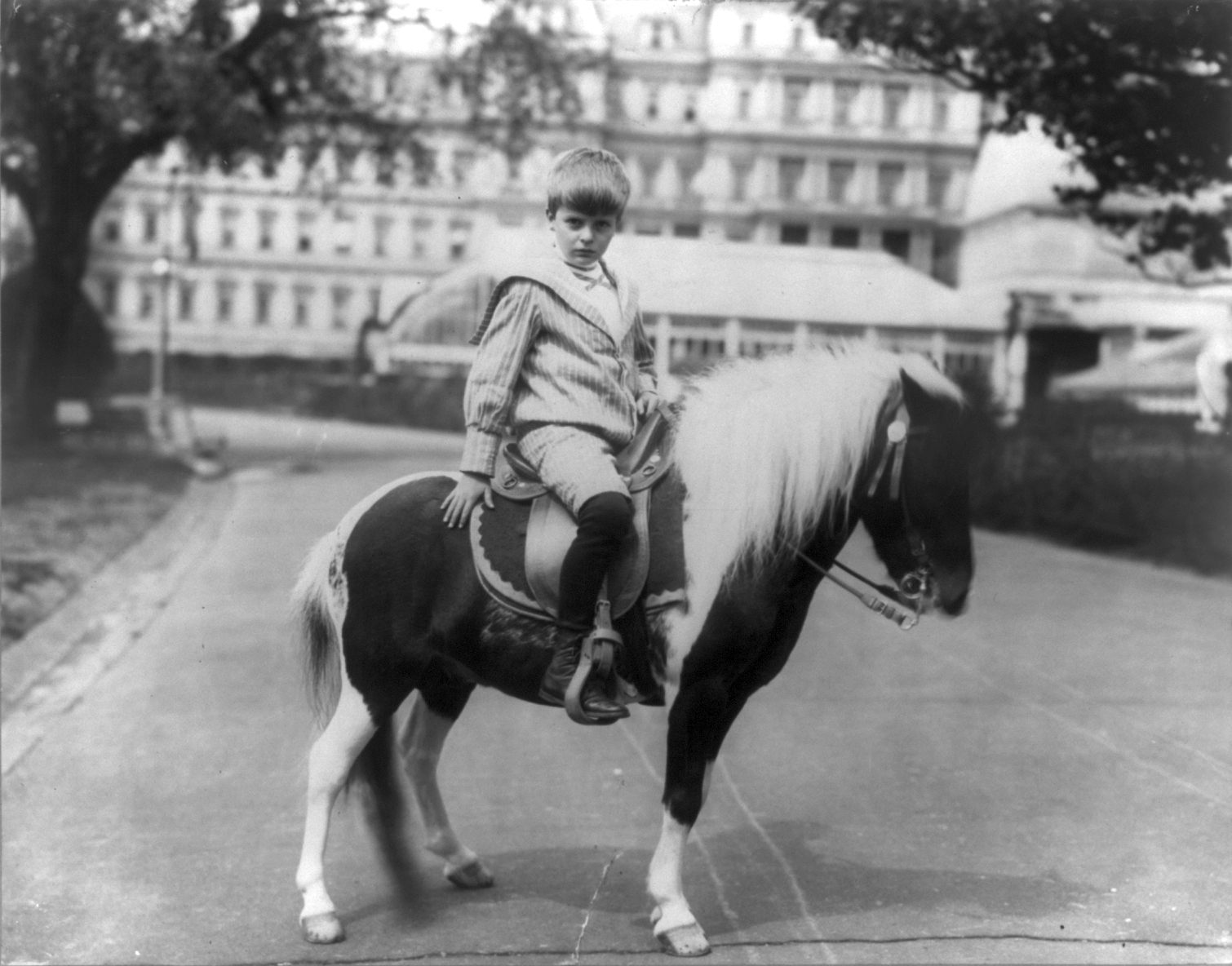

“We all had to look at the tree,” Roosevelt continues, “and each of us got a present off of it. There was also one present each for Jack the dog, Tom Quartz the kitten, and Algonquin the pony.”

Roosevelt offered no further reaction to the tree, choosing instead to talk about his own chosen Christmas pursuits (a three-hour horse ride and several games of cudgels). Letters from later years indicate that Archie turned his triumph into a new tradition. In 1906, there were apparently two secret trees—Archie’s closet tree, and a second made especially for their parents. By 1907, in a note to his sister, Roosevelt tosses off a cool “There was a Christmas tree of Archie’s” as though it were old hat.

The press, though, couldn’t get enough of the story. After O’Brien’s version was published, every holiday season saw papers from coast to coast speculating as to whether Archie would pull his trick again. In 1904, the Washington Times reported a spat between Archie and his baby brother, Quentin: “This year [Archie] announced that he was ‘too big for kids’ things,’ but offered to fix up a tree for Quentin,” the Times wrote. “His younger brother, however, spurned this offer, informing Archie that if he wanted a tree he could make one for himself.”

Like Washington’s cherry tree chop, Archie’s plant exploits eventually took on a life of their own. At least one writer has credited Archie as the first person to bring a Christmas tree into the White House. (That honor, though disputed, probably belongs to Franklin Pierce.) Others held that Theodore had been swayed by the anti-tree lobby, with some spinning elaborate yarns in which Archie and Quentin called on chief forester Pinchot, begging him to talk the Grinchiness out of their dad.

But these legends, cute as they are, miss the point of Archie’s triumph: his true legacy comes from turning his father’s best-known maxim against him. If you want to win against the most powerful man in the world, speak softly and carry a big stick—or a small tree.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook