Found: Pollen on a 99-Million-Year-Old Beetle, in Amber

The pollen-dusted beetle pushes back the earliest evidence of insect-flower pollination by 50 million years.

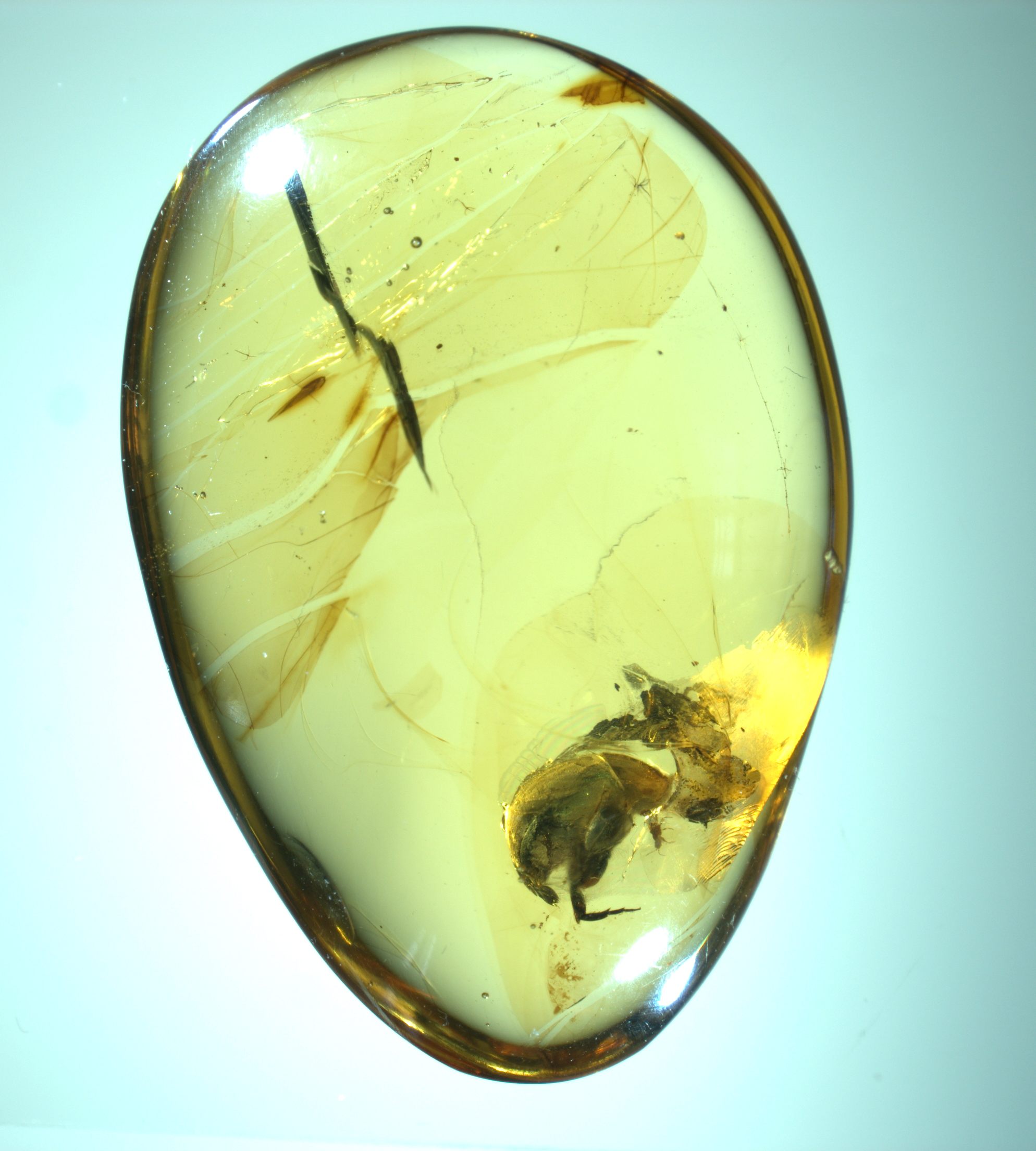

In 2017, a graduate student named Tong Bao polished hundreds of amber droplets, looking for tumbling flower beetles that had been frozen in time for tens of millions of years. Bao was writing his thesis on the beetles, and had come to the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology (NIGPAS) to see whether any had been trapped in the institute’s trove of Burmese amber. He polished every cloudy, fossilized lump, held it up to the light, and placed each beetled piece in a small pile. After polishing one amber fragment, Bao spotted something unusual: Pollen grains were sprinkled across a beetle’s legs like powdered sugar.

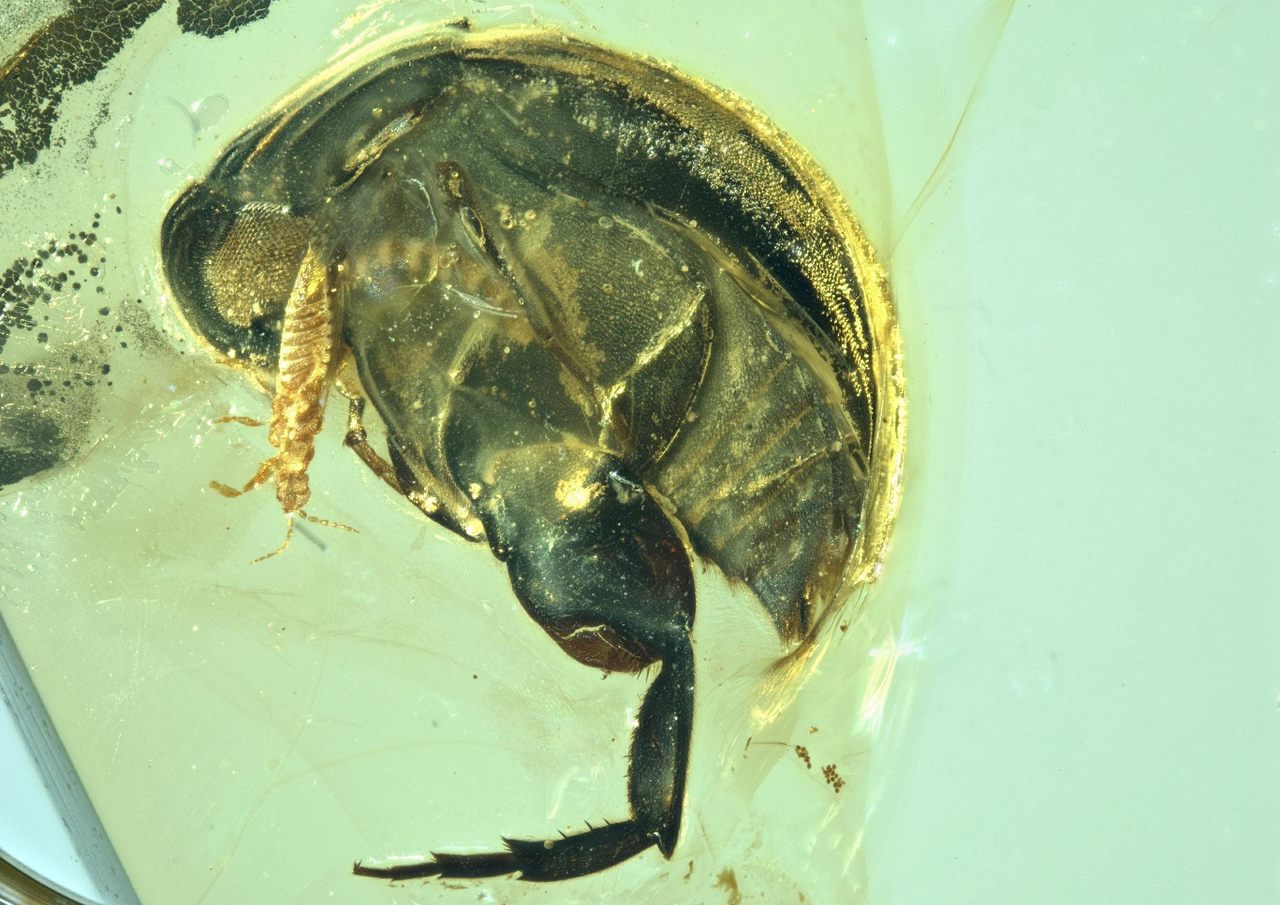

This ancient tumbling flower beetle, approximately the size of a pea and immortalized in tree resin 99 million years ago, represents the earliest evidence yet of insects pollinating angiosperms, or flowering plants, according to a study recently published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. It is twice as old as the oldest-known specimen of its kind: The finding pushes back the timeline of insect-angiosperm pollination by a whopping 50 million years.

“What is so very important about this fossil is that flowering plants established what’s called co-evolution,” says David Dilcher, a professor emeritus at the Indiana University and an author of the study. “It’s why flowers want to be beautiful, to be fragrant, and to give rewards and nectar to the animals that come visit them.” Researchers have long believed that insect pollination was responsible for the mysterious appearance and efflorescence of flowering plants in the Cretaceous period, which Darwin once called “the abominable mystery.” This discovery offers tangible proof.

Amber preserves life on contact. The tree resin drips into soft tissues and hardens into a protective shell that can retain details on a cellular level. As a result, the beetle’s level of preservation is extraordinary. Dilcher and Bo Wang, a paleontologist at NIGPAS who supervised Bao’s thesis project co-authored the paper, counted 62 visible grains of pollen clinging to the beetle’s body hair on its left side (the beetle’s right side was obscured in a fizz of microbubbles). “You could immediately see the little dustings,” Dilcher says. Though the grains look like specks to the naked eye, a microscopic view revealed three distinct grooves on each grain, suggesting they came from a eudicot group of flowering plants. (The grooves also ruled out the possibility that the specks were ancient freckles of fossilized dung, the researchers write.)

The researchers were unable to identify the specific species of plant, but whatever flower species fed the bee is certainly extinct now, Dilcher says. Modern eudicots are the largest group of flowering plants, including oaks, poppies, and buttercups. “They’re out saying, ‘Hey, I’m beautiful! I smell good! Come visit me!” Dilcher says. “And the beetle did.” The beetle was likely drinking nectar or eating pollen when it met its untimely end, Dilcher says—a good way to go.

Before Bao polished the amber, it sat on a shelf for five years, assumed to be just another fossilized tumbling flower beetle, Wang writes in an email. “We could not see the beetle clearly, let alone the pollen,” he says. Wang first collected the specimen in 2012, at a sprawling amber bazaar in Tengchong, a city near China’s border with Myanmar, also known as Burma. Tengchong is known as the best city in the world to buy Burmese amber; Wang bought several hundred pieces, including the beetle, from a Burmese friend.

More recently, some researchers have stopped acquiring amber from Myanmar, Katharine Gammon reports for The Atlantic. Burmese amber is a paleontological goldmine, but it can also be an ethical minefield, as Joshua Sokol reported for Science magazine in 2018. The fossils come from Kachin, in northern Myanmar, and since 2017, the amber mines have helped to fund a civil war that the UN has described as genocide. The mines themselves are narrow, dangerous passageways winding hundreds of feet into the earth, and some contain land mines. Elephants carry the specimens from the mines to markets in China.

Even if scientists stop acquiring new amber from the mines, their current trove of specimens still holds undiscovered information about life from nearly 100 million years ago, when the first flowers bloomed. Wang and his collaborators plan to continue investigating the relationship between angiosperms and insects found in his collection of amber, which currently sits in NIGPAS, waiting to be polished.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook